America’s market system delivered more wealth for the asset-rich this holiday season—while serving up hot gall to some of its most essential workers. Last week, the Union Pacific railroad treated shareholders to a dividend payout of $1.30 per share. The capital bonanza came days after President Biden signed legislation blocking rail workers from going on strike.

Rank-and-file rail workers’ demand was eminently reasonable: to have a few days of paid time off. “However well-intentioned,” Biden countered, “any changes would risk delay and a debilitating shutdown.” In other words, sorry, not sorry.

There is a bitter irony in the “most pro-union president in history,” as some Democrats came to tout Biden, slipping a knife into the backs of rail workers. Biden was one of the few senators who opposed then-President George H.W. Bush’s cracking of the whip during the CSX rail strike of 1992. Yet three decades later, Biden has followed his Oval Office predecessors of both parties in suppressing rail workers.

The outcome shouldn’t surprise anyone who remembers American labor history—though, alas, there are few who do. Far from a new phenomenon, averted rail strikes have been an essential feature of American capitalism for nearly a century and a half.

No one celebrated the 145th anniversary of the Great Railroad Strike of 1877, also known as the Great Upheaval, this year, even though it was the first real national strike in America, one that shook the country’s fledgling institutions to the core. Since we have had no significant coast-to-coast strike in decades, our modern equivalent falls somewhere between the George Floyd protests of 2020 (minus the sympathy of one of two major parties, large corporations, and the liberal media) and Jan. 6, 2021 (though the strikers attacked capital, rather than the Capitol).

Depending on which politician or newspaper editor you asked at the time, the 1877 strike was either the Mother of All Riots, a sequel to the Civil War, or an American nephew of the French Revolution. “For a fortnight, there was an American Reign of Terror,” wrote an observer in The Atlantic. A leading newspaper described the events of that summer as one of “civil war with the accompanying horrors of murder, conflagration, rapine, and pillage.” One Chicago paper’s headline screamed: “Terrors Reign, the Streets of Chicago Given Over to Howling Mobs of Thieves and Cutthroats.”

In the late 19th century, there was no such thing as “quiet quitting.” So on July 16, 1877, a few dozen railroad workers in Martinsburg, W.Va., protested against a series of draconian wage cuts handed down by their robber-baron bosses. The workers not only walked off the job, but also stopped rail traffic. That act of defiance sparked a wave of strikes and riots that spider-webbed outward from the Shenandoah Valley across much of the nation’s 80,000 miles of track—mainly concentrating in Northern industrial cities like Boston, Pittsburgh, Chicago, St. Louis, and San Francisco.

Approximately 100,000 workers in 14 states joined in, pulling up tracks along the way and smashing and setting fire to train cars and railroad facilities, stopping half of the nation’s freight. Thomas A. Scott, president of the Pennsylvania Railroad, one of the four rail giants that would later symbolize corporate greed on the Monopoly board, told authorities in Washington, DC, that absent federal intervention, “the anarchy which is now present will become more terrible than has ever been known in the history of the world.” Described by a New York newspaper editor as “the Pennsylvania Napoleon,” Scott suggested the rioters be given “a rifle diet for a few days, and see how they like that bread.”

President Rutherford B. Hayes agreed that the labor “insurrection” needed to be quashed at the barrel of a gun. He ordered regiments of armed troops to strike sites in Pittsburgh, Baltimore, and Chicago. Gatling Guns were wheeled into place in the face of striking workers. Some federal armies were recalled from the Indian Wars of the West, and the fragile Reconstruction governments of the South and some troops who had fought in the Civil War once again turned their guns on their fellow countrymen—this time not on behalf of Abraham Lincoln and the Union cause, but Hayes and wealthy railroad bosses. Militias and police killed at least 117 American citizens in the ensuing fighting; many more were wounded.

By the end of the summer, the defiant workers were bloodied and beaten. The smoke cleared. And the trains began running on time again.

These weren’t great times for railroad workers. Their bosses fired and sometimes blacklisted striking employees. Still, organized labor federations rose from the ashes of the Great Railroad Strike over the next decade, including the Knights of Labor and the American Federation of Labor. “The events of 1877 gave a great impulse and activity to the labor movement all over the United States and, in fact, the whole world,” wrote Albert Parsons, one of the eight labor activists sentenced to death over Chicago’s Haymarket riot, in his autobiography.

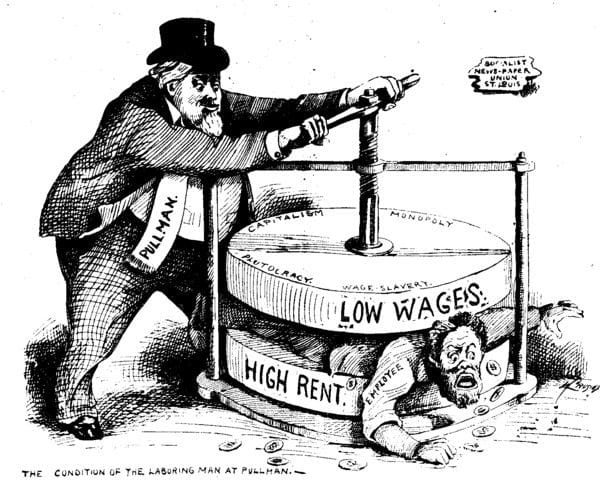

History repeated itself a decade and a half later, during the Pullman Strike of 1894. On Independence Day that year, President Grover Cleveland ordered federal troops to Chicago to join thousands of armed police and guardsmen to break up masses of unarmed strikers who crowded the railroad yards to protest wage cuts at the Pullman Co. Over the next three days, riots broke out, and hundreds of railcars were burned. Violence erupted after a railroad agent shot one of the boycotters, and dozens of civilians were killed in the weeks-long mayhem that followed.

It wasn’t all for naught. Over the long term, labor agitation helped usher in child labor laws, the eight-hour workday, minimum and overtime wages, and legal protections for collective bargaining.

Thanks to New Deal reforms, labor battles over the past century have been less dramatic. But that doesn’t mean rail disputes vanished—they just got a change of scenery, from city streets to smoke-filled rooms. A lot of smoke-filled rooms, actually. Since the passage of the Taft-Hartley Act in 1947—corporate America’s legislative counterattack against the growing power of the New Deal-era labor movement—every single commander-in-chief not named George W. Bush or Donald Trump has been guilty of halting rail strikes dead in their tracks. Obama in 2011. Bill Clinton in 1997. Ronald Reagan in 1982. Jimmy Carter in 1978. Gerald Ford in 1975. Richard Nixon in 1972. Lyndon B. Johnson in 1964. JFK a year prior. Eisenhower in 1953. It’s seemingly the one thing Republicans and Democrats have all shaken hands and agreed upon.

References to this rich history are scarce in most contemporary media accounts of Biden’s turn at strike-busting. This memory-holing is odd. These days, America’s chaotic history, especially when it touches upon “marginalized people,” is constantly being reimagined and recontextualized. The New York Times’ 1619 Project, published in book form a year ago, is being canonized in some circles and demonized in others. Confederate statues are coming down, while icons of Native and African Americans are going up. The anniversary of the Stonewall riots is fast becoming the new July 4th for urban liberals.

“Labor history? For liberals, that sounds too white. For conservatives, too commie.”

Conservatives, meanwhile, just keep doubling down on the nation’s Founders and defeating the Nazis. Trump’s 1776 Commission, his administration’s answer to 1619, didn’t mention the labor movement once—everything that happened between the Civil War and D-Day got the yadda-yadda treatment. Labor history? For liberals, that sounds too white. For conservatives, too commie.

Those of us who dream of a more muscular American working class gaze longingly across the Atlantic, watching waves of angry workers grinding trains, planes, and even garbage trucks to a halt all over Western Europe. They are protesting skyrocketing inflation and paychecks that aren’t keeping up.

Meanwhile, America’s bipartisan elites continue to showcase their singular talent for waging class war and kneecapping unionism. The fact that we don’t even try to remember our labor history is among their chief advantages.