Liberalism is elitist, imperialist, and anti-democratic. These claims are now frequently made by critics of liberalism, and rejected by its defenders. Despite the intense disagreements between these two camps, both affirm that broad political participation is to be praised, and imperial rule should be deplored. Understandably, then, liberalism’s defenders have recently made a cottage industry out of warnings that liberalism is the only acceptable ideology for those who wish to “defend democracy.” Yet liberalism’s monolithic self-positioning on the side of democracy and anti-imperialism is a fairly recent development. In an earlier era many liberals accepted the claims now made by liberalism’s opponents—that it empowers elites, suppresses the popular will, and licenses imperial rule—while insisting that these are good things. No one expressed this view more cogently than James Fitzjames Stephen, the Victorian jurist whose writings contain much to unsettle critics and defenders of the liberal creed.

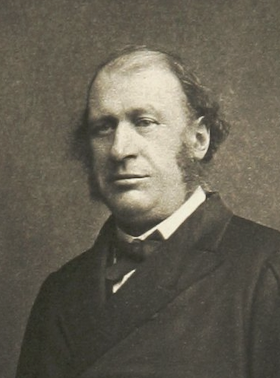

In 1829, James Fitzjames Stephen was born into the world’s most liberal nation and most powerful empire. He came from an impressive branch of what social historians have dubbed “the intellectual aristocracy” of Victorian England, the stratum of interrelated members of the knowledge classes, who gave direction to the society’s morality, literature, and policy. His family had deep roots in the antislavery and evangelical movements, and his forebears had considerable achievements in politics and the press. His father, in addition to being a prolific writer, had cut so important a figure in the administrative state that he earned the moniker “Over-Secretary of the Colonies” (a play on his official title, colonial under-secretary); among other feats, he drafted the bill to end slavery in the colonies, and did much to develop the legal framework for colonial self-government. Fitzjames’s brother Leslie would become an influential historian and literary critic, and Leslie’s daughter (Fitzjames’s niece) was none other than Virginia Woolf.

Fitzjames himself had a notable legal career, from which he finally retired as a High Court judge. Most important, he would serve a stint as “legislator for the Subcontinent” (officially, law member of the Council of the Viceroy of India) from 1869 to 1872. In a short time, Stephen remade considerable portions of Indian law. This experience deepened his impatience with parliamentary government. It was, for instance, a standing source of frustration to him that India benefited from a more “rational” legal system than his homeland, since his projects for codifying parts of English common law met with failure in the House of Commons. His experience in India crystallized his contempt for the “sentimentalism” that he believed was rendering his countrymen incapable of facing hard truths. Indeed, he once informed a devoutly Christian correspondent that his time in India had made him sympathize with Pontius Pilate, who had been just like him: a “government house” apparatchik stationed in a backward land, doing his best as the emissary of a superior polity in the face of widespread poverty and strange religious movements.

Stephen is best known today as an adversary of John Stuart Mill. Stephen’s most widely read work of political thought, 1873’s Liberty, Equality, Fraternity, attacked England’s then-most famous philosopher. (One wag thought the critique so successful that he joked that it had killed Mill, who had in fact died from natural causes shortly after the book appeared.) Because of these criticisms, some scholars have placed Stephen in the conservative canon, but this classification is misleading. Stephen held partisan Conservatism in contempt, and rejected many of the beliefs associated with Edmund Burke. For example, he didn’t see prejudice as a source of embedded wisdom and set no store by tradition and inherited customs as such; he didn’t cherish the landed nobility as a specially beneficent class; he was ambivalent about the political effects of organized religion, and by the end of his life was openly skeptical of the social-moral value of Christianity; and he was favorable to the French Revolution on the grounds that the ancien régime had oppressed all but the “privileged classes.” (Like many in his day and since, he regarded the upheavals of 1789 as issuing from long-standing injustices against the bulk of the population, but spurned “Liberty, Equality, Fraternity” and “the Rights of Man” as senseless tenets of a pseudo-religious faith inconsistent with the good working order of society).

“Stephen … sought to subject politics to the cold light of critical reason.”

The emphasis on the nonrational sources of allegiance, the desire to sanctify civil society, to guard an aesthetic attachment grounded in the “loveliness of the country” and an esteem for persons who could “embody … institutions, so as to create in us love, veneration, admiration” that Burke made central to his picture of a “gentlemanly” and “chivalrous” aristocratic order—all of this was dismissed by Stephen, who sought to subject politics to the cold light of critical reason. In this, his master was Jeremy Bentham, the eccentric and curmudgeonly philosopher-reformer who had sought to amend every aspect of social life in accordance with the standard of utility. Indeed, Stephen thought of himself as a defender of a hard “old utilitarian” point of view against the indulgent and emotional movements that were gaining steam in his time. He exhibited the self-confident ratiocination of the professional and administrator, not the reverent regard for a consecrated order of the temperamental conservative.

Indeed, Stephen maintained that on the live questions of the epoch, he objected not to “the practice of modern Liberals” but to the intuitions and impulses of an increasingly influential extreme of the Liberal coalition. In the same year he launched his withering critique of Mill, he stood (unsuccessfully) for Parliament—as a Liberal. Later in life, particularly after parliamentary Liberals, led by their great leader William Gladstone, committed to home rule for Ireland, he dissociated from the party. But Stephen conceived of this distancing in terms of staying true to the liberalism of his salad days—he hadn’t changed, but the Liberal party had been taken over by “Jacobins” and “socialists.” By the time of his death in 1894, his pessimism about the prospects for British political culture had become overwhelming.

For Stephen, as his French translator put it, had a “very liberal mind … possessed of modern ideas” but recoiled at the “difficulty and danger” of attempts at “unlimited and absolute extension of the ideas of ‘liberty, equality, fraternity.’” Stephen’s liberalism involved such specific articles as the protection of private property, rationalization of the legal-administrative system, free trade, and equality before the law (which in his and many contemporaneous liberals’ eyes implied nothing about equal votes). But it was also, more generally, a commitment to the application of reason to politics for the sake of moderate reform—and, as a result, to the leadership of the social group that was most reasonable: namely, knowledge-workers and professionals—his own sort. “Those only are entitled to the name of liberals,” he wrote, “who recognize the claims of thought and learning, and of those enlarged views of men and institutions which are derived from them, to a permanent preponderating influence in all the great affairs of life.”

Though the word wouldn’t be coined until several decades after Stephen’s death, his ideal was a kind of technocracy. Unlike many of today’s liberals, he accepted without compunction the inegalitarian implications of his beliefs. A worrisome aspect of Victorian civic attitudes, he claimed, was the underrating of expertise: “The work of governing a great nation … requires an immense amount of special knowledge and the steady, restrained, and calm exertion of a great variety of the very best talents.” His was thus the age for “engineers, men of science, lawyers, and the like.” Only by better incorporating into statecraft the intellectual habits and virtues of the professions could politics be redeemed from its “perfectly disgusting” condition.

Stephen’s elitism was aimed at two principal sets of enemies. The first, and most obvious, were democratizers. He insisted on the incapacity—intellectual and moral—of the masses for political rights. Victorian England was hardly a democracy in Stephen’s formative years, and even after the successive expansions of the franchise in 1867 and 1884, it was still far from universal suffrage. But Stephen’s outlook was dour. He held the view that democracy’s arrival might well be inevitable. Yet he was determined to fight: “The waters [of democracy] are out but I do not see why as we go with the stream we need sing Hallelujah to the river god.”

Since it was evident that “the minority are wise and the majority foolish,” the only fit conclusion was that “the wise minority are the rightful masters of the foolish majority.” Democracy effaced the distinction “between wisdom and folly.” It rested on the presumption that “mediocrity,” “impudence,” and “rudeness” were entitled to a say in public affairs equal to that of intellect and expertise. Democracy had nothing to do with liberalism properly understood, which was about finding a way for reason to set the direction of government against ignorance, passion, habit, and custom. Stephen’s friend and predecessor as legislator for India, another liberal anti-democrat named Henry Maine, encapsulated their case: “Democracy would result in a dead level of ultra-conservatism,” for “the establishment of the masses in power is of blackest omen for all legislation founded on scientific opinion.”

“Coercion was an instrument for improving humanity no more suspect than any other.”

Stephen’s technocratic liberalism had another enemy: libertarianism (like technocracy, the word itself is a 20th-century coinage). For his elitism comprised a defense not only of the officialdom of learned experts, but also of “powerful and well-organized” government. Stephen’s apologias for a strong state ran up against, as he saw it, an expanding section of the intelligentsia that had erected for itself a “religious dogma of liberty.” Stephen was contemptuous of “the great mass of speculative men” who “set themselves either to challenge the right of Government to meddle with anything but police subjects, or to prove that in point of fact they can never do so with advantage.” (Only police subjects is a pithy summation of the “nightwatchman state” that libertarians would champion a century later.) These thinkers would leave “everyone indiscriminately … to do what he likes.” This outlook, Fitzjames wrote, amounted to “a mean and cowardly” abdication of the elite’s duty to the populace. The leaders of a society were not to allow each man to go astray as he willed, but instead to steer him in the right direction. “Wise and good men ought to rule those who are foolish and bad,” Stephen concluded. Nor should the elite be bashful about the need for force in setting the country’s trajectory. Coercion was an instrument for improving humanity no more suspect than any other; all that mattered was that it be exercised efficaciously and that one “direct it aright.”

Stephen believed Mill had offered aid and comfort to a pathological libertarian streak in the national culture. In terms of policy, Mill wasn’t a libertarian. But Stephen thought Mill avoided being so only by ignoring the clear implications of his theory. For Mill’s On Liberty, which was nothing less than a “gospel” to many Victorian readers, famously defended the “very simple principle” that society was justified in interfering with individuals only to prevent harm to others. But state action, even of the most anodyne sort like repairing infrastructure, was funded by taxes. And was not taxation interference—indeed, interference often of an invasive and intimately felt form? “To force an unwilling person to contribute to the support of the British Museum is as distinct a violation of Mr. Mill’s principle as religious persecution,” Stephen argued. “The difference between paying a single shilling of public money to a single school in which any opinion is taught of which any single taxpayer disapproves, and the maintenance of the Spanish Inquisition, is a question of degree.” Consequently, On Liberty fed into an “attack on all government whatever.” What many still regard as a sacred text of liberalism was to Stephen a recipe for anarchy.

Unsurprisingly given these proclamations, Stephen’s favorite philosopher was Thomas Hobbes, the great 17th-century theorist of absolute sovereignty and the ineluctability of coercion. Equally unsurprisingly, Stephen was impatient with the utopian schemes prevalent in the literature of his own era, which foretold the withering away of the state and disappearance of coercive power. Against “the infantine satisfaction with things as they are going to be,” Stephen enunciated something like a law of the conservation of coercion. The historical record, he argued, revealed no decline in the relevance of coercion to political life, nor did it support the thesis that coercion was more necessary to “backward states of society” (as Mill called them) than to advanced ones. “President Lincoln attained his objects by the use of a degree of force which would have crushed Charlemagne and his paladins and peers like so many eggshells.” No great improvement—the spread of Christianity, the Reformation, and the French Revolution were some on which Stephen dwelt—had been accomplished and consolidated without enormous force.

Today, especially for Americans, liberalism is associated with the separation of church and state. But in mid-19th-century Britain, liberalism was divided on this subject, and Stephen sided with those who defended church establishments. Indeed, he remained an establishmentarian even as his personal faith eroded, so high a value did he place on the visible way in which the existence of a state church sent the message that there was no fixed limit to vigorous government action. A religious establishment was a potent symbol that, as Burke had put it, “the state ought not to be considered as nothing better than a partnership agreement in a trade of pepper and coffee, calico or tobacco, or some other such low concern,” but was rather “a partnership in every virtue and in all perfection.” Or in Stephen’s pungent prose:

The division between Church and State, the maxim of a free Church in a free State, will mean that men in their political capacity are to have no opinions upon the topics which interest them most deeply; and, on the other hand, that men of a speculative turn are never to try to reduce their speculations to practice on a large scale, by making or attempting to make them the basis of legislation.

Should the principle of separation take root, he warned, “the State will be degraded, and reduced to mere police functions.” Making matters worse, a state so degraded would leave individuals prey to the illiberal pressures that powerful associations could exert. By attacking the state and diminishing its range of activity, misguided liberals softened the ground for their enemies:

Associations of various kinds will take its place and push it on one side, and completely new forms of society may be the result. Mormonism is one illustration of this, but the strong tendency which has shown itself on many occasions both in France and America on the part of enthusiastic persons to ‘try experiments in living,’ by erecting some entirely new form of society, has supplied many minor illustrations of the same principle. St. Simonianism, families of love by whatever name they are called, are straws showing the set of a wind which some day or other might take rank among the fiercest of storms. Such experiments as these have nothing whatever to do with liberty. They are embryo governments, little States which in course of time may well come to be dangerous antagonists of the old one.

If radicals assailed the prerogatives of government for the sake of staying “neutral” on the greatest questions and thereby expanding citizens’ liberty, the vacuum would be filled by private organizations that were not chary about pushing a positive moral vision, even if by means of intimidation and oppression. What was needed, instead, was for the best and the brightest to own up to the fact that it was “simply impossible that legislation should be really neutral” and to admit that “governments ought to take the responsibility of acting upon such principles, religious, political, and moral, as they may from time to time regard as most likely to be true,” with all the grave moral burden that this entailed.

The only route to any liberty worth speaking of—let alone to more primordial goods like order and public safety—involved ignoring the freedom-fanatics whose proposals would result in private entities crowding out the government altogether and cowing citizens in their turn. Like all other social goods, any liberty that merited the name was “dependent upon a powerful, well-organized, and intelligent government.” Educated men directing the apparatus of coercion according to the best evidence and with the insight of specialists: Anything other than this was at best reactionary idiocy and at worst the return of the state of nature.

Stephen was unabashed about connecting his ideal of strong technocracy to imperial rule. His commitment to the British Empire he had served so devotedly hardened his opposition to libertarians and democratizers for two reasons.

“Stephen was unabashed about connecting his ideal of strong technocracy to imperial rule.”

First, those who supported empire abroad and “liberty, equality, and fraternity” at home had to give an account of why the two spheres, imperial and domestic, should be regulated according to such different principles. The approach commonly taken, including by Mill himself, was to delineate a threshold of societal development, above which coercion only to prevent the individual from harming others was admissible, but below which “civilizing” despotism by a foreign power of greater enlightenment was appropriate. “Primitive” peoples unfit for public deliberation and coherent collective action fell below the line, but advanced societies such as Britain were above it.

Stephen rejected this attempt to draw a boundary between the faraway lands of the empire, on the one hand, and the metropole and places like it, on the other. If it was right for the British, being more highly developed, to rule over “the Hindoos, why then may not educated men coerce the ignorant [at home]? What is there in the character of a very commonplace ignorant peasant or petty shopkeeper in these days which makes him a less fit subject for coercion on Mr. Mill’s principle?” So long as the upper classes remained wiser than the general population, the British Constitution ought to approximate the imperial government of India. An assertive technocracy was a kind of domestic imperialism, and was justified because of that similarity. Imperialists who were democratizers or libertarians in the mother country were thus engaged in an incoherent enterprise. They were cutting the rug out from under their nation’s greatest glory and most beneficent enterprise, its empire, for there was no way to embrace the revolutionary credo at home without it spreading beyond the British Isles.

Stephen’s anti-democratic and pro-imperial tendencies were joined in another way. For part and parcel of the demos’s political incapacity was that it couldn’t appreciate the imperial project. Lacking material security, shortsighted, concerned only with what would benefit them directly and in the near term, they would unwind the empire. To appreciate how the imperial project contributed to Britain’s reputation and security, or how it elevated those under its rule, was outside the grasp of a democratic electorate. “Anything like an adequate conception” of the empire and “the great part which England has to play in the world” was beyond the intellectual reach of the workers and petty bourgeoisie whom democracy would make the predominant political force. These demographics would see governing India “firmly and wisely” merely as a drain on their pocketbooks; their “mean, illiberal” outlook didn’t permit them to care about expanding the welfare of strange-seeming peoples halfway around the world.

Stephen was concerned that the populace would overturn the liberal imperial order that was, he was certain, improving the life chances of millions and extending law and justice to benighted regions. Similar worries are heard today from “democracy’s defenders.”

Stephen’s championing of self-assured expert rule, a powerful state, and an imperial foreign policy reads like an exaggerated version of the contemporary conservative’s lament at what 21st-century liberalism has become. In one way, though, Stephen departed decisively from today’s liberal script. For Stephen was, in practice, a champion of free speech and privacy. Although he found the way Mill theorized these values incoherent and implausible, Stephen accepted a very wide conception of freedom of discussion, and he demanded forbearance from meddling in private life. Mill’s distinction between self- and other-regarding actions was tendentious (a mere philosophical version of today’s browbeating slogans, “How does this affect you? Why do you even care?”) and insufficient to ground the protection of privacy. The real reason privacy had to be respected, Stephen insisted, was rather because “no police or other public authority can be trusted with the power to intrude into private society, and to pry into private papers.”

Likewise, he defended liberty of discussion with an array of familiar rationales: It conduced to stability (“a perfectly free press is one of the greatest safeguards of peace and order”); it had epistemic advantages (“the concession of a legal right of private judgment to all mankind is highly beneficial to the interests of truth”); it contributed to the moral development of the citizen (who learned the values of “candor,” “sincerity,” and respect for the “man who publishes what he really believes to be true from a desire to benefit mankind”). Conversely, restrictions on speech “afforded a channel for the gratification of private malice” and would inevitably be applied arbitrarily.

Stephen’s liberal convictions on this subject related to another important aspect of his thought. Alongside his militant elitism ran a radical pluralism that at times sounds like the existentialism that would come in the following century: “Complete harmony is probably unattainable even by individuals,” he wrote. “We are forced to live” in “a dark night” of “uncertainty and ignorance,” and our “trial” was to make a “frank admission” of the limits of what we might know and yet still live up to our convictions. The conflicts that ran through the human heart naturally made their way into society. Stephen thus concluded that “there are and there must be struggles between creeds and political systems, just as there are struggles between different nations and classes.”

“Fraternity was not a complement to liberty, but spelled its end.”

This conflictual picture of social life was no cause for lament, in Stephen’s eyes. The end of social conflict wouldn’t lead to an idyll of civic friendship. Instead, it would be the advent of a reign of indifference and atomization, for “struggles in different shapes are inseparable from life itself as long as men are interested in each other’s proceedings.” Stephen deplored the utopian spirit underlying various ideological currents in his time, which considered conflict only as an indication of dysfunction or injustice. The depth of this sense of inevitable, and salutary, agonism made Stephen exasperated with calls for civility, mutual respect, and affection toward all fellow-citizens. Such a vision was a kind of social “Quakerism.” Where deep disagreement existed between people of sincere belief, Stephen didn’t “see how they can love each other.” For example, a priest’s love of a confirmed heretic could only be a nuisance to the latter man, for “that which the priest would regard as the heretic’s happiness, the heretic would regard as misery.” Fraternity was not a complement to liberty, but spelled its end, for one of the most important elements of the latter was the freedom to hate. As Stephen summed up his social theory, with reference back to his favorite philosopher:

When Hobbes taught that the state of nature is a state of war, he threw an unpopular truth into a shape liable to be misunderstood; but can anyone seriously doubt that war and conflict are inevitable … except at the price of evils which are even worse than war and conflict? that is to say, at the price of absolute submission to all existing institutions, good or bad, or absolute want of resistance to all proposed changes, wise or foolish. Struggles there must and always will be, unless men stick like limpets or spin like weathercocks.

There was not meant to be anything pleasant or easy about Stephen’s free-speech regime. Indeed, it required—and if it were to persist, it would succeed in molding—stout men, immune to taking offense. Real debate produced the worst kinds of hurt, and it was a testament to a kind of triumph over our own natures to be able to abide it.

Stephen never bothered to reconcile the pluralistic-agonistic and the elitist-technocratic strands of his thought. He wasn’t a systematizer, but a critic, a responder to political events and trends in the world of ideas. The most we can say is that perhaps he imagined that his robust professional technocracy would ultimately decide the law and policy of the country, but would do so while presiding over a public sphere defined by the rough clashing of views, and that this contest would elucidate facts that the elites would take into account as they ruled.

But there was a point of contact between the two sides of Stephen’s thought, which is hinted at in the reference to Hobbes quoted just above: his statism. The strong hand of the state was needed not to repress pluralism, but precisely because pluralism was ineradicable: “The great art of life lies not in avoiding these struggles, but in conducting them with as little injury as may be to the combatants.” Absent the state, our ideological quarrels would result in slaughter; the state’s purpose wasn’t to suppress these quarrels, but to ensure that they played out via dialogue, rather than bloody disorder. The state and its enlightened administrative class alone could serve as guarantor of “fair play” among ideological competitors. And only the instructed elite could be expected to understand the long-term and counterintuitive case for the benefits of toleration, which defied the untutored human inclination to persecute.

This was a statism for liberalism, and it involved not less, but more coercion to overcome the intolerance that was man’s first instinct, though this coercion took on a less visible form. A zealot torturing a nonbeliever to bring about his conversion deployed force; but far more force was involved in ensuring that, throughout an entire country, no zealot could get away with such activities. Much like the mission civilisatrice conception of imperialism, the free-speech state was one that didn’t scruple to shape citizens in light of a higher vision and to do so against many of the deepest habits and impulses of humanity.

Unsurprisingly, the two projects were linked in Stephen’s eyes. His brother distilled the essence of the connection: In India, “we had enforced peace between rival sects; allowed conversion; set up schools teaching sciences inconsistent with Hindoo (and with Christian?) theology; protected missionaries and put down suttee and human sacrifices. In the main, therefore, we had shown ‘intolerance’ by introducing toleration.” There was no inconsistency between imperial rule abroad and how religious toleration and free speech had been achieved in Britain. Both were elite projects carried out by big government. For Stephen, a liberal and tolerant state was to be defended not because it was a neutral or minimal state, but because it was the best state, run by the best sort of person and generative of a better type of citizenry. In sum, Leviathan, and not On Liberty, was the appropriate sourcebook for enlightened liberalism.

Imperialist, elitist, undemocratic: Stephen champions many of the features of today’s liberalism that its critics find most distressing. But in his support for free speech and his radical pluralism, Stephen exhibits virtues that are lacking in today’s liberal elites, for whom speech-hygiene, panic about misinformation, and punitive regulation of private life and civil society are becoming articles of faith. If present liberals don’t condemn democracy and universal suffrage with the vitriol that Stephen did, they nonetheless lack the self-aware sensitivity to the limitations of claims of expertise that comes through in the gruff Victorian’s acknowledgment that expert rule could never be neutral between visions of the good, never merely a matter of technical fluency or scientific bona fides.

From this recognition it followed, for Stephen, both that members of the professional-administrative class would be well served not to curtail public deliberation nor to close themselves off from even those segments of the populace they might most deplore, and that there was no skirting the great responsibility involved in the morally fraught choices that inevitably faced those wielding coercive power.

Contemporary liberal elites, in comparison, look both more self-satisfied and less secure than the elites for which Stephen called. They often speak as though disagreement with their priorities and prescriptions is a matter of simply having gotten the science wrong, or of giving in to phobias that no good person could abide. But they also seem more timid in their deference to emotional and abstract appeals, at least those issuing from the self-appointed spokesmen favorably regarded groups and interests. Stephen, by contrast, thought that a liberal state capable of achieving great projects and ruling rationally in the public interest required leaders with the confidence to stand against social movements and outbursts of popular moralism; it demanded what to many would seem a certain hardness of heart.

No democrat or anti-imperialist can accept Stephen’s worldview. But his bracing unsentimentality does enable us to ask what we might hope, and fear, from the return of a more aggressively technocratic strain of liberalism we are witnessing.