The Devil’s Treasure: A Book of Stories and Dreams

by Mary Gaitskill

McNally Editions, 288 pages, $18

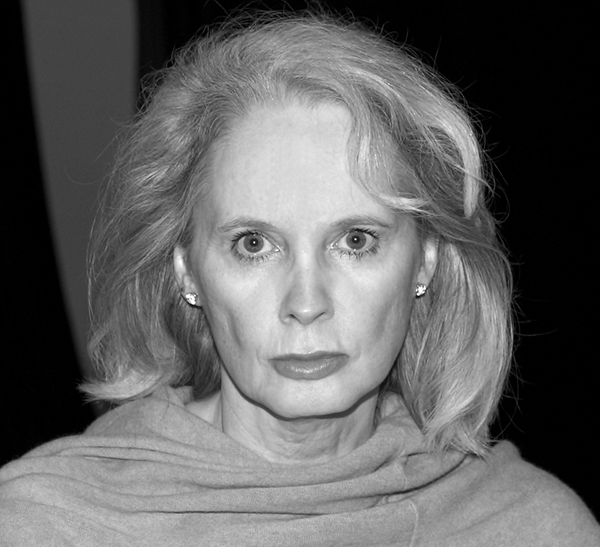

The writer Mary Gaitskill’s latest book, The Devil’s Treasure: A Book of Stories and Dreams, was republished this month by McNally Editions, which for almost two years now has been reissuing books that have been overlooked. Gaitskill is an era-defining talent, one of the best American fiction writers working today, and the book is a collage of fiction, autobiography, and fairy tale that seeks, through “ordered disorder,” to approach a fundamental thing about making art—one that defines Gaitskill’s oeuvre.

To get at this elusive but essential quality, the book starts with the fairy tale that frames the other sections, in which a little girl named Ginger (also the name of the protagonist of Gaitskill’s most recent novel, The Mare) goes down to hell to “steal the devil’s treasure.” Ginger learns that she is safer if she doesn’t stop to look too closely at the goings-on of the underworld. Gaitskill follows this with a direct first-person comment in her own voice: “Oh, but I stopped to look. I always stop to look. And I often write what I see, or I try.”

“Some of her truths flout orthodoxy.”

The Devil’s Treasure was originally published in 2021 as an art-book by Ze, a small publisher run by one of Gaitskill’s friends. Since its release, Gaitskill has become a Substacker, discussing many of the things she sees more directly. She has emerged as one of the few big-name literary writers willing to discuss the topics of the new orthodoxy in their complexity—sexual assault, writing across race—despite, as she has written, being mostly on the side of the orthodoxy’s proponents. This is significant, because she is an establishment figure, widely respected by her peers, who in many ways has been a progenitor of today’s ideas. Sexual violence has been a perennial topic for her, and much of her work’s subtext is about trauma, recovery, and dignity for victims. However, the method of her genius has always been radical truth-telling. And some of her truths flout orthodoxy. She has said, for example, that rape is about sex and power, and that false accusations do happen. She has confessed that, as a young woman, she herself lodged such a false accusation, and that the feelings she was expressing then are relevant to today’s debate. All of this is obviously true, but these are claims that most public intellectuals in Gaitskill’s world would be afraid to touch.