American trust in media is at an all-time low, so it couldn’t be more appropriate that Honore de Balzac’s Lost Illusions—a novel brimming with contempt for the rising bourgeois free press—has been adapted into an elegant epic of a period film. Directed by Xavier Giannoli, Lost Illusions stars Benjamin Voisin as Balzac’s infamous protagonist Lucien de Rubempré, a young poet who moves to Paris with an older society woman, Mme. de Bargeton (Cécile de France), only to be discarded by her and forced to fend for himself—which he does brilliantly, at least for a while.

The opening lines of the film state, “This is a tragedy”; it doesn’t end well for young Lucien. Taking a job as a hack at a liberal paper, he writes under his mother’s aristocratic maiden name, de Rubempre, rather than the common name he inherited from his father. His quest for easy fame and an official grant of nobility leads him to betray his friends and his artistic principles, only to end up broken and destroyed.

“No one on the left better described the capitalist contradictions of contemporary society.”

Despite the period setting, the film is haunted by the ghosts of the temporal now. “News, debate, and ideas had become goods,” says the narrator of the film, the royalist novelist Raoul Nathan. “Money was the new royalty, and nobody would chop off its head.” Nathan functions as a kind of stand-in for Balzac himself, portrayed by the actor and former teenage filmmaking wunderkind Xavier Dolan.

Balzac’s obsessively detailed literary excavations of bourgeois society aren’t the kind of thing I typically find appealing. I am usually turned off by writers and artists who are so tethered to the material world—to reality. I love Burroughs, Beckett, Ballard, Murakami, and other writers who indulge the fantasy space, the weird, and the eerie in their assessments of the modern condition. Even so, Balzac defined a certain literary and political stance that contributed to the development of a cultural current that fascinates and allures me: the reactionary right-wing avant-garde.

Balzac’s visceral disgust for the rising bourgeois liberalism of 19th-century France opened the same aesthetic and philosophical door that Celiné, Wyndham Lewis, Pierre Drieu la Rochelle, Yukio Mishima, and Michel Houellebecq (our greatest living literary artist) would also walk through. Though these figures come from different times and nations, they are united by their revulsion toward liberalism that nevertheless clashes with the political and economic critiques of liberalism offered by Marxists.

These writers are less concerned with the antagonism between capital and labor than they are with the erosion—or what Marx would have called the “liquidation”—of social structures and traditions, the rewarding of greedy and conformist mediocrities, and the undoing of the nation under liberalism. It is a literature less about diagnosing the problems in the world and advocating for its progress than it is about bemoaning and mourning a society that has already fallen. Even at its most realistic, it is inherently what Derrida would have called a hauntological literature, because it grieves the loss of a culture that will never come back and, perhaps, never truly existed.

Balzac was a monarchist who longed for the full restoration of the hereditary rights of the aristocracy. He was also, however, an artist first and foremost and would rarely indulge in the kind of open political advocacy practiced by mere ideologues. This all engendered in Balzac a well-considered rejection of the rise of liberalism. Where others were dazzled by the fervor of revolution and the innovations of bourgeois society, Balzac saw death. The desire for greatness and beauty was replaced with the pursuit of success and financial standing, leading to the end of a culture and the birth of a cult of the self.

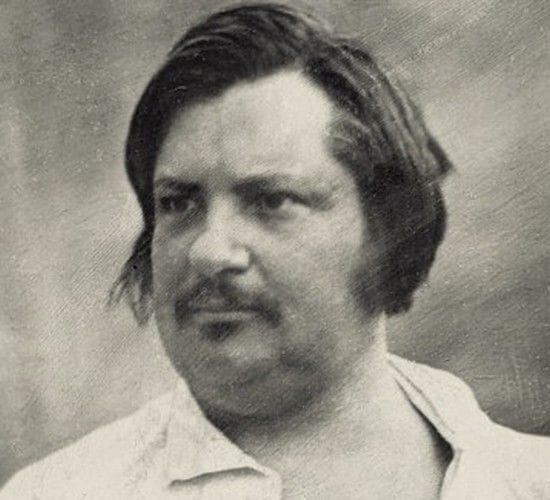

Peering through the facades of the age, moving easily between classes, Balzac revealed Paris as a labyrinth of ideology and political-economic contradiction. No one on the left better described the capitalist contradictions of contemporary society. “Balzac was politically a legitimist,” Engels wrote. “His great work is a constant elegy on the inevitable decay of good society, his sympathies are all with the class doomed to extinction.” And yet Engels declared Balzac “a far greater master of realism than all the Zolas passés, présents, et a venir [past, present, and future].” Marx likewise praised Balzac’s “profound grasp of real conditions.”

Marx’s and Engels’s appreciation for Balzac presages a common trend in communist literary theory: In matters related to the accurate assessment of class society and its contradictions, the scornful realism of the reactionary rightist is always preferable to the delusional utopianism of the idealist leftist. Certainly, Ezra Pound understood the relationship between finance capitalism and modern war better than did someone like Andre Bréton, forever confused by his own misguided attempt to reconcile the surrealist ethos with a Marxist critique of capital. Ask yourself this: Is any literary artist on the left more capable of cutting through to the heart of the alienation and profound loneliness of the contemporary than Houellebecq? I don’t think so.

Balzac’s work is a sociological document as vivid and fleshed out as the social photography of August Sander in early 20th-century Germany. But it functions equally as Shakespearean tragedy, with all of French society standing in for Hamlet or Othello. He saw that art wasn’t being liberated by liberalism so much as it was being neutered and funneled into the schizoid logic of capital itself. Under feudalism, aristocrats would finance art with no immediate reference to what would prove popular. But under liberalism, Balzac bemoaned the tendency of artists to shill their work to the masses, reducing the quest for greatness and timelessness to a grubby grasping for status within the new class society. Passion, impossible to quantify, had been vanquished by ambition. “Passion is universal humanity,” wrote Balzac. “Without it, religion, history, romance, and art would be useless.” And passion can’t thrive in a society with a newly minted owning class and petty bourgeois clawing each other’s eyeballs over slices of the newly available pie.

Lost Illusions is the work that best encapsulates Balzac’s grief over the slow death of art. Its title refers to that very phenomenon; Lucien begins the novel having deep, intense conversations with his closest friend about the necessity of art and its revelations of truth and beauty. But in his obsession with the attainment of status in the new Parisian society, he abandons his principles: first joining a liberal tabloid press, writing hit pieces that earn him fame, then abandoning his apparent convictions to join a royalist paper, hoping it earns him a royal grant of title and financial legacy. Balzac’s brutality is unsparing. For all of Lucien’s fame-whoring, he fails to gain what he wants. Instead, he ends up with nothing, back in the province where he grew up. Balzac knew that just because liberalism promised “opportunity” to all didn’t mean it made good on that promise.

And yet I couldn’t help feeling a faint glimmer of hope watching Giannoli’s adaptation of Lost Illusions. The society it depicts, a rising industrial bourgeois society with artists competing for money and fame by winning the attention of a broad public, is as dead as the feudalist one that Balzac mourned for. Artists, the real ones still among us anyways, know very well that they won’t make any money. But they keep making it anyway. Filmmakers such as Gaspar Noé lose money on almost every project and routinely find enthusiastic backers to finance their work at a loss anyways. Art is once again moving away from the masses, and artists are working for smaller audiences. Maybe as the system Balzac described breaks down, artists will look away from the mass market and toward a more select group of patrons. Or perhaps Balzac would shake his head at my lingering idealism.