The Two-Parent Privilege: How Americans Stopped Getting Married and Started Falling Behind

By Melissa Kearney

The University of Chicago Press, 240 pages, $25

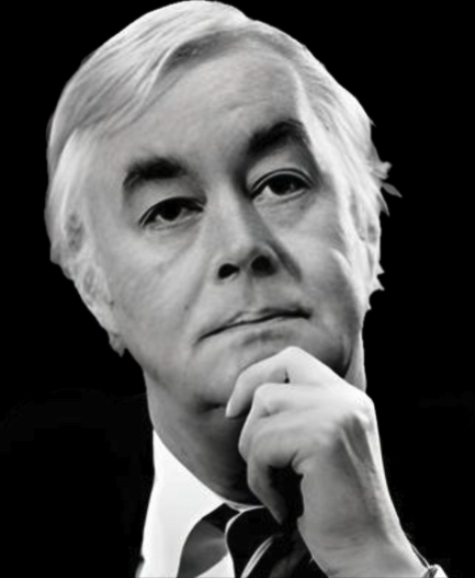

In 1965, then-Assistant Secretary of Labor (later US Senator) Daniel Patrick Moynihan sounded the alarm in his report on the state of the black American family. Black families, he noted, had a far higher proportion of children born to single mothers (24 percent at the time) than white families (3 percent), a higher proportion of families headed by women (21 percent compared to 9 percent), and a higher rate of divorce (5.1 percent compared to 3.6 percent). Moynihan cited research showing that children growing up in one-parent homes performed worse in school and were more likely to be arrested.

“Nearly 60 years later, Moynihan’s findings look almost quaint.”

Nearly 60 years later, Moynihan’s findings look almost quaint. As of 2019, nearly half of all births are to unwed mothers, and as the economist Melissa Kearney shows in The Two-Parent Privilege: How Americans Stopped Getting Married and Started Falling Behind, this troubling statistic transcends racial lines. Seventy-seven percent and 38 percent of white and black children, respectively, and 63 percent of children overall, live with married parents. The data and statistical methods available to social scientists have improved since Moynihan’s time and Kearney, a professor at the University of Maryland, has made full use of them in her research on the economics of the family. The author skillfully summarizes the state of the academic research, while maintaining accessibility for an audience of non-specialists.

Kearney shows that most children growing up without married parents are neither the products of divorce nor of cohabitating biological parents, but rather single moms who were never married to the child’s father. This data point refutes the more optimistic theory that Americans have adopted a more European lifestyle with unmarried but cohabiting parents. It also disproves the notion that many unpartnered mothers are financially well off “super-moms” who obtained a child via surrogacy, in vitro fertilization, or adoption. In reality, the typical single mom lacks a four-year college degree and has a lower income than the median American household.

The fact is, single-parent homes propagate economic inequality intergenerationally. Children who grow up in single-parent homes tend to perform worse in school, have lower incomes themselves in adulthood, and are less likely to climb the income ladder. While college graduates continue to shower their children with resources within married two-parent homes, the children of less financially stable parents fall further behind.

Statistically literate people won’t find much to dispute in Kearney’s presentation of the facts. But Moynihan’s data work, which essentially tabulated averages by race, was also fairly straightforward. Nevertheless, as was the case in Moynihan’s time, the mere mention of these figures will predictably attract accusations of “victim blaming,” effectively shutting down any discussion. Kearney, perhaps attempting to forestall such criticisms, adds the disclaimer that living with two biological parents isn’t optimal in all circumstances.

With this caveat in place, Kearney raises a question many are uncomfortable with today: If parents have the best interest of their children at heart, and two parents can usually offer more resources to their children than one parent, wouldn’t it be optimal to encourage more two-parent homes? If so, we presumably need to know more about what’s causing family breakdown in the first place.

Kearney claims that some of the rise in single-parent households can be traced to the decline in “marriageable men,” a term credited to the Harvard sociologist William Julius Wilson. Essentially, a man’s appeal as a potential spouse depends on his income and steady employment. Moynihan was ahead of his time in alluding to the same idea in the 1960s. He cited the high rates of unemployment for black men and observed that black women tended to be better represented than black men in more prestigious occupations. Two decades later, Wilson coined the term and extended Moynihan’s analysis in his book The Truly Disadvantaged: The Inner City, the Underclass, and Public Policy.

Applying the same concept, Kearney documents that over the last 50 years, wage incomes of men without a college degree have declined relative to men with a college degree and women generally. Indeed, depending on the price deflator and the definition of income one uses, the median real-wage income has declined for the least educated. Not coincidentally, argues Kearney, marriage rates have plummeted within this group. In 1960, close to 90 percent of men ages 30 to 50 with and without college degrees were married. By 2020, that figure was approximately 70 percent for men with college degrees and 55 percent for men with high-school degrees. Although common cultural factors have caused men and women to marry later or forgo marriage altogether, the decline in marriageable men has caused marriage rates to fall the most among those without college degrees.

Perplexingly, though, increasing the pool of marriageable men doesn’t appear to lead to more marriage. In research co-authored with Riley Wilson, Kearney showed that the fracking boom, which increased the earnings of less educated men, didn’t boost marriage rates. While the number of births went up with the rise in income, the share of births to unmarried women didn’t change. Conversely, the coal boom that hit Appalachia in the 1970s coincided with an increase in marriage rates and a rise in fertility among married women, but not unmarried ones. An explanation consistent with these facts is that the decline in marriageable men has set a new norm of less marriage and more single parenthood. And once that norm is established, it is difficult to reverse.

Turning to solutions, Kearney favors the usual center-left buffet of expanding the safety net, raising spending on K-12 education, and improving access to college and vocational training. However, even if the United States did entirely go the way of Denmark, resource gaps between two- and one-parent households would persist. In cases where marriage is very undesirable, Kearney argues that increased involvement of the nonresident parent, provided it is safe, would benefit the child. Mentorship programs, such as the Big Brothers and Big Sisters, have been linked to less drug use and better school performance for the children matched with mentors. Finally, parenting lessons and support classes have some success at improving parenting skills and childhood outcomes.

Changing the culture is inevitably more difficult than pulling on economic levers, but it could be even more important. On this, Kearney’s academic work with Phil Levine is insightful. In a paper published in 2015, Kearney and Levine showed that the spread of the MTV show 16 and Pregnant, which chronicled the challenging lives of teenage mothers, caused a meaningful decline in teen childbearing. A lesson from this research is that messaging matters. If the culture—and here I’m talking about schools, neighborhoods, and, probably most important, social media—emphasizes the benefits of a two-parent household, then we may get more of them.

It’s unclear whether Kearney’s admonitions will prove more consequential than Moynihan’s, although there is some reason to think they might. For one thing, unlike Moynihan, who never expected his report to be read by the public, Kearney avoids provocative terms like “pathology.” In one of her chapters, she convincingly argues that the rise in single parenthood was not caused by a more generous provision of welfare, effectively distancing herself from the culture-war debates of the 1980s and ’90s. She essentially tells her well-educated readers to “preach what they practice” in norms around marriage and parenthood—but she avoids this phrasing as well as any mention of Charles Murray who popularized it in his 2012 book, Coming Apart. (Kearney does cite Murray in the endnotes.) Most important, while racial differences still exist, the broad incidence of single parenthood across groups has reduced the salience of race, perhaps making it easier to talk about.

Will it be enough? Notably, despite the obvious parallels, Kearney doesn’t mention the Moynihan report. This probably says more about her audience than the author. For better or worse, Moynihan carries baggage. And not just the obvious baggage of insensitive language and debatable social science, but the baggage of liberal guilt. The inability or unwillingness to maintain a strong social norm of marriage has done harm to countless children. In Moynihan’s obituary, William Julius Wilson called his report “prophetic”; tragically, not much has changed in the 20 years after his death.