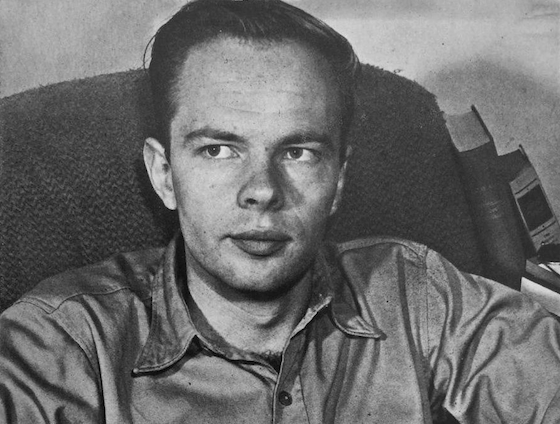

The arrival of ChatGPT has placed artificial intelligence at the center of US discourse. Not surprisingly, one touchstone for these debates have been the novels of sci-fi author Philip K. Dick. As it happens, this AI-inspired interest in the author of Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?, among many other visionary works, comes at a time when American policy elites are also gripped by a new urban malaise—another constant motif in Dick’s body of work.

Today, this pair of Dickian concerns—the rise of the AI era and urban decline—are assigned different weights by the left and the right. So far, it’s mostly progressive institutions like The New York Times sounding the alarm about the risks of unhindered AI. The mostly libertarian-inflected right, by contrast, has taken a predictable “Let it rip!” attitude, the better to punish coastal liberals whose “bullshit jobs” are threatened by platforms like ChatGPT.

Meanwhile, America’s urban malaise codes as a right-wing concern, with conservative politicians and media determined to make electoral hay of disorder in the cities, a situation that they charge has been exacerbated by liberal politicos’ lax approach to lifestyle crimes. Among conservatives, the term “blue city” is permanently (and not wholly unjustly) linked with needle-strewn sidewalks, homeless encampments, and rampant shoplifting.

The two issues are, in fact, closely entangled, in a way that Dick saw clearly but that has often eluded both his cinematic interpreters and the elites who have sought to understand the present by examining his imagined futures. A minor episode in the intellectual history of Los Angeles illustrates this. That was the last time American officialdom turned to Dick as a prophet, albeit via Blade Runner, Ridley Scott’s cinematic adaptation of Do Androids…?

In 1988, some 150 eminent citizens of LA—leaders in politics, business, academe, and philanthropy—submitted a report to then-Mayor Tom Bradley outlining their ambitions for the city as it prepared for the 21st century. In the most notable contribution, the California historian Kevin Starr paid tribute to generations of Angelinos for embracing a “headlong futurity”: constantly adapting the environment to their visions, natural limits be damned.

Yet Starr wasn’t without his fears. The LA of the 1920s—an era of dramatic growth, when the city had willed its water, railroads, and housing stock into being and then invited a million newcomers—“had a dominant establishment and a dominant population.” He meant white protestants. Yes, their primacy meant “overlooking certain suppressions and injustices,” but the old regime had supplied the “civic unity” needed to sustain cohesion amid explosive growth.

“Where,” Starr wondered, “will Los Angeles 2000 find its community, its city in common?” One answer came courtesy of Dick-inspired sci-fi: “There is the Blade Runner scenario: the fusion of individual cultures into a demotic polyglotism ominous with unresolved hostilities” that would now erupt in violence, now settle down in “negotiated truce.”

“Techno-capitalism and urban dilapidation … seemed to go hand-in-hand.”

As the Marxist geographer Mike Davis, who died last year at age 76, noted, Starr’s offhand remark attested to Blade Runner’s enduring status as the “star of sci-fi dystopias.” The film has become a sort of visual shorthand for a set of persistent American anxieties about biotechnology, corporate misrule, and multiculturalism, projected from the California dream factory onto the rest of the country (and the world). For Davis, it was significant that the dream factory, Hollywood, was located nearby other key Golden State industries, not least computing and biotech, whose business was to slingshot our species into Dickian dystopia.

Yet Davis wasn’t very impressed by Blade Runner as a piece of urban futurism. While boasting whiz-bang effects (by ’80s standards), the movie presented a retread of a much older old, and racially tinged, picture of the future as Manhattan-style “giganticism”: teeming masses of culturally mixed and confused human drones huddling under massive pyramids of steel and glass.

That picture no doubt appealed to the likes of Starr as they sought to place the sole blame for the political-economic dislocations and contradictions of California at the feet of “multiculturalism.” Lamenting the loss of WASP primacy was a lot easier than facing up to the de-industrialization and middle-class destruction wrought by the neoliberal revolution launched by the likes of Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher.

For Davis, the Kevin Starr/Blade Runner vision of Los Angeles (as yellow-peril giganticism) missed something still more crucial: the fact that the advances in technology hatched in California sat next to a “great unbroken chain of aging bungalows, stucco apartments, and ranch style homes”—all decaying as the city entered the third millennium. Techno-capitalism and urban dilapidation, sentient machines and lousy bus lines, seemed to go hand-in-hand.

This overlapping of high-tech and physical disrepair is by now ubiquitous not just in California, but across the United States. In Gotham, where I live, Wall Street’s “Masters of the Universe” are still at it, deploying unbelievably complex algorithms to squeeze arbitrage out of the real economy and into their own asset ledgers. Meanwhile, the roads connecting New York City to its airports are riddled with cracks and potholes that recall the “Third World” (except, many developing nations are actually pulling ahead and frequently boast gleaming new infrastructure). The city itself is filthier than I remember in more than a decade. The subway system dates from the 19th century. The mayor has appointed a rat czar.

America is still the world’s largest and, by some measures, most advanced economy. Yet its “headlong futurity” coexists with a country where bedbugs quite literally suck the life out of prisoners. New York, LA, Chicago, Seattle, and the Bay Area distill this apparent contradiction in especially concentrated form, but it’s a national problem. Indeed, America’s Republican-governed states are in some ways worse, since their low-tax, low-spending model fails to attract the sexy futuristic industries.

Kevin Starr may have sidestepped it, and Ridley Scott underplayed it in Blade Runner, but Dick himself was keenly aware of the strange conjunction of high-tech and material degradation. Many—indeed, most —of his imagined worlds are places where technological prowess sits side-by-side with pervasive dilapidation (of urban environments and of the human stock). And while Dick rarely made the point explicitly—he wasn’t the politically didactic type of novelist too generously celebrated in our time—his novels suggest a linkage between market societies, certain kinds of advanced technologies, and the catastrophic abandonment of the material world.

The world of Do Androids…?, for starters, is reeling from nuclear war that has devastated vast swaths of the earth, resulting in massive population loss and the mutative devolution of many of the remaining people. This remnant is menaced not just by the violent androids who sometimes escape slavery in space colonies and return to Earth—but also by “kipple,” the grimly hilarious, quasi-mystical name given to the principle of accelerating decay that melts away all that was once solid and respectable.

“Authority” here is comprised of several competing mega-corporations, including biotech firms that manufacture the android slaves and private police forces that chase the rebellious ones, plus the United Nations (sovereign states, as far as we can tell, are a thing of the past—the neoliberal dream!). These institutions have given up on combating kipple: There is no restoring the earth, no collective repairing the material here-and-now. Resisting kipple is rather an individual task, and a largely spiritual one, carried out through technologically aided regulation of one’s emotions in response to a degraded planet and participation in a virtual-reality religion.

“Dick himself was keenly aware of the strange conjunction of high-tech and degradation.”

Things “off-world” aren’t much better. And since Dick in many ways imagined a single dystopia spanning several stand-alone novels, we might turn to another classic, 1965’s The Three Stigmata of Palmer Eldritch, for a picture of what happens in humankind’s space colonies. Presumably conceived with grandiose ambition and (literally) starry-eyed idealism by the United Nations, the colonies are, in reality, begrimed by the same sort of dilapidation that characterizes life on Earth.

“Welcome—ugh—to Mars,” one colonist aptly greets a new arrival, the novel’s protagonist. Crews of colonists are assigned to “hovels,” each tasked with helping terraform the Red Planet for future mass habitation. But the projects have apparently fallen by the wayside. The proto-gardens are already withering, nothing really gets done, and the days are crushingly boring —so boring, that the colonists, with tacit UN approval, spend their days getting high on a virtual-reality drug: Picture drooling, zonked-out addicts on Skid Row, only in space. The adventure of space colonization has been “kipplized” before it even began.

Then there is Ubik, the capstone of Dick’s incomprehensibly inventive ’60s period and arguably the towering masterpiece of his entire career. Here, too, an advanced society—one that has managed to defer death itself by biotechnologically preserving the consciousness of the deceased—is at war with the principle of ever-accelerating decay and malfunction.

In the world of the living, coffeepots, doors, refrigerators, and sundry other devices possess AI consciousness—a stunningly prophetic anticipation by Dick of the so-called internet of things—but this doesn’t make them any more useful to human beings under conditions of market society. On the contrary, every interaction requires the user to feed money into the devices before they will operate (and then shabbily at that). As technology advances, the alienation already inherent in commodity production extends to robot-assisted consumption; machines themselves learn to rip you off. Again the same paradox: mind-blowing AI and hyper-connectivity moving in tandem with pervasive inconvenience and general shittiness.

Meanwhile, in “half-life,” the tech-purgatory that helps extend mental existence postmortem, the recently dead must constantly contend with an inexorable force of technological decay and regression. Commodities return to earlier stages of capitalist development, while the human form itself, such as it is, risks collapsing into a void of dilapidation. This dreadful prospect can only be staved off through the application of Ubik, a consumer spray product that temporarily restores an appearance of coherence and integrity to market society—ideology in a can. And Dick concludes the novel on a characteristically unsettling, paranoid note, suggesting that the half-life world and the “living” world are, in fact, intertwined —that they may be one and the same.

Advancement and decay. AI and the opioid holocaust. Machine learning and crumbling bungalows. The internet of things and terrible infrastructure. Smartphones and the scattershot, permanently distracted mind of the American child. These phenomena, as Philip K. Dick foresaw, aren’t necessarily opposed, but go together. Some forms of technology more than others—those that help us take flight to virtuality at the expense of the material world, or that outsource the human animal’s cognition and sociality to machines—seem to coincide with a pervasive degradation. To see this paradox already at work, we need but look around at the modern American city.