The resurgent culture wars of the 2020s have caught the LGBT movement by surprise. After what appeared to be a rapid and near-total victory in the preceding decade, the post-pandemic years have seen a series of controversies converging into a furor, as battles reminiscent of the 1990s erupt around school boards and libraries, and bills restricting drag performances circulate through state legislatures. To interpret all this as a mere resurgence of old bigotries, as mainstream commentary often does, fails to account for why these issues have resurfaced in this form and at this time, rather than continuing to fade into irrelevance.

The answer has to do with the crucial metaphorical role that homosexual liberation has played throughout the ongoing sexual revolution, for supporters and foes alike. Over the past half-century, the West has placed sexual freedom at the core of personal, social, and civic self-realization. In this context, homosexuals have embodied the ideal liberated subject—the authentic self waiting to “come out” from under the repressive impositions of social mores. But as faith in this ideal has begun to waver, gays and lesbians have found themselves in the crossfire of proxy wars over the broader legacy of sexual emancipation. To make sense of—and perhaps escape—this predicament requires a rethinking of the history and purpose of the gay-rights movement, which has been plagued from the outset by unexamined contradictions.

An open, organized gay and lesbian movement first emerged in the United States in the wake of World War II, partly as a result of contacts and relationships formed in military service. The military’s policies of punishing, medicalizing, or discharging homosexuals from the service forced servicemembers to band together in mutual defense, bringing out into the open what had previously been an underground subculture and giving veterans a sense of shared identity and predicament. This new self-awareness began to translate into concerted organization in 1950, with the formation in Los Angeles of the first men’s “homophile” group, the Mattachine Society, whose founders included several war veterans; this was followed five years later by the founding of the Daughters of Bilitis, the first civil-rights organization for lesbians.

“The gay-and-lesbian movement has vacillated between conformist and oppositional stances.”

From these earliest years, the gay-and-lesbian movement has vacillated between conformist and oppositional stances toward mainstream society. Although the Mattachine Society was founded by communists who saw their cause as part of a broader attack on bourgeois capitalist society, after the McCarthy period, it and other homophile groups took on a more acommodationist and even conservative cast, admonishing gays to conform their public behavior to mainstream norms. The movement remained relatively small, led by urban intellectuals who campaigned to improve the medical and psychiatric views of their “condition.” Only after the Stonewall riots of 1969 did a new generation reject the medicalization of homosexuality altogether in favor of politicization. At this point, pleas for mainstream acceptance and compassion gave way to slogans like “out of the closets, into the streets,” proclaiming a new pathway to self-respect through open rebellion.

Although the new gay-liberation movement forged out of Stonewall refused to cater to conventional norms, activists nonetheless had to make the emancipation of a small minority relevant and compelling to the rest of society. They squared the circle by casting gays as the vanguard of a general sexual emancipation that would free modern society from restrictive gender roles and the bourgeois nuclear family. The subversion of conventional sex and gender would empower all people to realize their “bisexual potential” in a sexually fluid world, unconstrained by the binaries of male and female, or even of hetero- and homosexual. In the words of Carl Wittman’s “Gay Manifesto,” of 1970, the movement sought “to free the homosexual in everyone.” Radical magazines like Fag Rag yoked homosexual emancipation to civil rights and feminism, translating longtime prophecies of a coming utopian revolution into the sexual realm.

However, the radical argument for gay liberation alienated those gays and lesbians who didn’t see themselves as countercultural rebels, but who wished, in the words of the conservative gay journalist Andrew Sullivan, “to be integrated into society as it is.” In the later 1980s and ’90s, a new, moderate gay politics emerged, coalescing around calls for inclusion in traditional institutions such as marriage and the military. Sullivan, who became editor of The New Republic in 1991, gave voice to this emerging post-liberation gay cadre. In a landmark 1989 essay, he argued for gay marriage on the grounds not only of fairness, but of the institution’s civilizing effect, which would promote “emotional stability and economic prudence” among notoriously promiscuous gays. He optimistically titled his 1995 book on homosexuality Virtually Normal.

Many radical queer activists rejected the new gay politics as a betrayal. Affluent gays, they charged, were trying to “access straight privileges,” instead of dismantling them. Yet the queer activists offered no coherent alternative agenda or organizing focus. An often acrimonious debate continued unresolved in activist circles though the 1990s, but an unintentional synthesis of sorts was finally achieved in the new century, when ostentatious rebellion became, paradoxically, a mainstream norm. The gay movement helped to domesticate social protest as a wholesome middle-class leisure pursuit, to the extent that the Pride parades became stages and testing grounds for corporate marketing. Just one of many examples: On the 50th anniversary of the street riots that launched the gay liberation movement, Procter & Gamble launched a Pantene ad campaign with the slogan, “Don’t Hate Me Because I’m BeautifuLGBTQ.”

In the past decade, the radical queer-liberationist camp was largely absorbed into academia, while the “gay establishment” that once kept queer activists at arm’s length adopted their iconoclastic style and subversive pretensions, all the while enfolding them into the non-threatening imagery of family, home, and career. The result of this awkward fusion is a contradictory queer persona, which presents itself as an iconoclast attacking entrenched norms yet expresses shock and outrage when its actions meet with opposition. The row over the Los Angeles Dodgers’ decision to give and then withdraw a community-service award to the Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence, a drag activist group that satirizes Roman Catholic symbols and rituals, is a recent case in point.

Contemporary LGBT activists attempt to paper over the divide between the oppositional and assimilationist faces of the gay movement by putting forward the provocative persona of the gay underground as a wholesome model of self-expression for all. The aggressive style of 1970s gay liberation is now tamed into gender play for middle-class youth. The most prominent and controversial instance of this phenomenon is Drag Queen Story Hour, which got its start in San Francisco in 2015. These events, the website of the sponsoring nonprofit declares, “give kids glamorous, positive, and unabashedly queer role models.” Ironically, given that drag is a form of play-acting involving ostentatiously artificial personae, the site claims the performances “allow kids … to imagine a world where everyone can be their authentic selves.” Here, self-realization has been redefined as provocative theatricality; while drag’s defenders argue that the art form isn’t inherently sexual, they still must explain why it should serve as a didactic exercise for children—unless we are to understand a form of once-transgressive entertainment as merely conveying a vague conception of personal freedom reduced to camp.

In earlier contexts, drag embodied an ideal of the self as a savvy consumer and performer of cultural kitsch; its irruption into the mainstream reflects the gay movement’s current role as the avant-garde of an urbane middle class that encourages perpetual rebellion while containing and channeling it into narcissistic self-construction. Hence, in addition to the fury Drag Queen Story Hour inspires on the part of social conservatives, it and similar phenomena provoke perplexity and suspicion across a wider swath of society that finds the new middle-class persona distasteful.

Current fights over cross-dressing and transgender issues can’t be as easily disentangled from gay and lesbian rights as gay moderates might like. Sullivan argued in a 2021 interview that the gay movement had basically achieved its aims and, rather than “inventing and creating new senses of crisis” relating to gender identity, it should “shut down and move on.” Sullivan forgets that the gay movement as we know it began as the forceful assertion of a new, subversive identity defined by sex. The gay liberationists he opposed back in the 1980s and ’90s were, as it turns out, correct in arguing that the acceptance of homosexuality would destabilize the whole regime of sex and gender; the toothpaste can’t be put back into the tube.

Additionally, it is tempting for gay-rights supporters to assume that the perception of homosexuality as a symbol of sexual license and hedonism is mere bigoted projection, but the gay movement has often played into the archetype of the urbane libertine. It is no accident that in the early 20th century, the term that homosexual men adopted for themselves was “gay,” meaning carefree and uninhibited, and an attitude of smug aloofness from normal society and its strictures (perhaps a forgivable strategy of ego protection) has attached itself to the modern gay subculture from its earliest existence. The homosexual of today stands in for a conception of the self, running from D.H. Lawrence and Freud through the sexual revolution, as discovered and realized through sexual play. At base, gay activists and their opponents agree in casting homosexuality and gender-bending as metaphors for untrammeled self-assertion, as in performatively anarchic slogans like “be gay, do crimes,” even as this very ideal falls into a deepening crisis.

“The ideal of the sexually liberated subject has reached a point of exhaustion.”

Today, the ideal of the sexually liberated subject has reached a point of exhaustion. The rising generation, although it grew up with greater leeway for sexual experimentation than any before, is actually having less sex than its predecessors, and young activists now weave around the sexual act an increasingly dense web of taboos, obsessively policing age gaps, power differentials, and “problematic” erotic tastes. While usually couched in terms of individual consent, these multiplying taboos reflect a growing fear around the emotional dangers and impacts of casual sex. Similarly, the uproar from the right over drag performances also reflects, in part, a reaction against the threat of sexual anarchy. The progressive and conservative backlashes have even made use of the same terminology: In recent years, both have adopted and popularized the criminological term “grooming.”

The staleness and confusion of contemporary LGBT politics stem from the fact that the movement is conceptually stuck between conformist and oppositional attitudes, unable to define itself except in relation to a putatively stable and oppressive set of dominant norms that, in reality, no longer prevail. The movement survives through increasingly hollow acts of iconoclasm, attacking the last vanishing residues of sexual propriety and gender norms, and through the incorporation of a growing array of arcane niche identities, as reflected in lengthening acronyms and the increasingly baroque Pride flag.

The current impasse has its roots in an assumption that has guided the gay movement as a whole. Whether moderate or radical, activists have consistently minimized the ways in which homosexuality situates its practitioners in a world apart. They have supposed that gay people’s distinctive problems result from discrimination or oppression, which the movement proposes to dismantle, after which the differences between gay and straight people will fade into irrelevance—whether in a new mainstream that seamlessly incorporates conventional gay pairings, or in a radical utopia of gender and sexual fluidity. Both Sullivan’s vision and that of the “Gay Manifesto” assume that homosexual lives can become basically like everyone else’s—in the former case by proposing that gays can mature into the heterosexual norm, and in the latter, by supposing that straight people, once sexually liberated, will become gay.

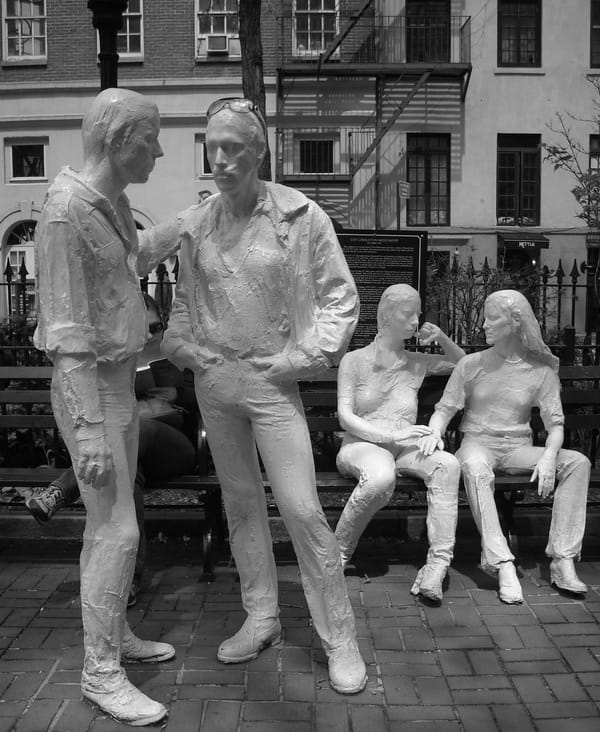

In sum, queer activists have avoided facing the basic predicament of homosexual existence. Unlike straight people, gays and lesbians don’t swim in a sea where most others are like themselves, and where potential sexual or romantic partners can be identified by gender identity and marital status. This is why, historically, they have had to seek out special meeting places. At least since the flourishing of the “molly houses” in early 18th-century London, if not earlier, homosexuals have clustered together in cities and formed sub-societies with their own practices and customs, often veiled in a secret dialect.

What is more, the homosexual uniquely experiences a dramatic clash between the conventional world, where almost no one is a potential sexual or romantic partner, and the gay archipelago, where nearly everyone is. This disjuncture leads to a psychic tension between one’s sexual and non-sexual selves, which gay people often seek to reconcile in opposite ways—either by suppressing their sexual nature to present a sanitized public image, or by erasing the barrier and carrying the overtly hyper-sexual and irreverent persona of the gay underground into public. Most of the internal feuds that have riven the gay movement can be understood as clashes between these two polarized reactions to a basic shared dilemma.

Moreover, the lack of an overarching conception of virtue, beyond hedonism or egoism, has haunted the homosexual movement from its inception. In order to grasp the the implications of this failure, and seek possible alternatives, we must look back to the first explicit effort to bridge the chasm between the gay demimonde and the mainstream modern world—a widely anthologized essay that, rightly or wrongly, has often been claimed as the first harbinger of the modern gay-rights movement.

At the beginning of 1944, the editor and critic Dwight MacDonald—a New York blueblood and one-time wunderkind of the Yale Review turned left-wing radical—quit his post as an editor of New York’s flagship Marxist journal, Partisan Review, and founded his own new monthly, politics. As World War II entered its final phase, MacDonald couldn’t share in his Partisan Review comrades’ triumphal celebration of the Allied advance nor in their optimism about the seemingly imminent prospect of a postwar Western-Soviet hegemony. Over the ensuing year, even as Allied troops closed in on Berlin, he printed pieces from American and European dissidents who deplored the repression of the Stalinist East, as well as the conformism and hypocrisy of the West. While publishing such luminaries as George Orwell and Hannah Arendt, MacDonald also solicited an essay from a comparatively obscure writer: a young poet named Robert Duncan, who had recently emerged from the mystical and theosophical scene in California to become a rising literary star in New York.

The result of MacDonald’s invitation was a short but incendiary essay, which the young poet later described as “a personal agony” to write. Printed in the August 1944 issue of politics under the title “The Homosexual in Society,” Duncan’s article proposed to discuss a group “who have suffered in modern society persecution [and] excommunication” and “whose only salvation is in the struggle of all humanity for freedom and individual integrity.” The essay called upon progressive intellectuals to “recognize homosexuals as equals, and, as equals, allow them neither more nor less than can be allowed any human being.” But the poet saved his most forceful demands for gay writers and artists themselves, known at the time to comprise a large part of the American literary and artistic scene, insisting that they throw off the ingrained habit of concealment, cease to bury their feelings and natures under layers of euphemism, and follow the example of those “Negroes who have joined openly in the struggle for human freedom” and of “Jews who have sought no special privilege or recognition for themselves as Jews but have fought for human rights.”

Duncan’s essay took part in the emerging feud over the meaning of the Allied victory. By spotlighting a form of bigotry of which communists were just as guilty as their capitalist foes (the former condemning homosexuality as a bourgeois decadence even as the latter cast it as a vector of Marxist infiltration), the article furthered MacDonald’s goal of exposing the hypocrisy of his erstwhile comrades. Nonetheless, “The Homosexual in Society” took on a life of its own, outlasting all of the other essays that appeared in the five-year run of politics. The crackdown against gay life in the British and American cities of the 1950s, when raids, outings, and jail terms became subjects of lurid public fascination, seemed to confirm MacDonald’s—and, more implicitly, Duncan’s—warning that the victory over fascism would usher in not a new birth of freedom, but repression in new guises.

Successive generations have found in “The Homosexual in Society” a confirmation of their own sexual politics. In 1959, the editor Seymour Krim, the leading apostle of Beat literature, persuaded Duncan to add further notes and reflections about its writing and reception 15 years earlier. Duncan’s additions included an account of an eminent editor, later revealed to have been John Crowe Ransom, revoking a promise to publish one of his poems because, after reading the provocative essay, Ransom had re-interpreted it as “an advertisement or a notice of overt homosexuality, and we are not in the market for literature of this type.” This story set Duncan apart from older crypto-gay literati like W.H. Auden, who had refused to allow Duncan to write an essay on his work for fear of being outed, and it encouraged his enshrinement as not only a forerunner, but a minor martyr of the gay movement. In the 1960s, the article’s insistence that all “creative life and expression” ought to be directed “toward the liberation of human love” seemed to vindicate the antinomian spirit of the counterculture as well as the New Left’s quest to redeem the authentic self from mass conformity. After the end of the Cold War, the essay’s invocation of “human rights”—and the parallels it drew between homosexuals, Jews, and blacks—appeared to presage the liberal gay-rights moment that began in the 1990s.

Hence, it shouldn’t be surprising that in the current century, the word most often used to describe Duncan’s article has been “pioneering,” nor that it is often credited (erroneously) as marking the author’s early and courageous “coming out.” In 2014, the University of California Press republished the article among Duncan’s collected prose writings, effectively canonizing the poet as a gay trailblazer just as LGBT rights stood poised on the cusp of victory, with the Supreme Court legalizing same-sex marriage nationwide the following year.

“The triumphal moment of the mid-2010s turned out to be fleeting.”

However, the triumphal moment of the mid-2010s turned out to be fleeting. Indeed, the initial disputes over transgender access to bathrooms erupted in the same year as the high court’s ruling in Obergefell v. Hodges. The growing backlash that has followed might have been less surprising if readers had paid attention to the main thrust of “The Homosexual in Society,” which was ignored or played down in the misreadings that have attended the essay’s canonization. Duncan’s principal audience wasn’t the political establishment nor even the wider public, whom he addressed only briefly, but rather the homosexual circles that he saw dominating the literary and artistic scene of the 1940s. Duncan trained most of his rhetorical fire on gay intellectuals who protected their positions by speaking in code. In his words, it was an open secret “at every editorial board” that “a great body of modern art is cheated out by what amounts to a homosexual cult.” (The poet’s wording contains a subtle metaphor, as on stage, to “cheat out” means to angle one’s body partially toward the audience during a dialogue, allowing oneself to be heard while maintaining the partial illusion of the scene.) Duncan denounced gay artists’ subterfuge and, more important, their obsequious dependence both on powerful patrons, whom they “beg” for “privilege for themselves, however ephemeral,” and upon the mass market, for which they “convert their deepest feelings into marketable oddities and sentimentalities.”

While the gay “cult,” in Duncan’s view, deferred to conventional norms by operating behind a veil of secrecy, it fostered an arrogant sense of “superiority” within. Duncan alluded to his own encounter with the urbane homosexual subculture, which cultivated “a secret language, the camp, a tone and a vocabulary that are loaded with contempt for the uninitiated.” He had sought out this hidden world, gathering in “drawing rooms and little magazines,” as a shelter from the hostility of the wider society, but he found it to be an “outcast society as inhumane as the first,” which, “while they allowed for my sexual nature, allowed for so little of the moral, the sensible, and creative.”

In short, the gay clique offered the rising poet “a family,” but a perverse one, in which a forced superficiality reigned—“in which one was not condemned for one’s homosexuality, but it was necessary there for one to desert one’s humanity, for which one would be suspect, ‘out of key.’” The essay’s most personal passage, and the most striking and memorable, describes the author’s feelings after returning from “an evening at one of those salons where the whole atmosphere was one of suggestion and celebration,” which was followed by

the aftershock, the desolate feeling of wrongness, remembering in my own voice and gestures the rehearsal of unfeeling. Alone, not only I, but, I felt, the others who had appeared as I did so mocking, so superior in feeling, had known, knew still, those troubled emotions, the deep and integral longings that we as human beings feel … longings that lead us to love, to envision a creative life.

Duncan contrasted his gay contemporaries’ coy innuendo and oblique self-referentiality with the frank and nuanced depictions of homosexuality in the works of Melville, Proust, and Hart Crane. Moreover, Duncan’s disgust with the secretive “cult” of literary New York surely motivated his lifelong rejection of gay identity. For while his essay has often been credited as his trailblazing “coming out,” the poet actually avoided referring to himself, in the seminal essay or afterward, as gay (in a 1976 interview, he remarked that he “didn’t see [him]self as gay at all”). Instead, Duncan closed his essay by insisting that “one must disown all the special groups” that seductively offer in return “for a surrender of one’s humanity congratulation upon one’s special nature and value.”

In his subsequent writings, Duncan strove, for better or for worse, to present his romantic and sexual attractions as expressions of common human longings, rejecting gay particularism and the blithe and superficial approach to sex he associated with it. He condemned the self-indulgent hedonism of the Beat generation, writing in 1959 that whereas “the fulfillment of man’s nature lies in the creation of … trust” and in “the desire for unity and mutual sympathy,” the new gay poets like Allen Ginsberg had embraced an anarchic and even nihilistic “image of ‘self,’” which led to “the state called ‘Hell’”: “There we find the visceral agonies, sexual aversions and possessions, excitations and depressions, the omnipresent ‘I’ that bears true witness to its condition in ‘Howl’ or ‘Kaddish.’”

Today, Duncan’s condemnation of the “homosexual cult” of the 1940s and of the mischievous Beats of the ’50s may appear prudish and tendentious—a case of “blaming the victim,” or even an expression of self-hatred. However, one must remember that the liberal gay-rights movement hadn’t yet emerged when he was writing. In recent years, we have come to perceive gays and lesbians as the ideal liberal subjects; by contrast, in the mid-20th century, homosexual “superiority,” with all of its aloofness and secret codes, could just as easily be associated with male chauvinism and class or racial elitism. Indeed, two of Duncan’s mentors in the 1940s, the poet Werner Vordtriede and the historian Ernst Kantorowicz, had earlier taken part in the “George-Kreis,” the secretive circle of gay writers in Weimar Germany whose veneration of the male form and of the ineffable German spirit were readily co-opted into Nazism. Hence, Duncan’s essay served in part as a repudiation of the gay subculture’s lingering link to fascism.

“There is no inherent political valence to homosexuality.”

This neglected backdrop of Duncan’s essay illustrates that there is no inherent political valence to homosexuality, and its association with the liberal left is mainly a postwar phenomenon. In more recent years, alternative possibilities have re-emerged: Contemporary cultural conservatives have embraced intellectuals like Camille Paglia and campy iconoclasts like Milo Yiannopoulos, both of whom have used their distinct gay personas to upset liberal pieties. Meanwhile, on the Twitter feeds of a new generation of right-wing androphiles like Bronze Age Pervert—real name: Costin Alamariu—homoerotic imagery and innuendoes blend with calls for a militaristic and hierarchical state. Before launching the BAP persona, Alamariu composed a doctoral dissertation that adopts, like the classical scholars of the George-Kreis, a Nietzschean interpretation of Plato’s dialogues, advocating for authoritarian rule reinforced by erotic bonds among elite men.

In sum, the linking of homosexuality to liberal individualist ideals was by no means inevitable. While it distanced gay life from its one-time flirtation with fascism, it hasn’t rid gay politics of the smug sense of superiority that Duncan observed in midcentury New York. Indeed, Duncan’s description of the camp persona and its aloof self-satisfaction should sound eerily familiar to a contemporary reader, as the midcentury scene’s “contempt for the uninitiated” translates easily into the conceit that gays are models of liberated and authentic selfhood for the vulgar masses.

Even so, Duncan made the same mistake as the queer activists who would follow him in the ensuing decades, in that he assumed that the homosexual dilemma can be subsumed into a broader movement for emancipation. His antidote for the gay circle’s smug superiority lay in the dissolution of difference, as he disavowed particularism and execrated those he called the “Zionists of homosexuality.” While Duncan’s feeling of alienation from the gay “cult” of midcentury New York is understandable, he ultimately offered no practical counsel for countering the persecution of homosexuals other than vague platitudes about universal human rights.

A distinct gay subculture will almost certainly always exist, and will necessarily have to navigate and negotiate its relationship with society at large. Additionally, gay life will always face unique internal problems relating to sex, family formation, and health; while Duncan, the poet, may have been correct that the inner emotions of the gay soul are merely an instance of the universal human experience, the circumstances and contexts that condition them are not. Homosexuality, for better or for worse, will always give rise to a particular world within the world. The main strands of the homosexual movement have sought either to universalize gay idiosyncrasies or to minimize them, leading to a barren cycle of conflict; the alternative is to cultivate shared norms and ideals that respond to the peculiar conditions of gay life.

As it happens, in the late 1970s, a circle of writers and artists led by the editor Michael Denneny formed a magazine, Christopher Street, to serve as a counterweight to the liberationist Fag Rag; the magazine and associated imprint would ostensibly provide a forum in which to build a gay collective consciousness and forge common norms and tastes as distinct from the broader social-radical scene. This project seems in some ways designed to enrage Robert Duncan: the poet’s earlier condemnation of gay “Zionists” is especially noteworthy here, considering that Denneny took inspiration from his mentor, Hannah Arendt, who insisted on a shared moral and philosophical language as a necessary foundation for politics, as instantiated in her wartime involvement with Zionism. Denneny, in his own manifesto of 1981, quoted Arendt’s claim that “a man can live as a man [only] … within the framework of a people.” The Christopher Street project, although deeply colored by middle-class male assumptions, constituted an early effort to build a self-conscious gay ethic in the wake of, and as an alternative to, the hedonistic mood of gay liberation.

Denneny’s project was soon overwhelmed by the catastrophe of AIDS, but its urgency is if anything even more evident today. The most profound crises facing ordinary people in the contemporary West stem not from repressive conformism, as the advocates of hedonistic liberation continue to insist, but from economic conditions that enforce social breakdown and atomization. Today’s rising generations of young people complain not of stifling bourgeois family forms, but rather of loneliness, loss of community, and the inability to form any families at all. Indeed, the greatest dangers facing young queer people, such as the high suicide rate activists frequently point to, are simply intensified forms of the crisis of social isolation facing most everyone in today’s world.

“The gay world has long served as a theater of the search for social belonging.”

Gays and lesbians are, in some respects, well-situated to respond to our era’s tragedy of social erosion. The gay community, if it can be called such, is unique among all demographic groups in ways that make it unusually suited to address the crisis of fracture and atomization. It is defined by sexuality and, therefore, must grapple with the limits and dangers of sexual freedom at a time when the frisson of liberation has given way to disillusionment. Moreover, the gay population is uniquely cross-cutting, drawing from all segments and strata of society, making it a laboratory for the possibilities of social organization across divides. Above all, queer people tend, more often than others, to uproot themselves from their families and communities of birth, seeking out alternative worlds of similarly deracinated peers. In this way, the gay world has long served as a theater of the search for social belonging.

Rather than continuing to chase the false dawn of perpetual liberation or idealizing a normality that is increasingly breaking down for everyone, gays and lesbians might instead draw upon a shared history and build on self-made social networks to fashion a multilayered internal civil society of the sort that has been decimated in the modern West. Gays and lesbians often already serve as models of modern friendship and chosen community. Longstanding gay strategies of survival and adaptation might provide materials for a social renewal, offering possible methods to reinforce social bonds, outside or alongside the natal family, and to define the duties that they entail. While Andrew Sullivan, for his part, is correct in identifying marriage as an “architectonic” institution that can give shape to gay as well as straight lives, he also makes the common mistake of assuming the nuclear family on the one hand and the state on the other are sufficient for a thriving society, to the neglect of the web of social relationships and groups that intervene between them. On these grounds, he regarded state recognition of gay marriage as the final fulfillment of the gay movement, telling the Washington Blade in 2021 that “the core civil-rights ambitions of all of us have been realized,” and that organizations like the Human Rights Campaign should therefore “wind down.”

Alternatively, the gay movement as a whole might reassess its meaning and purpose amid the crises of a new era. Ever since its beginnings in World War II, it has spoken the language of universal rights and principles; but as advocates of homosexual liberation from Duncan onward have often forgotten, the universal must always take its substance from the particular. Today, with both the dream of general liberation exhausted and the pursuit of mere “normality” increasingly at odds with the disorienting social realities that surround us, a new gay politics would need to articulate an affirmative vision of what gay life can contribute to a fractious and atomized world. But this would also mean grappling with the implications—both positive and negative—of belonging to a small and unavoidably strange minority.

Robert Duncan, like later gay radicals, subordinated homosexual equality to a broader struggle for liberation; nonetheless, he also assumed a more nuanced understanding of freedom as instantiated in social relationships and the common good. The liberated self, in his vision, seeks, above all, the trust and understanding of his fellows. Although Duncan always kept a distance from the gay movement, his poetry shows an appreciation of the love shared not only between sexual partners, but among friends struggling for survival and belonging in the gay underground.

Most strikingly, his 1957 poem “This Place Rumord To Have Been Sodom,” imagines, in an eerie prefiguring of AIDS, a ruined city, once a “gathering place of the spirit,” which travelers now pass by, remarking ruefully that “these ashes might have been pleasures.” According to the narrator, the exotic city had been

...measured by the Lord and found wanting,

destroyd by the angels that inhabit longing.

Surely this is Great Sodom where such cries

as if men were birds flying up from the swamp

ring in our ears, where such fears that were once

desires walk, almost spectacular,

stalking the desolate circles, red eyed.

Nonetheless, the haunted ruins serve as a site of renewal, as newcomers salvage and cultivate what was most valuable in the lost city:

The devout have laid out gardens in the desert,

drawn water from springs where the light was blighted.

How tenderly they must attend these friendships

or all is lost…

In the Lord Whom the friends have named at last Love

the images and loves of the friends never die.

This place rumord to have been Sodom is blessd

in the Lord’s eyes.

As Duncan intimates in these lines, the gay community, rather than promising yet more transgression or total assimilation, could instead serve as a proving ground for the formation of human bonds in an age of fragmentation.