On Feb. 26, 1988, Mikhail Gorbachev received a pair of Armenian writers at the Kremlin. One was the journalist Zori Balayan, an intellectual architect of the movement for Armenian self-determination inside Soviet Azerbaijan—a movement that was just then roiling the South Caucasus and, for Gorbachev, bringing into sharp focus the nationalist troubles that would soon unravel his Communist empire. The other visitor was the poet Silva Kaputikian. Both were loyal Communist Party members, and they framed their appeal in terms of the interests of the Soviet Union.

At one point, they pulled out a map of the USSR published in Turkey—a map used, the pair claimed, to educate Turkish children about their true geographic inheritance as Turks. On it, a vast region stretching from Central Asia across the Caspian Sea and into the North and South Caucasus was painted green—including Armenia. “Turkey,” Balayan later recalled telling Gorbachev, “is teaching this map in school that all these territories are Turkish.” Gorbachev was unmoved. He briefly examined the map before pushing it back toward the Armenians.

“This is some kind of madness,” declared the Soviet supreme leader.

“Nearly every structure showed signs of shelling damage.”

More than 34 years after that meeting, the mad fantasy dismissed by Gorbachev is edging its way to reality in places like Sotk, a hamlet of fewer than 1,000 people in far eastern Armenia that came under shelling from neighboring Azerbaijan in September. The assault was part of a brief but deadly incursion that saw Azerbaijani forces penetrate well into Armenia proper—as opposed to Nagorno-Karabakh, a disputed, and heavily Armenian, territory inside Azerbaijan that was partially recaptured by the Azerbaijanis in 2020.

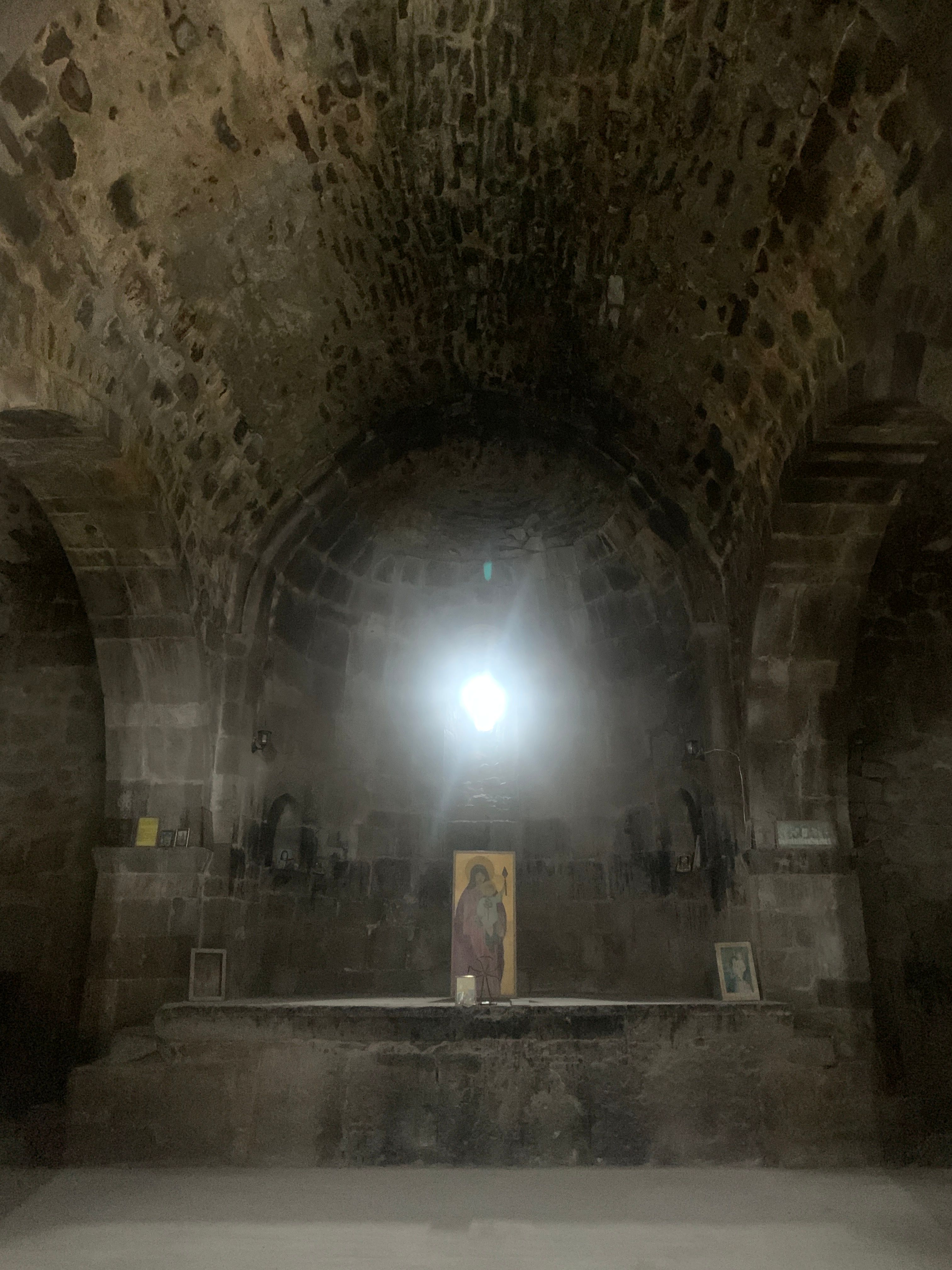

I visited Sotk in October, about a month after Azerbaijan’s assault. A centuries-old church at the center of the village stood unharmed, silently attesting to the indigeneity of Armenians and of Christianity—the two identities are inextricably linked—in this region. But nearly every other structure showed signs of shelling damage from the September flashpoint: Barn roofs caved in; windows shattered and replaced by plastic sheets; tractors and other farm equipment twisted out of shape by artillery; most notably, a military barracks nearby bombed out and apparently abandoned by Armenian forces.

“They shelled us from every direction for three days,” a farmer told me as he showed off the damage to his modest dwelling. While nobody died in Sotk, elsewhere more than 100 lost their lives and thousands were displaced. Among the displaced were the family members of the farmer, who sent his children to stay with relatives farther from the border. Having been driven from Azerbaijan during the First Nagorno-Karabakh War (1988-1994), which saw the Armenians take the territory as both sides expelled populations, the farmer asked, “Now where am I supposed to go?”

Closer to the village center, a boy of 6 or 7 proudly showed off casings from the shell that had struck his house, wounding his grandfather. His sister, 4, huddled with their mother inside. They, too, have returned to tend their animals and plant their fields, though every night they leave for safer areas. “The girl keeps asking me if they’re going to blow up this area,” the mother said. Her husband and father-in-law, meanwhile, pointed to their shell-damaged tractors.

More recently, Azerbaijan’s kleptocratic regime has imposed a blockade against the 120,000 Armenian Christians who reside in Nagorno-Karabakh. Authorities in Baku, Azerbaijan’s capital, have cut off the single road that connects the territory to Armenia proper, depriving the region of food, medication, and other critical necessities. They also briefly shut off the territory’s gas amid freezing temperatures—at least the second time they have done so in as many years. Aircraft daring to deliver humanitarian supplies have been threatened with shootdown.

Armenians—the world’s oldest Christian nation and the victims of the first modern genocide—face extinction in a territory stippled by their churches and crosses. Meanwhile, their nation-state risks being downgraded to a rump state by an Azerbaijan flush with natural-gas revenue and emboldened by foreign-policy elites in Washington and Brussels. As Russia, Armenia’s historic protector, recedes from the scene, Armenians are in a race for national survival.

“Mikhail Sergeyevich,” the Armenian writers warned Gorbachev in 1988, “mad ideas sometimes become realities.” So they do.

The conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan wasn’t fueled by ancient, mythical hatreds, not initially, at any rate. Rather, the dispute’s origins lie in the rise of modern nationalism amid the breakup of one imperial order—the great multinational empires that collapsed in the storm of the Great War—and the birth of a new one: the Soviet Union. At its most utopian, the Communist empire sought to bring about the emancipation of many peoples by transcending peoplehood as such. In practice, Gorbachev and his predecessors merely managed to freeze in place the various post-World War I nationalisms for the better part of a century—until one day, they couldn’t.

“The conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan wasn’t fueled by ancient, mythical hatreds.”

In 1918, in the aftermath of World War I, and centuries of first Persian and then Russian imperial rule, Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Georgia were born as independent states. In Armenia’s case, the Turkish genocide of its Armenian population added an especially powerful impetus to independence. Almost immediately, border disputes arose between the Armenians and Azerbaijanis in three mixed provinces: Nakhichevan, Zangezur, and Karabakh.

The status of the first two of those regions—Nakhichevan and Zangezur—was decided in pitched battles waged by the two nationalist sides. Nakhichevan, a sliver of land lodged between Armenia and Turkey, fell into Azerbaijani hands, forming an Azeri exclave, and so it remains today. In Zangezur, in southern Armenia, the Armenians prevailed. In each case, the victorious side achieved a measure of ethnic consolidation—which is to say that it burned the other’s villages and drove out its population.

Left undecided, however, was the fate of Karabakh, which the Armenians call Artsakh. The mountainous spiritual heartland of the Armenian people, it’s where their alphabet was created, and where Armenian statehood endured even as it was extinguished elsewhere by the empires. Karabakhi Armenians retained their independence even through centuries of Iranian suzerainty, with their rulers styling themselves—and being recognized by the Persians as—“shahs.”

The indigeneity of the Armenians to Karabakh is irrefutable, given the presence of centuries-old churches and cross stones. Yet that hasn’t discouraged the current Baku regime from trying its hand at historical revisionism and bogus “archaeology” that involves removing Armenian inscriptions from churches—that is, when it hasn’t demolished memorial sites. These revisionist efforts include a bizarre claim that the Armenians are “interlopers,” who seized the region from Roman or Caucasian Albanians, a long-since-disappeared people not to be confused with Balkan Albanians. As Grigor Hovhannesyan, a former Armenian ambassador to Washington, told me with a sigh, “the nouveaux riches of this world can rewrite history.”

In the event, in 1920, the Red Army rolled in, conquering both Armenia and Azerbaijan. Soon the Bolsheviks would impose their big freeze on all national disputation. But what to do about Karabakh? Among their most fateful decisions, as far as the people of this region were concerned, was to grant Karabakh the status of an autonomous region within the new Azerbaijan Soviet Socialist Republic, having initially contemplated it as part of the Armenian Soviet Socialist Republic.

Their logic—or illogic—has been the subject of voluminous Soviet historiography in the century since. In immediate geopolitical terms, the Bolsheviks were keen to appease oil-rich Azerbaijan, which they hoped would also coruscate as a revolutionary beacon, summoning the downtrodden masses of the Middle East to rise up against their rulers. But as historian Thomas de Waal has noted, there were other reasons, drawing on both older traditions of Russian statecraft and the precepts of Marxist ideology. For one thing, the Soviets took up the Russian imperial model’s insistence that individual governorates should make geographic and economic sense, and by their lights, the Azerbaijan republic wouldn’t be whole without Karabakh, since, for example, Azerbaijani shepherds would graze their livestock in the region. From a Marxist perspective, moreover, the Soviets believed that they could open up new utopian horizons by impelling ethnically diverse peoples to live side-by-side, forcing strangers to become “brotherly peoples.”

Here’s the crazy thing: For a long time, it all kind of worked.

For starters, there were the cosmopolitan foundations bequeathed by centuries of imperial rule. Azerbaijanis, while starting out as a Tatar or Turkic people with origins in the Central-Asian steppes, had already been deeply Persianized; Baku was a profoundly cosmopolitan place by the 19th century, home to many Jews as well as Armenians. Armenia likewise boasted a Tatar minority with its own mosques. Armenians also have profound links with Iran going back to their origins as a nation; the dynasty that Christianized Armenia a few years before the Constantinian conversion was an offshoot of the Persian Arsacids; the Armenian and Persian languages share a remarkable number of cognates. Atop this multinational foundation, the Bolsheviks sought to raise up a drab, secular-minded, Pravda-reading Homo Sovieticus, for whom what was supposed to matter wasn’t Armenian-ness or Azeri-ness, but the joint struggle for actually existing socialism.

And again, it sort of worked. Armenia thrived within the USSR, emerging as one of the most prosperous Soviet republics, owing to the technical and literary talents of Armenians, their seemingly preternatural ability to navigate Kremlin structures, and the Russians’ old affection for an Orthodox Christian nation that had somehow survived the rigors of dialectical materialism. Despite its carbon wealth, Azerbaijan was much poorer, though in later decades, Azerbaijani Soviet leaders managed to turn their republic into a minor regional manufacturing center. Russian was often the lingua franca of the public square—and sometimes also of the bedroom: For there were intermarriages on both sides of the internal Soviet border—an inconvenient fact that today baffles and repels both peoples.

For de Waal, the Achilles heel of Soviet imperialism was obsessive centralization. Although Moscow forced Azerbaijanis and Armenians (and many other rivalrous ethnicities besides) to live next to each other, all relations had to route through Moscow. Thus, these communities never developed a way of resolving their tensions at a lower level, by talking to each other. Instead, if some dispute arose over, say, the allocation of certain resources, both sides would separately dispatch envoys to the Kremlin; often, but not always, the Armenians fared better, owing to their mastery of the ways of Moscow.

For so long as Soviet power was waxing, and Soviet ideology retained its vitality, the thing could be kept together. But by the 1980s, neither was the case. To an extent unbeknownst to Gorbachev, the whole system was coming apart by the time the two Armenian writers visited him to make their case (in February 1988). The sense that the big Soviet freeze was thawing had given the Karabakhi Armenians an opening, which they used to repose the question left unsettled by the post-World War I settlement: namely, the question of their independence from Azerbaijan.

In the weeks and months that followed, peaceful protests gave way to flare-ups of violent intercommunal tension. For a short while, Homo Sovieticus made his last stand, and a nobility shone through his inescapable weakness: For when Azerbaijanis agitated by the Karabakhi uprising staged a vicious anti-Armenian pogrom in the Caspian city of Sumgait, young Communist militants were the only Azerbaijanis to come to the aid of their “brotherly people,” the Armenians. In doing so, they drew on left-internationalist traditions that were fast waning.

War broke out. Both sides committed atrocities: benzene injected into captured soldiers’ bodies, massacres of fleeing civilians, population transfers. Cases of infantrymen looking through their rifle’s sights, only to glimpse former neighbors and friends donning enemy uniforms, were hauntingly common. The Armenians benefited from a combination of zeal, initiative, early access to Soviet arms, and the assistance of the newly unemployed Russian officer class. When the dust settled, in 1994, Azerbaijan lost Karabakh, though no government—not even the Armenian one that had fought for it—formally recognized the newly formed Republic of Artsakh. For the Armenians in Armenia proper, it sufficed that their Karabakhi cousins were secure from potential ethnic cleansing, with a roadway known as the Lachin Corridor linking the two societies. So it was that the Nagorno-Karabakh dispute entered the 21st century, once more in a frozen state.

‘Frozen conflicts” have a way of turning hot. In the years since Armenia’s battlefield triumph, Azerbaijan under the Aliyev regime—headed first by Heydar Aliyev, the former top Communist apparat, and now by his son Ilham—filled its coffers with natural-gas revenue. And it began courting the West, lavishing money on lobbyists who gave Baku a p.r. makeover.

No longer was the Aliyev regime a graftocracy headed by a typical post-Soviet president-for-life. To the United States and Israel, it became a spearhead against Iran; to energy-hungry Europeans, it was presented as a supplement to, or even a substitute for, Russian gas. Baku also deepened its ties with an ascendant and assertive Ankara, now led by President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, whose pan-Turkic ambitions nicely coincided with the Azerbaijanis’ view of Armenians as annoying interlopers. The once-sturdy sectarian divide between Sunni Turkey and Shiite Azerbaijan proved porous enough for regional players with shared material interests.

Armenia, meanwhile, increasingly found itself isolated. To Washington neoconservatives, it didn’t matter that Armenia has a democratic political culture—“it’s a protest society,” as former Foreign Minister Zohrab Mnatsakanyan told me. “Freedom is a fundamental, existential value for the people of this country.” Nor did Armenia’s ancient Christian heritage sway right-wing foreign-policy professionals, just as the fate of Christians had counted for little when Washington weighed the merits of regime change in Syria and Iraq. What mattered, rather, was that Armenia hosts a Russian base, is a member of the Moscow-led Collective Security Treaty Organization, or CSTO, and has friendly ties with Iran to its south. “We ended up on the wrong side of black and white,” as Hovhannesyan, the former ambassador, told me.

This was all more than a little unfair. Armenian independence had been forged in war with Azerbaijan, and in the wake of that war, it was the Russians who stepped up as desperately needed security partners. That was back in the Yeltsin era, when Moscow’s aspirations to join the Western Alliance were taken quite seriously in Washington and Brussels. If Armenians were blameworthy for striking up a friendship with post-Soviet Russia, then so were the Clinton, Obama, and Bush administrations (father and son). As for Armenia’s ties with Iran, those, as noted, go back to pre-Islamic times; the Islamic Republic, moreover, was Armenia’s only trade partner during the First Nagorno-Karabakh War, when a Turkish blockade threatened starvation. The Americans tolerate far worse, in terms of complicated friendships, from other isolated allies.

When Azerbaijan launched its 2020 operation to recapture swaths of Nagorno-Karabakh, the Trump administration was largely AWOL. Meanwhile, some right-wing foreign-policy analysts, such as the Hudson Institute’s Michael Doran, cheered Azerbaijani forces as they deployed Israeli-supplied drones to devastate the Armenians. Largely ignored was footage of fleeing Karabakhi Armenians singing hymns in farewell to ancient churches they would almost certainly never see again. Likewise, the West remained mute as evidence emerged of Erdogan’s Turkey reinforcing Azerbaijan’s regular army with Syrian jihadists, even as it also lent Baku NATO know-how that bested Armenia’s Soviet- and World War II-style military doctrines. In Armenia as elsewhere, “the West” and violent Islamism acted in tandem against indigenous Christians.

More damaging still perhaps was a visit this summer by European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen to Baku, where she signed a gas-supply agreement with Aliyev and effused about the self-styled “Great Leader”: “You are indeed a crucial energy partner for us, and you have always been reliable.” That visit and those words, Armenian authorities believe, almost certainly emboldened the Aliyev regime as it set out to squeeze both Nagorno-Karabakh and Armenia proper. As Deputy Foreign Minister Paruyr Hovhannisyan told me in an interview in October, before the recent Karabakh blockade, “Why go to Azerbaijan and present it as ‘our most reliable partner,’ without mentioning human rights and the war?” Mnatsakanyan, the former foreign minister, was more blunt: “Ursula made a joke of herself.”

Western indifference and hostility are especially painful for the current government in Yerevan, which surfed to power after a 2015 popular uprising targeting Armenia’s ossified leadership class. In place of the old-school nationalist and ex-Communist cliques that took power immediately post-independence, having earned their stripes in the successful 1990s Karabakh war, Armenians voted in the technocratic and neoliberal-ish Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan.

The new premier ran as a peace candidate and has sought to align Yerevan with Washington and Brussels. Indeed, he went so far as to signal displeasure with Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, a risky move that some believe pushed an already-distracted Kremlin to abandon Yerevan when the Azeris carried out their September incursion and the more recent Karabakh blockade. Armenia, moreover, sent troops to NATO’s Afghan mission. Indeed, it was the second-largest per-capita contributor of troops—remarkable, considering it’s a member of Russia’s security organization, CSTO.

And, the critics ask, for what? What did turning our back against the Russian Bear bring us? Did the West come to our aid when the Turks and Azerbaijanis attacked? One of those critics, Robert Kocharyan, Armenia’s second post-independence president and a veteran of the first Karabakhi campaign, has suggested that safety lies in friendship with Russia and Iran, with whom Yerevan should form a defensive entente.

Hovhannesyan, the ex-DC envoy who is closer to the current government, doesn’t buy this line of reasoning. “This is a frivolous theory,” he told me. “Armenia is very negative about Putin’s move: not just strategically, but because it represents 19th-century imperialism. Even when Armenia was totally in the Russian orbit, even then, after the annexation of Crimea, we telegraphed opposition as much as we could short of voting against Moscow.”

Mnatsakanyan, the former foreign minister, who has negotiated with Putin, agrees: “I think that’s impossible. You’re dealing with two sanctioned countries”—Russia and Iran. The Russians, he said, can withstand isolation, but Armenians can’t: “Russia is Russia. They are prepared to live on potatoes. They think like this: ‘potatoes for the motherland.’ It’s not sustainable, but we are talking five, 10, 30 years? They have enough to keep going for a while. For us it’s not sustainable. We feel comfortable with our Western partners.” This, even as he sees through Western hypocrisy: “This is how our ugly world works. Armenia is insufficiently democratic for you, because we are insufficiently anti-Russia? Is this your definition of democracy?”

Even if Armenia returned fully to the Russian orbit, there is no guarantee that it could move beyond its current impasse. Russia is distracted by what turned out to be a disastrous foray into Ukraine. Iran, meanwhile, has amassed 40,000 troops at its border and vowed to respond to any Azerbaijani alteration of the borders of Armenia proper, which would make Tehran utterly dependent on Azerbaijan (and Turkey) for land traffic into the Caucasus and beyond—a situation that even American officials reportedly concede would be unacceptable to the Islamic Republic.

But many in Armenia doubt whether Tehran would actually make good on this threat, given its own internal turmoil. And if the Iranians did act, it could create a potential nightmare scenario: An Azerbaijani-Iranian war would also mean a Turkish-Iranian war—which is to say, a NATO-Iranian war, with nuclear Russia hovering nearby, including 2,000 Russian peacekeepers in Karabakh who could serve as trip wires.

The upshot is that Baku can squeeze and squeeze and squeeze. What do the Azerbaijanis want? Eric Hacopian, an Iranian-born, American-raised Armenian analyst, described Baku’s endgame starkly: “an ethnically cleansed Nagorno-Karabakh, a sovereign corridor [running from Azerbaijan to its exclave in Nakhichevan], and the Gaza-ification of Armenia proper”—i.e., a severely weakened rump Armenian state that the Azerbaijanis and Turks can do with as they please. Or as Deputy Foreign Minister Hovhannisyan put it, “Azerbaijan is trying to push so much on other issues that we forget Nagorno-Karabakh, that we worry so much about the security of our own country, we don’t have time for the Karabakhis”—a struggle that, as one hawkish Armenian lawmaker reminded me, “is the basis of Armenian statehood”: The movement for independence within the Soviet Union, after all, began in Karabakh, not in Yerevan.

“The Karabakhi Armenians must be afforded self-determination.”

That Azerbaijanis have weaker historical claims to Karabakh doesn’t mean they lack any claim or that the territory should be fully “Armenianized.” But it does mean that the Karabakhi Armenians must be afforded self-determination under the rules set up to adjudicate such claims. Add three decades’ worth of relentless and extreme anti-Armenian propaganda to which Azerbaijanis have been exposed, and forcing Karabakhi Armenians and Azeris to live side-by-side today would be much more dangerous than it might have been in the past.

The larger aim, from the Turkish-Azerbaijan perspective, is the realization of a “Greater Turan”—the dream illustrated in the map the Armenian writers showed Gorbachev. “The Turkic world is being reconsolidated,” said Hovhannesyan, the former ambassador. “The only annoying exception is this strip of land called Armenia. Pan-Turkic aspiration is not academic. During Soviet times, Azerbaijan became cosmopolitan with Russians, Jews, Armenians, and others. The country had a more Russian and European milieu, but with Aliyev, in order to gain power, they became [purists].”

It wouldn’t take much to restrain Azerbaijan and its Turkish backers, to persuade them to loosen their chokehold on Armenia. The Biden administration and congressional Democrats, to their credit, were quick to respond to the September aggression, with House Speaker Nancy Pelosi taking a solidarity delegation that many credit with forestalling further bloodletting. Greater US-Armenian security cooperation, more active diplomatic mediation, and clear red lines against Baku, backed by the threat of sanctions, could buy the Armenians time and space to re-arm and restore a measure of balance in the dispute, setting the stage for a settlement of the Karabakh question. Such assistance must be without preconditions: that is, the Armenians mustn’t be pressured to abandon their regional partnerships (with Russia, Iran, and CSTO), lest worse befall them and they find themselves even more friendless.

The pressure, rather, must bear down on Azerbaijan, which as of this writing continues its blockade of Karabakh, threatening 120,000 residents with extinction, while continuing to leak footage of torture meted out to captured Armenian troops—what officials in Yerevan call Baku’s “war porn.” As former Foreign Minister Mnatsakanyan told me, “any bullshit about Azerbaijanis being nice, cuddly people, we aren’t going to buy. Because we watched the footage. The question is: Are we going to wait until there’s a Rohingya [genocide] situation to react?”