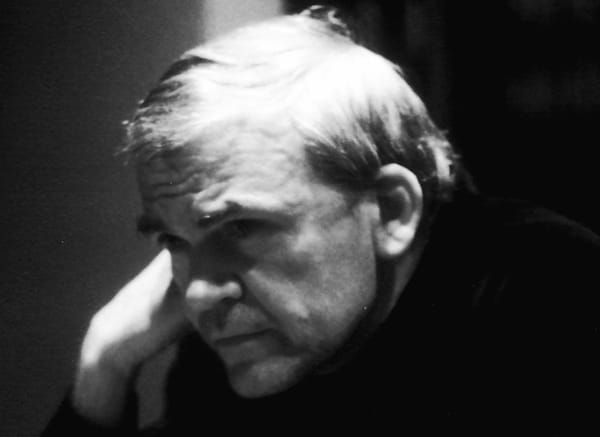

The Franco-Czech novelist Milan Kundera died on Tuesday at his apartment in Paris, aged 94. A passionate advocate of the novel, which he saw as the essential European art form, Kundera came to prominence with two mid-career masterpieces, The Book of Laughter and Forgetting (1978) and The Unbearable Lightness of Being (1984). These formally inventive works bestrode a riven Europe, and with the fall of the Iron Curtain their seductive mix of philosophy, politics, and eros would launch a thousand backpacking trips to Prague.

The lure of a Kundera novel for American readers, I suspect, often had to do with a kind of political voyeurism. As a college student in the late 1990s, I didn’t just identify with the protagonist of The Unbearable Lightness, Tomas, a surgeon who critiques the ruling party, loses his job, and has to wash windows for a living—I wanted to be him. Contemplated from a safe remove, his status as a victim of totalitarian oppression was positively enviable—not to mention that the window-washer job brought the doctor into regular contact with lonely housewives.

The allure of victimhood has hardly waned in the subsequent decades, and many of the obituaries and homages to Kundera have emphasized his role as a Czech dissident (he and his wife immigrated to France in 1975), as if to suggest that the enduring value of his oeuvre consists mostly in its portrayal of life in the Stalinist trenches. One posthumous appreciation says Kundera’s novels “brought news of sophisticated Eastern-European societies trembling under the threat of Soviet repression.” The sex also gets a predictable nod (“RIP to one of the great horny novelists of the 20th century, Milan Kundera”).

But more than a stylish dissident or an apologist of eros—a label that might be applied more accurately to his friend and contemporary, Philip Roth—Kundera could be described as the great revealer of what the French literary critic and philosopher René Girard called mimetic desire in its late, hyperbolic stage. He was a novelist descended not just from Kafka and Solzhenitsyn, but also from Cervantes, Dostoevsky, and Proust.

Human desire, Girard famously argued, is triangular. In general, someone will only desire a given object because he first yearns to possess the being of some prestigious model: I want to wear the same sneakers as my cool older brother or drive the same luxury car as my successful next-door neighbor. Thirst alone is enough to inspire me to order a bottle of water at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art’s restaurant, but only mimetic desire can account for the presence of a water sommelier to help me select one with the appropriate level of alkalinity.

Novelists are well-positioned to unmask the triangular structure of desire, because they excel in setting up scenarios in which characters madly pursue an object of little intrinsic value, accentuating the ironic gap between perception and reality and drawing attention to the model’s influence. In Don Quixote, for example, the eponymous hero seizes an ordinary metal washbasin from an itinerant barber, believing it to be an enchanted helmet, because he is under the spell of his favorite romances of chivalry and wants to see himself as a powerful knight in the mold of his literary heroes.

In Kundera’s oeuvre, the most spectacular illustration of mimetic desire occurs in an early short story, “Doctor Havel Twenty Years After,” in which an earnest provincial newspaper editor is befriended by a suave doctor from the city. Learning of the doctor’s astounding number of erotic conquests, the journalist (who himself aspires to be a womanizer) becomes the man’s disciple, brings his attractive young girlfriend to meet him, and later pulls the doctor aside to ask for his expert opinion. Sensing the master’s disapproval, the journalist immediately dumps his pretty girlfriend, and soon thereafter takes up with an unattractive older woman whom the doctor says would be a better choice. “This great Don Juan,” noted Kundera in a radio conversation with Girard in 1989, “is so sadistic that he always recommends [to the journalist] women who are absolutely ugly.” Whereas “when a girl is beautiful, he says, ‘No, she’s not worth your time.’ And the journalist obeys him completely. So I said to myself that this is almost the caricature—and by the way, I like that short story of mine—of what you have written” about mimetic desire.

Here and throughout Kundera’s work, the revelation of mimetic desire is more than just a comic gag (although it may also be that). “The ‘physical’ and ‘metaphysical’ in desire always fluctuate at the expense of each other,” wrote Girard in Deceit, Desire, and the Novel, the 1961 book where he first laid out his ideas. “This law … explains for example the gradual disappearance of sexual pleasure in the most advanced stages of ontological sickness.”

Those who would enlist Kundera under the banner of hedonism and radical sexual emancipation have things backwards. By emphasizing the primacy of the model’s influence in erotic relationships, the author pointed to the way that mimetic desire, which grows in power when sexual prohibitions fade, tends to empty the world of its weight, its concrete savor, producing a kind of “ontological sickness”—an unbearable lightness of being.

Tomas, for example, can derive no enjoyment from his sex life, because he acts under the compulsion of his sickly desire: “But was it still a matter of pleasure?” the novel’s narrator asks. “Even as he set out to visit another woman, he found her distasteful and promised himself he would not see her again. … He was caught in a trap: Even on his way to see them, he found them distasteful, but one day without them, and he was back on the phone, eager to make contact.”

“He observed that a good novel is more intelligent than its author.”

In Kundera’s Immortality (1990), one character imagines pollsters giving male respondents the hypothetical choice between spending the night with a world-famous actress, on condition that nobody ever knows, and walking through the streets of their hometown with the same woman on their arm, on condition that they never get to sleep with her:

All of them would want to appear to themselves, to their wives, and even to the bald official conducting the poll as hedonists. This, however, is a self-delusion. Their comedy act. Nowadays hedonists no longer exist. … No matter what they say, if they had a real choice to make, all of them, I repeat, all of them would prefer to stroll with her down the avenue. Because all of them are eager for admiration and not for pleasure. For appearance and not reality.

Kundera was a self-described hedonist. Yet he observed that a good novel is more intelligent than its author. His fiction is full of unhappy threesomes (“Even when she was with Eva, whom she loved very much and of whom she was not jealous, the presence of the man she loved too well weighed heavy on her, stifling the pleasure of the senses”); nude beaches characterized by a concentration camp-like uniformity; and would-be libertines who miss out on sex because they are too busy plotting revenge for a nasty comment some stranger flung at them in a hotel bar—scenarios out of Seinfeld, rather than Sade.

Kundera didn’t quite predict the sex recession, or go as far as Michel Houellebecq in taking stock of the ravages wrought by laissez-faire sexual economics. Then again, well-made novels don’t so much supply answers as imply them. At a time when the phenomena he was exploring were already plain to see, if less grotesquely obvious than they are today, Kundera hit on hard truths about the aftermath of the sexual revolution. He was the melancholy prophet of a world where mimetic desire increasingly outstripped the concrete pursuit of pleasure.