‘He let his eyes run over the sea’s great expanse and set his gaze adrift till it blurred and broke in the monotonous mist of barren space.” This scene from Thomas Mann’s Death in Venice came to mind when I learned of David Graeber’s death nearly four years ago. Like Mann’s protagonist Gustav von Aschenbach, David decamped to Venice as a celebrated author sorely in need of a vacation. Shortly after completing the manuscript for what became his 19th book, The Dawn of Everything (co-written with the archaeologist David Wengrow), he unrolled his towel on the same beach where Aschenbach expires at the end of Death in Venice. The poignancy of the moment gave him no premonition. “I’m in the midst of so many things,” he texted me the day before his heart gave out in a Venice hospital. He was 59.

I waved my way into David’s midst with a fan’s note circa 2007, a few years before his prominent role in Occupy Wall Street and the publication of Debt: The First 5,000 Years catapulted him into public-intellectual status. Back then, I was discharging the disillusioned remains of a lectureship at Harvard. Hearing that Yale had moved to purge David from its anthropology faculty, I wrote to express my unsurprised sympathy. He was a decade older and leagues more accomplished. He grew up Jewish and radical in Manhattan, a milieu foreign to my upbringing in rural Pennsylvania. Still, we met on the same wavelength. Reverse snobbery toward the Ivy League is a rare frequency.

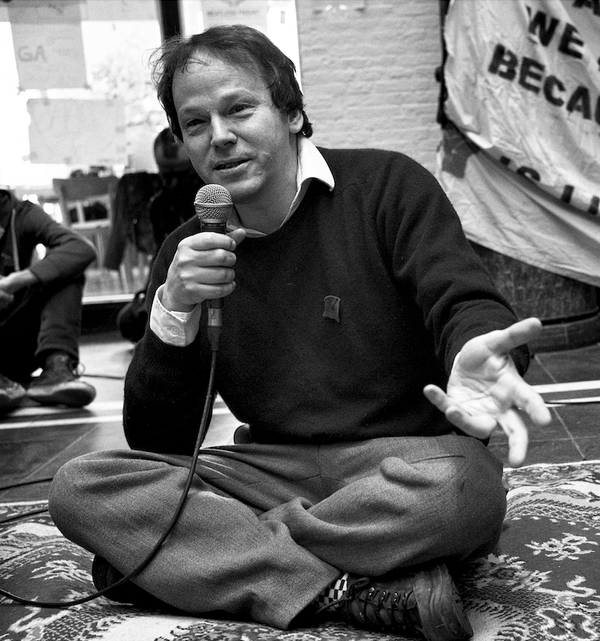

Once I began editing The Baffler, the left-wing quarterly, I invited him to contribute from London, where he had wound up. He should write about whatever he fancied. I didn’t expect him to fancy auditioning his essays over the telephone in torrents of extemporaneous talk, interrupted by snorts of delight. Dialing into David’s giggle bewitched me into a friendship that overran and outlasted the workaday editor-writer relationship. As he talked, his ideas flowed in a companionable blend of earthiness and erudition. When the line went dead, the grief felt caducous, as though some part of myself fell away. The strangeness impelled me to wonder whether I had overlooked some larger property or principle at play in the tonic of his conversation.