Although I am loath to use the phrase, I don’t think it’s remiss to call Donald Trump’s victory last week a “vibeshift.” Of course, there were substantial issues at stake, but the results were ultimately about how we live and how we feel. Something emotional and psychological was left behind and rejected.

Barack Obama, the leader who inaugurated the era of politics that has now come to a definitive end, preached about the moral arc of the universe bending toward justice, while bending it toward self-enrichment for a select few (including himself). He established a new hierarchy in American culture: a chosen class of elite progressives at the top, a bureaucracy of unofficial commissars in the middle, and underclass of regressive plebs at the bottom. Obama’s smug pragmatism thus evolved into HR culture (Human Resources or Hillary Rodham—take your pick). This puritanical order reached its peak in the late 2010s after Clinton’s loss supercharged the moral certainty of the post-2008 Democratic base.

A new secular religion emerged, with “In this house we believe…” signs displaying its catechism. Identifying with Trump was portrayed as monstrous, the worst thing imaginable. For eight years, the American psyche was bombarded with negative, often fabricated stories about Trump—hoaxes, out-of-context quotes, and conspiracy theories. Relationships ended, marriages collapsed, jobs were lost. Pointless protests and cultural mini-revolutions raged. Dissenters faced punishment without due process—reflecting a manic Calvinist certainty, complete with its elect, sinners, and rituals of public shame. Yet this claustrophobic, self-satisfied paradigm has now produced exactly what it feared most: Trump’s decisive popular-vote win.

“Americans are tired of the progressive panopticon.”

This election thus established conclusively what we’ve known for years: Americans are tired of the progressive panopticon—its constant watching, judging, and elimination of skeptics and dissenters. They don’t want to watch and be watched; they don’t want to spend so much energy figuring out who is elect and who is saved.

Tony Hinchcliffe’s “garbage” joke moment signaled something necessary: We’ll break taboos; we’ll laugh; you’ll laugh; you won’t be offended; that’s part of national politics now. Anyone who saw the Tom Brady roast earlier in the year could have seen this coming. Arguably, that was the night Trump won the election. Brady’s bros roasted him in the crudest, raunchiest ways possible. It’s on Netflix. Hinchliffe was one of the breakout stars.

After the Madison Square Garden rally, the media predictably crowed that Hinchliffe had lost Trump the Latino vote. I felt otherwise. Perhaps, on the contrary, Hinchliffe made Latinos feel part of the Trump coalition. I laugh at you; you laugh at me; you’re American too; you’re my bro. Hinchcliffe made a lot of crude jokes. Essentially, he was saying, “You can take it.”

Biden’s slip of calling Trump supporters “garbage,” revealed something totally different and totally real: the contempt of the ruling class for ordinary people. It wasn’t a joke.

Trump winning not just despite the Hinchliffe “gaffe,” but in a sense because of it, signals a fundamental shift in the American psyche: We can take a joke; we’re not fragile.

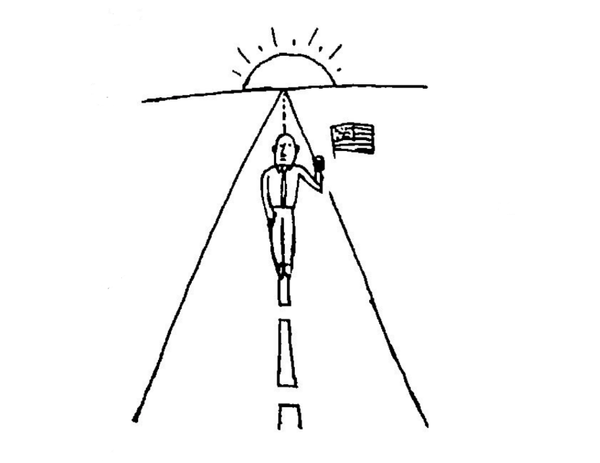

Hints of what people want instead are present in the Trump coalition. Elon Musk, for instance, represents the frontier—space, cutting-edge technology—and the idea that “the future should resemble the future.” People are tired of things getting greyer, sleeker, more “optimized,” but somehow less functional each passing year. RFK Jr, like Rep. Thomas Massie, symbolizes a desire to cultivate health and a rejection of pharmacological solutions, and a respect for and stewardship of land and nature. Vivek Ramaswamy, Tucker Carlson, and Joe Rogan stand for the right to ask “crazy” questions. These figures, all categorized by legacy media as buffoons, failures, and threats to democracy, have all gained traction by suggesting non-elites should get involved, ask questions, disrupt the narrative; that it isn’t harmful to speculate and ask for evidence; that the government shouldn’t keep secrets from us, because we are the government. You don’t have to endorse the specific ideas they entertain to find something salutary in this dynamic.

After the election of Andrew Jackson in the 1820s—when Jackson was essentially disenfranchised in 1824 before being elected in 1828—American artists like Thomas Cole, commissioned by the Federalist gentry, created works that reflected an antipathy toward the transition to a more democratic republic. The 1820s marked a lurch forward shift from a republic governed by a small cadre of hereditary elites (John Quincy Adams) to a Jacksonian republic, where working people could hold administrative positions in Washington.

Jackson himself, like Trump, was a flawed, even enigmatic figure with destructive impulses. But he also had great charisma and practical leadership abilities—a living, walking, talking contradiction. He was a central figure for the American Renaissance, which began in the 1830s (even though many of the northeastern, liberal intellectuals involved in it loathed him). Without Jackson, there would be no Emerson or Whitman: no self-reliance, no containing multitudes, no rejection of the Puritan legacy of conformity in favor of romantic self-confidence.

I suspect—and hope—2024 is a moment like 1830: a time of transformative technology, elite failure, populist revolution, intellectuals turning toward the romance of the frontier. Neither conservative nor liberal, this model is willing to entertain both modes in contradiction, comfortable with uncertainty, self-reliant, fatalistic, but also vital and expansionary. It is essentially Emersonian, rather than Nietzchean. And it might be pretty awesome.