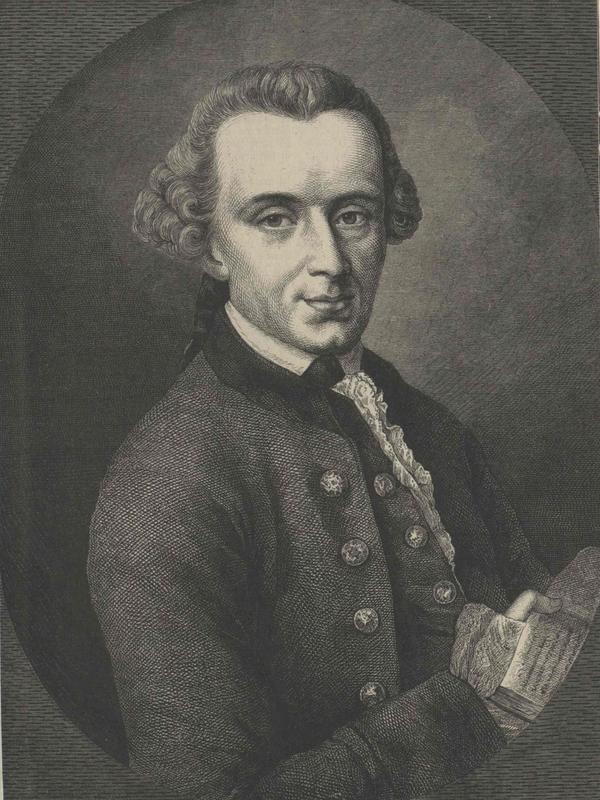

Monday marks the 300th anniversary of Immanuel Kant’s birth. Kant is far from dead today—on the contrary, his thought is more than ever enabling us to see in a new way the horrors of the 20th century, not least the Shoah. Those who perceive the Shoah as the ultimate manifestation of radical evil seem to obtain an argument in Jacques Lacan’s thesis on “Kant avec Sade”—the formula “Kant with Sade” effectively names the ultimate paradox of modern ethics, positing an equation between the two radical opposites: Kant’s sublime, disinterested ethical attitude is somehow identical to, or overlaps with, the unrestrained indulgence in pleasurable violence associated with the Marquis de Sade.

“Is there a line from Kantian ethics to the Auschwitz killing machine?”

A lot is at stake here: Is there a line from Kantian ethics to the Auschwitz killing machine? Are the Nazis’ concentration camps and their mode of killing—as a neutral business—the inherent terminus of the enlightened insistence on the autonomy of reason? Is there some affinity between Kant avec Sade and Fascist torture as portrayed by Pier Paolo Pasolini’s film version of 120 Days in Sodom, which transposes the story into the dark days of Mussolini’s Salò republic?