Awareness has come to be considered a self-evident good. News outlets carry laudatory stories of local citizens and groups engaging in attention-grabbing feats to “raise awareness” of an illness, an issue, a threat. No sooner do events hit the headlines than social-media profiles alight with filters and flags demonstrating awareness of, and concern for, whatever the Current Thing may be.

Every year, I sift through student research proposals justified on the grounds that they will “raise awareness” of some hitherto obscure peril. No risk is too small for awareness-raising, no fastidious “awareness-raiser” should go without applause. Yet besides “aware,” we might use other words to describe the outlook these activities demand: vigilance, fear, anxiety.

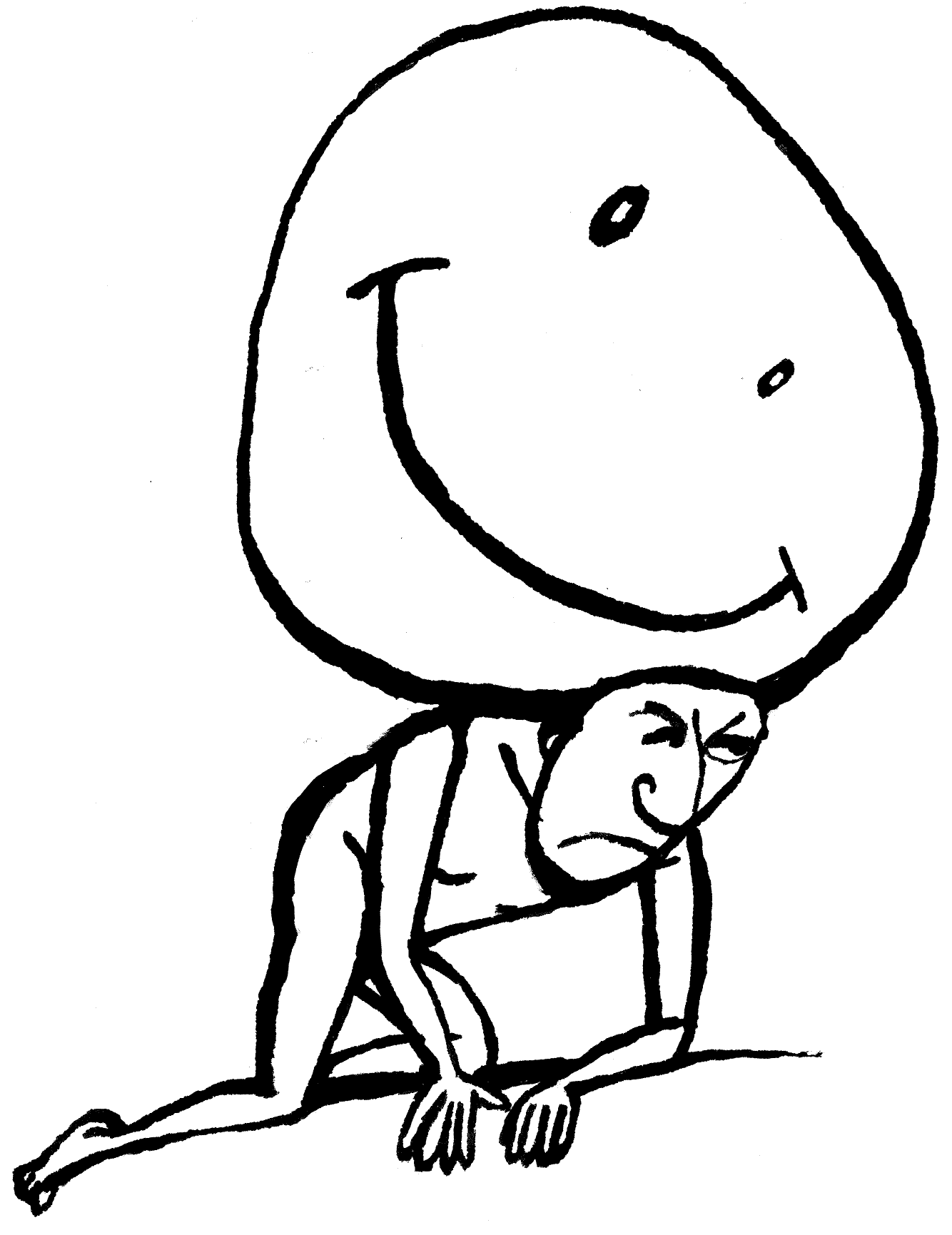

Gradually, the boundaries between “normal” and “pathological” anxiety have become blurred, and illness categories have crept deeper into the ordinary vicissitudes of everyday life. But it isn’t just that the boundaries between normal and abnormal have been obscured—a permanent state of anxiety is itself positioned as a normal and even desirable attribute of the good citizen. In other words, pathological anxiety is the normal response to a world characterized by myriad and proliferating risks.

The virtues of anxiety are implicitly communicated through almost every medium. Fittingly, May is Mental Health Awareness Month, inviting an onslaught of news stories and social-media posts on the precariousness of mental health. May is also Action on Stroke Month, Skin Cancer Awareness Month, and National Teen Self-Esteem Month, depending on where you are. That’s leaving out the dozens of awareness days and weeks dotting the month.