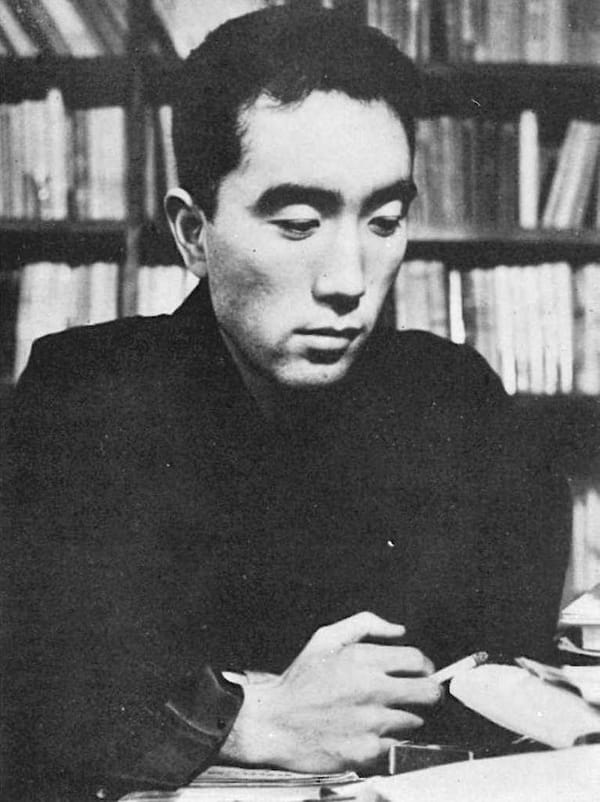

The Japanese writer Yukio Mishima, who lived from 1925 to 1970, styled himself as an “aesthetic terrorist,” and carried out one actual act of terror in 1970, leading a far-right coup against the Japanese government. When the coup failed, he committed seppuku, the ritual disembowelment by sword traditionally reserved for samurai warriors. The combined lurid elements of his persona have made him difficult to categorize. He was a gay, sadomasochistic social conservative and bodybuilder, whose work was both performance art and a celebration of classical Japanese culture. But he’s also an excellent proof of horseshoe theory, one among many of the strange relevancies of his life and work to today’s cultural moment. A new collection published in January of previously untranslated late short stories, Voices of the Fallen Heroes, is minor Mishima, but provides an opportunity for reflection on how “aesthetic terrorism” might affect us today.

John Nathan, the author of the authoritative Mishima biography from 1974 who also wrote the new volume’s introduction, writes that Mishima’s stories “seem to have been written impulsively, dashed onto the page.” They were a sideline for an enormously prolific writer, and Voices of the Fallen Heroes shows Mishima’s range. The collection includes a few gems, and two stories of biographical importance. All should be considered in the context of Mishima’s larger oeuvre.

“Beauty was at its apex in the moment of its destruction.”

“Yukio Mishima” was born Hiraoka Kimitake to an elite Tokyo family of samurai lineage—a Japanese social type that was conservative and backwards-looking, and longed for the glorious past. Hiraoka began writing poetry as a child, and by his teens was publishing work under the pseudonym Yukio Mishima in the decadent style of the Japan Romantic School. The young Hiraoka was enormously influenced, as all young Japanese men of his generation were, by the militarism and cult of a glorious death that flourished in Japan prior to and during the Second World War. He was also attracted to men, a fact he described as “inversion.” From a very young age he chose to conflate beauty and eros with death, and to believe that beauty was at its apex in the moment of its destruction.

Much has been made of Mishima’s psychology and homosexuality—he was a timid youth, dominated by his grandmother and rejected for military service in World War II for being physically unfit. Given this background, it’s easy to see why a weak boy who felt himself an outsider might have had fantasies of strength, violence, and destruction. However, Mishima realized all this himself and was performing a more sophisticated alchemy, overlaying his anxieties onto that of his culture and making a wider cultural statement through art. His persona was part of the act, from the kitschy, queen-y images he generated—posing as St. Sebastian, shirtless, with a sword—to his classic writing on Japanese noh theater. His violent suicide was his last work of art.