In late March, Volodymyr Omelyan, the former Ukrainian minister of infrastructure, went on NPR to denounce a “clash of civilizations” now underway. On one side, as Omelyan saw it, was Ukraine, which only wants “democracy,” “progress” and “development.” On the other was Russia, which wants “to occupy, to destroy, and to kill.”

What Omelyan is describing is a clash of Good and Evil. Whether you think of the Russia-Ukraine conflict this way depends on which side you are on. But whatever you call it, it isn’t a clash of civilizations. In fact, it is almost the opposite of what the late Harvard political scientist Samuel Huntington meant when he brought the phrase “clash of civilizations” into common parlance with an article in Foreign Affairs in 1993.

Huntington’s aim was to complicate our understanding of the world, not to simplify it. The ideological struggles that had pitted Communists against anti-Communists for 75 years were on their way out. The new struggles, he wrote, would pit seven or eight cultural areas against one another: “Western, Confucian, Japanese, Islamic, Hindu, Slavic-Orthodox, Latin American, and possibly African.” Huntington spent the years until his death in 2008 as a partisan in these struggles, urging the United States to recognize—and safeguard—the “Anglo-Protestant” cultural traits that had given America the upper hand.

The clash-of-civilizations model proved spectacularly useful for making predictions. Huntington produced a detailed map of one civilizational border that seemed to explain everything: the line where Western Christianity met the Orthodox and Muslim worlds 500 years ago, on the eve of the Reformation. In 1993, that line was a battle line, as post-Communist Yugoslavia collapsed. It is a battle line today: Follow it north, and you will pass through the middle of Ukraine.

One set of frontiers drew Huntington’s particular attention. “Islam has bloody borders,” he wrote. Whole academic departments have been founded to denounce that sentiment, but who could refute it? It explained the conflict between Azerbaijan and Armenia over the Nagorno-Karabakh region, the destruction of the Ayodhya mosque in Uttar Pradesh, the repression of the Uighurs. Huntington was among the first Western scholars to anticipate a “Hinduization” of India, and to predict that China, through the sinews of its mercantile diaspora, would soon dwarf Japan as an economic influence in Asia.

"Ideology has returned to the fore.”

The clash-of-civilizations theory is brilliant and enduringly useful. But to listen to commentary on the Russo-Ukrainian war is to realize that many important political actors haven’t the foggiest idea what it actually means.

Granted, it has its paradoxes. While all civilizations go through cycles of quiescence and belligerence, these are frequently determined by non-civilizational factors, especially demographics. Pious, purity-obsessed Islam was the clashing civilization par excellence at the turn of this century, and almost all the claims of its political radicals were made in civilizational terms. But a big part of the problem, as Huntington saw clearly at the time, was a population explosion that had been going on for a generation. The Arab world had produced a glut of military-age sons, and offered them precious few avenues to wealth and social standing. Some sought glory as mujahideen or suicide bombers.

The shrewd sociologist Gunnar Heinsohn went further. He speculated that Islamic fundamentalism, while sincerely asserted, might be a red herring. The residents of the Palestinian territories, for instance, were not the most religious people in Muslim lands. But in barely a generation after 1967, the population of the West Bank and Gaza bulged to 3.3 million, from 450,000. Bombings proliferated. When this wave of men passed from youth into sedentary middle age, however, the problem of terrorism mostly passed with them.

By the middle of this century, the population of Africa will double, adding roughly 1.2 billion young people to a straitened economy. Heinsohn and Huntington would predict violence as a result. When it comes, grandiose civilizational claims will be made by those who commit it. But that will not mean it has a wholly civilizational cause.

What is unfamiliar, in Huntingtonian terms, about the Russia-Ukraine conflict is that it is being fought by two countries that are demographically stagnant. Aggression has not resulted from the friction of two over-dynamic and overpopulated civilizations, but has been drawn into a civilizational vacuum.

Huntington had a traditional idea of what a civilization is and how to maintain one: by protecting its borders, its language, and its social structure. But over the past generation, not a single effective US president has agreed. Washington has aggressively policed the international order it established at the end of the Cold War. But this order treats civilizations as if they are vulgar, not to be spoken of—you might even say uncivilized. Maybe America’s deep liberal roots led it to see most civilizational institutions as constraints, as insults to the idea that all men are created equal, as obstacles to human flourishing. Maybe the more recent American commitment to civil rights—which brings an instinct for backing underdogs—was misapplied in other, foreign contexts.

For whatever reason, the United States frequently sides with the more civilizationally distant of two warring civilizations: with the colonial world against Europe in the late 1940s, with Egypt against France and Britain in 1956, with Pakistan against India in 1971. It sides with its enemies against its rivals. In the Balkans in 1998, it rallied along with various jihadists to back Kosovo against Serbia, an episode that left an enduring mark on Russian attitudes towards the West. The immediate reaction of George W. Bush to the 9/11 attacks was to declare: “Islam is peace.” For a considerable number of people inside and outside our civilization, the result has been confusion.

Huntington paid especially close attention to the rivalry between post-Cold War Russia and post-Cold War Ukraine. He noted the Crimean parliament’s 1992 declaration of independence from Ukraine, and speculated that Ukraine might split politically into Russian and non-Russian halves. They had plenty to fight over: Crimea, the Soviet Union’s Black Sea fleet, and nuclear weapons. But this was a rare instance when Huntington explicitly ruled out a clash of civilizations. “If civilization is what counts,” he wrote, “the likelihood of violence between Ukrainians and Russians should be low. They are two Slavic, primarily Orthodox peoples who have had close relationships with each other for centuries.” Huntington called this “civilizational rallying” and suggested that the West could use it “to promote and maintain cooperative relations with Russia and Japan.

One might think that harmonizing the constituent parts of European civilization would have grown easier with time. Both the Eastern Orthodox and Western Catholic-Protestant parts of Western civilization have fallen into the demographic doldrums. Both inhabit a global economy. Both use English as a lingua franca.

In certain respects the two sides in the Cold War actually appear to have reversed roles. The Russian Orthodox patriarch Kirill gave a sermon in early March in which he questioned the values of the coalition opposing the Russian invasion of Ukraine: “In order to join the club of those countries,” he said, “you have to have a gay pride parade.” This is the tone of mainstream American anti-Communism of the 1960s, mocked by Richard Hofstadter and Stanley Kubrick then as Kirill is mocked on social media now. Those Americans who lament woke capitalism, meanwhile, are echoing not Saul Bellow’s complaints about ideologues undermining cultural institutions, but Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn’s complaints about ideologues running cultural institutions.

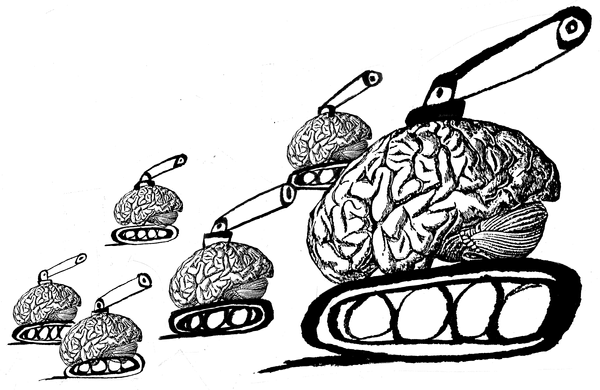

Why do people mistake the current war for a “clash of civilizations”? Huntington was right that battles over ideology were giving way to battles over civilization. But a generation later, ideology has returned to the fore. Attempts to settle on a name for this ideology—from “neoliberalism” to “global capitalism” to “wokeness”—may not have met with much success, but 21st-century certitudes have split the world in two, just as Communism once did.

In the 1990s, Huntington developed another analytic tool, one that may be even more useful to us than that of civilizational clashes. He wrote of “torn countries.” A torn country is one in which a wised-up elite can benefit from globalization, but in which the non-elite parts of the country may pay a price in disruption and insecurity. On the eve of NAFTA, Mexico struck Huntington as the “torn country” with the most reason for optimism. It had elites eager to join the hegemonic civilization, common people ready to cut them some slack as they did so, and a welcome extended by the hegemonic civilization itself. Russia, as Huntington saw it, had none of those things. It was a torn country in trouble.

Over a generation of globalization, Russia’s problems as a “torn country” deepened—to calamitous effect, as we can now see. It may be even more troubling that, over the same period, the countries of the West have all, in their own way, become torn countries, too.