In recent years, yard signs declaring that “Science Is Real” have festooned America’s liberal enclaves. Science may have once been understood as a set of imperfect methods for making sense of the material world, but it has increasingly become a partisan doctrine. The pandemic showed that “believe science” was anything but an empty slogan: Political leaders took the unprecedented step of quarantining entire populations and shuttering schools and businesses at a moment’s notice on the basis of deference to “The Science,” and national Covid guru Anthony Fauci declared that any political criticisms of his policy recommendations amounted to “attacks on science.” It was a stunning development, but not a wholly unprecedented one. A generation earlier, another pandemic had laid the groundwork for the cult of science.

In April 2000, the Clinton administration declared AIDS a threat to the national security of the United States. This was the first time a disease had ever been designated as such. Before that, the National Security Council normally didn’t get involved in public health. In making this declaration, then-President Bill Clinton was both playing to his base and listening to the experts. Fighting AIDS had become a popular cause among Democrats, in part due to the visibility achieved by activist groups like ACT UP. Moreover, in the 1980s and ’90s, many feared the disease would spread beyond risk groups and become a general pandemic through heterosexual transmission. This hadn’t happened in America, but it seemed to be happening in other parts of the world, particularly Africa. The director of the Office of National AIDS Policy said, “We are just at the beginning of a pandemic the likes of which we have not seen in this century, and in the end will probably never have seen in history.” AIDS, it was feared, would lead to demographic collapse, which, in turn, would lead to civil war, state failure, and terrorism worldwide.

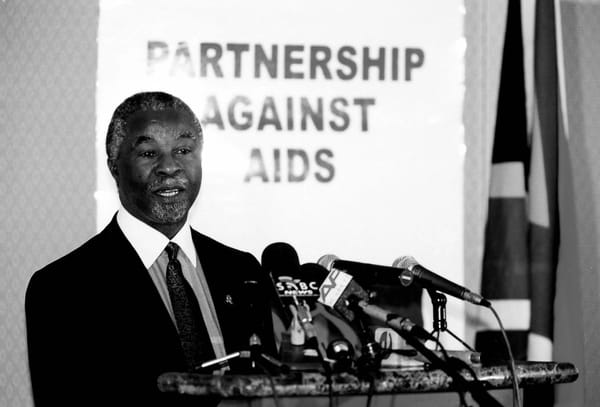

A few months after Clinton’s announcement, the International Conference on AIDS was held in Durban, South Africa. Many participants were alarmed by the actions of South African president Thabo Mbeki, who had convened his own panel of experts to advise him on the AIDS crisis. Though there were mainstream scientists on the panel, Mbeki also included a number of so-called AIDS denialists—that is, people who argued HIV didn’t cause AIDS. Chief among them was the University of California, Berkeley, biochemist Peter Duesberg. After a distinguished career as a cancer researcher, Duesberg had won infamy in the late 1980s as a leading “denialist.” The prospect of him influencing South Africa’s head of state was seen as highly dangerous.

“The AIDS crisis helped bring about a new relationship between science and politics.”

To voice their concerns, a committee of AIDS researchers came together to write the Durban Declaration. The document, signed by more than 5,000 doctors and scientists and published in Nature, declared that the evidence showing that HIV causes AIDS was “clear-cut, exhaustive, and unambiguous.” The signatories further asserted that “prevention of HIV infection must be our greatest worldwide public-health priority.” Members of Mbeki’s panel shot back that the declaration reflected “an intolerance which has no place in any branch of science” and amounted to an “attempt to outlaw open discussion of alternative viewpoints”—to which a couple of mainstream AIDS researchers retorted: “If free speech costs lives, that’s a high price to pay.”

Petitions aren’t normally considered part of the scientific method, but from the start, AIDS had been an exceptionally political disease. Indeed, the AIDS crisis helped bring about a new relationship between science and politics. Science came to dictate intimate aspects of people’s lives and set public policy. At the same time, the appeal to science as the ultimate authority incentivized political organizations and leaders to present their agenda as scientifically correct and to pressure scientists to support it. The result was a double movement in which science became political and politics increasingly claimed to be scientific.

AIDS—before it had a name—entered mainstream American discourse with a 1981 New York Times article titled “Rare Cancer Seen in 41 Homosexuals.” The cancer was a disfiguring condition called Kaposi’s Sarcoma. The Times emphasized that all the gay men featured in the story had histories of promiscuous sex and heavy drug use, adding that “some indirect evidence actually points away from contagion as a cause.” The story wasn’t front-page news; insofar as Americans noticed, they might well have concluded some gays were getting sick due to their unhealthy lifestyle.

Soon, Kaposi and other diseases afflicting gay men were reclassified as part of a condition called Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome. The lifestyle hypothesis was discarded. Instead, most scientists came to think that AIDS was the result of a new infectious agent. In 1984, then-Secretary of Health and Human Services Margaret Heckler announced that “the probable cause of AIDS” had been found. “Today we add another miracle to the long honor roll of American medicine and science,” Heckler said, crediting the National Institutes of Health scientist Robert Gallo for discovering the virus that caused AIDS.

Under the aegis of the War on Cancer, declared by President Richard Nixon in 1971, Gallo had spent the first part of his career studying a newly discovered class of viruses called retroviruses. Retroviruses were believed to be linked to cancer, but years of investigation had yielded few concrete results. Now, however, retrovirology had triumphed by uncovering the cause of the new plague: the Human Immunodeficiency Virus. A few weeks after Heckler’s news conference, Gallo and his team laid out their evidence in four separate articles in the journal Science. Most scientists were convinced—but the causality of AIDS was never a purely academic question.

In his 1996 book, Impure Science, the sociologist Steven Epstein wrote: “What cannot be overstated is that the HIV hypothesis was not simply a scientific powerhouse. It was also—crucially—a social phenomenon.” According to Epstein, most gay-rights organizations at the time favored the viral theory as it shifted the focus away from the lifestyles of gay men, instead suggesting they had simply been unlucky in being the first group to catch it. Moreover, by emphasizing that heterosexuals could also contract the disease, the HIV theory forced the public at large to pay attention.

“Throughout the 1980s, the media exaggerated the threat AIDS posed to the general population.”

By 1985, the first HIV test became widely available. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention soon launched a nationwide campaign to promote widespread testing and safe sex to prevent transmission. AIDS charities often employed publicists to raise public concern about the disease. In practice, this often meant spreading panic. Throughout the 1980s, the media exaggerated the threat AIDS posed to the general population. The resulting panic provided a rationale for jettisoning traditional scientific standards. In 1987, the first AIDS drug, AZT, was approved after the quickest trial in Food and Drug Administration history. AZT was originally developed as a cancer drug. It was thought that AZT could treat AIDS by stopping the virus from replicating. Unfortunately, it was highly toxic and came with severe side effects.

Also in 1987, the group ACT UP formed, taking militant AIDS activism to a new level. At the first meeting cofounder Larry Kramer declared, “You are all going to be dead in five years. Every one of you fuckers…. How about doing something about it? Why just line up for the cattle cars?” This rhetoric was effective at attracting attention and rallying traumatized people, but Kramer should have known it was an oversimplification. He had tested positive for HIV and believed himself to have first contracted the virus in the late 1970s. By the time he gave his 1987 speech, he had been living with HIV for close to a decade without getting sick; he would eventually die at age 84 in 2020. His doom-mongering not only distorted the public’s understanding of AIDS, it also may have hurt AIDS patients themselves. In the 1980s, a positive HIV test was widely perceived as a death sentence; according to the physician and pioneering AIDS researcher Joseph Sonnabend, it wasn’t uncommon for men to kill themselves when they got the news.

This was the volatile atmosphere Peter Duesberg entered when he published his first paper on HIV in the journal Cancer Research in 1987. “Retroviruses as Carcinogens and Pathogens: Expectation and Reality” could be described as the founding document of AIDS denialism. It’s a highly technical text that reviews the evidence for the claim that retroviruses are capable of causing disease. The bulk of the paper is devoted to cancer, but near the end, Duesberg switched to a discussion of AIDS. In both cases, he found retroviruses not guilty.

Duesberg was no crackpot. The year before, he had been elected to the National Academy of Sciences. Moreover, he had been the first scientist ever to map the genetic structure of retroviruses, making him one of the world’s leading authorities on the subject. When laypeople try to follow a scientific debate, it is natural for them to use credentials as a heuristic. Unfortunately, that was no help here. Duesberg had impeccable credentials—but then, so did Gallo and many proponents of the mainstream view. The lay public is hardly more qualified to adjudicate a dispute about retroviruses than one about subatomic particles; only in this case, we were told our lives depended on which side was right.

Duesberg suffered professionally for his heterodox stance. After his paper appeared, he had trouble getting published for the first time in his career, and his research grants weren’t renewed. These slights only made him more intransigent. His initial argument that HIV isn’t sufficient in itself to cause AIDS hardened into the claim that it is a harmless passenger virus and that AIDS isn’t a sexually transmitted disease at all. He proposed, instead, that AIDS resulted from drug use. Duesberg believed that both illicit drugs and pharmaceuticals could cause the immune system to collapse. Most disturbingly, he argued that AZT and other drugs prescribed to treat AIDS could in fact cause it.

Duesberg brought his views to a mass audience with the 1996 publication of his book Inventing the AIDS Virus. He also did his best to reach policymakers but was largely shut down in the United States. Fauci, then the federal government’s leading AIDS scientist, once heard Duesberg speak and responded: “This is murder. It’s really just that simple.” In Fauci’s view, Duesberg was sabotaging science’s ability to save lives. By promoting the idea that HIV doesn’t cause AIDS, he undermined public-health campaigns to stop transmission, as well as the use and development of antiretroviral drugs to treat patients. For his part, Duesberg gave as good as he got, likening the establishment to Nazi war criminals for prescribing AZT. Each side accused the other not just of getting the science wrong, but of killing people.

Between these two poles, there were also those who might be called “AIDS moderates.” The moderates believed that HIV plays a causal role, but that there are also cofactors that lead to the development of AIDS. A cofactor might be another pathogen, or it might be the immunosuppressive effects of drug use or malnutrition. One prominent moderate was Luc Montagnier, who won the Nobel Prize as a co-discoverer of HIV in 2008. Another was the South African-born Joseph Sonnabend, who started a sexual-health clinic in New York City in the late 1970s and was one of the first to observe and treat the cluster of diseases that came to be known as AIDS. In 1983, he helped establish one of the first AIDS charities but resigned in protest in 1985 when he discovered the organization was propagandizing the threat of an imminent heterosexual AIDS epidemic. Sonnabend was also an outspoken critic of AZT, agreeing with Duesberg that it was being prescribed in fatal doses. Yet as a clinician, he took a flexible attitude as the treatments improved, saying, “The issues are not black-and-white. Drugs that can save your life can also under different circumstances kill you.”

In his life and work, Sonnabend offered a glimpse of what the medical and scientific response to AIDS could have been if the disease had not been so relentlessly politicized. In 2000, Sonnabend was a member of Mbeki’s advisory panel. Though he viewed the denialist faction as dogmatic, he also found the scientific establishment’s refusal to debate their critique “unconscionable.”

At the turn of the century, the South African author (and Compact contributor) Rian Malan accepted a commission from Rolling Stone to write about President Mbeki’s handling of AIDS. Malan, an Afrikaner, had been a vocal opponent of Apartheid. Throughout the 1990s, however, he had become frustrated by the way the Western media covered South Africa. Americans in particular were only interested in stories in which the African National Congress were cast as the unequivocal good guys. AIDS, however, was beginning to disrupt that narrative. Many Western liberals who had idolized Nelson Mandela were now horrified that his successor would indulge the deadly quackery of AIDS denialism. Malan jumped at the chance to deliver the president’s head on a platter to the international media. He imagined it would be easy: All he would have to do was count the bodies of AIDS patients.

AIDS in Africa was always a different phenomenon from AIDS in the West. In 1985, the World Health Organization met in the Central African city of Bangui. The so-called Bangui definition was a way to count AIDS cases in the absence of an HIV test. The problem was that the criteria were so general they were compatible with a wide variety of clinical conditions—everything from respiratory illness to severe diarrhea. Eventually, the Bangui definition was abandoned in favor of a case-surveillance method in which blood from African clinics was tested for HIV and then fed into statistical models in Geneva to estimate AIDS prevalence in a given country.

This method brought its own problems. Most sub-Saharan countries lacked the state capacity for reliable data collection, so there was no point at which estimates met facts. Moreover, many of the countries said to be worst affected were undergoing unprecedented population growth. In his essay collection The Lion Sleeps Tonight, published in 2012, Malan wrote about his quest to get to the bottom of AIDS statistics in Africa. What seemed like a straightforward story turned into a fiendishly complex labyrinth. One thing that did become clear was that AIDS in Africa had become an industry unto itself. Activists, nongovernmental organizations, and many medical institutions had an interest in promoting the most catastrophic possible scenario to secure funding. As Malan would put it in a controversial op-ed, “in Africa, the only good news about AIDS is bad news.” The fight against AIDS turned out to be one more simplistic morality tale beloved by Western liberals.

Malan had to conclude that at the very least it was reasonable for Mbeki to seek out a second opinion when the entire establishment was blaring an inflexible message of doom. He found an unexpected source of corroboration in WHO epidemiologist James Chin. Chin was no dissident. He had helped design the model used to estimate AIDS prevalence in Africa and had been a harsh critic of both Mbeki and Duesberg. Nonetheless, in his own 2007 book, The AIDS Pandemic, he acknowledged, “AIDS programs developed by international agencies and faith-based organizations have been and continue to be more socially, politically, and moralistically correct than epidemiologically accurate.” According to Chin, HIV-AIDS estimates were more of an art than a science. Groups like the United Nations Joint Program on HIV-AIDS, or UNAIDS, stepped into this information void by presenting alarming overestimates to win funds for international AIDS programs. UNAIDS claims to be doing virtuous work, and no doubt the organization does help people, but in Chin’s view, it has also wasted a lot of resources and misled the public.

“You don’t need to support Mbeki then to see that the man faced a genuine dilemma.”

You don’t need to support Mbeki, then, to see that the man faced a genuine dilemma. He was the democratically elected leader of South Africa, but international committees of experts were trying to dictate his governing priorities. Public-health NGOs and aid agencies had their own interests, which didn’t necessarily coincide with those of South Africa. Mbeki was told that the science was settled, but when he looked into it, he found apparent anomalies. When he pointed these out, he was accused of denying science. Reflecting on the controversy years later, Mbeki denied ever saying that HIV doesn’t cause AIDS and claimed only to have wanted to look into certain questions. He agreed that HIV could cause immune deficiency but believed his country faced other pressing health problems, as well, and these were being given short shrift due to a single-minded fixation on the AIDS crisis.

Unlike AIDS, Covid fit neatly into an established infectious-disease paradigm. At the height of the pandemic, no scientist of Duesberg’s stature would dispute that it is an infectious disease caused by a virus. On this level, the science was uncontroversial. Still, the new pandemic brought about a fusion of science and politics that surpassed the AIDS era, in which everyday life for the entire population was reconfigured to conform to the dictates of scientific experts and their epidemiological models.

The Trump administration’s Covid response was dominated by Deborah Birx and Fauci, both stalwarts of the lockdown approach. Even so, Trump did occasionally seek out advice from dissenting experts. He hired Stanford radiologist Scott Atlas to advise the White House. Atlas, in turn, arranged for Trump to meet with renowned epidemiologists Sunetra Gupta, Martin Kulldorff, and Jay Bhattacharya to get an alternative view. None of these dissenters was disputing the basic science of Covid. They were simply arguing that locking down society carried with it serious harms. Even this mild form of dissent couldn’t be tolerated.

Before the 2020 presidential election, many of the world’s leading scientific journals took the unprecedented step of making political endorsements. They all came out against Trump, accusing him of denying science. Meanwhile, the scientific establishment worked to silence dissenting scientists. For example, the NIH pressured YouTube to remove a video of Bhattacharya saying he didn’t think children should wear masks.

Bhattacharya first became cognizant of the politicization of the virus when he and his Stanford colleague John Ioannidis carried out a seroprevalence study in California in spring 2020. They found that the virus was already widespread and much less deadly than the WHO estimated at the time. Though it contained no policy recommendations, the study did suggest that attempts to control the spread of the virus had already failed and thus implied that doubling down on such efforts would be futile. To his shock, Bhattacharya was viciously attacked by colleagues and the mainstream media.

Later that year, Bhattacharya briefly met with Trump; during this meeting, the president said he thought lockdowns had been necessary, or else millions of people would have died. Trump had based this conclusion on epidemiological models like the one developed at Imperial College London. Like other world leaders, Trump had been presented with these catastrophic predictions as if they were facts. The Imperial College model turned out to be wrong, but all the same, it continued to dictate policy throughout the course of the pandemic. As Bhattacharya has said, “models are hypotheses”—yet in a strange inversion of the scientific method, the hypothesis had come to take priority over the experiment.

“The epistemological crisis brought to the fore by Covid is also a political one.”

The epistemological crisis brought to the fore by Covid is also a political one. During the period of lockdowns and mandates, a highly politicized scientific consensus came to rule by fiat. As a result, the dilemma Mbeki faced at the turn of the century became a universal predicament. Basic decisions about how we organize our lives were put in the hands of experts, and both ordinary citizens and heads of state felt they had no choice but to “follow the science.” Politicians who sought advice from dissenting scientists were condemned and vilified, as Mbeki had been two decades earlier. These patterns suggest that “The Science”—not actual science, in all its self-doubt and complexity—poses a grave threat to democracy in the 21st century.