Taming the Octopus: The Long Battle for the Soul of the Corporation

By Kyle Edward Williams

Norton, 304 pages, $29.99

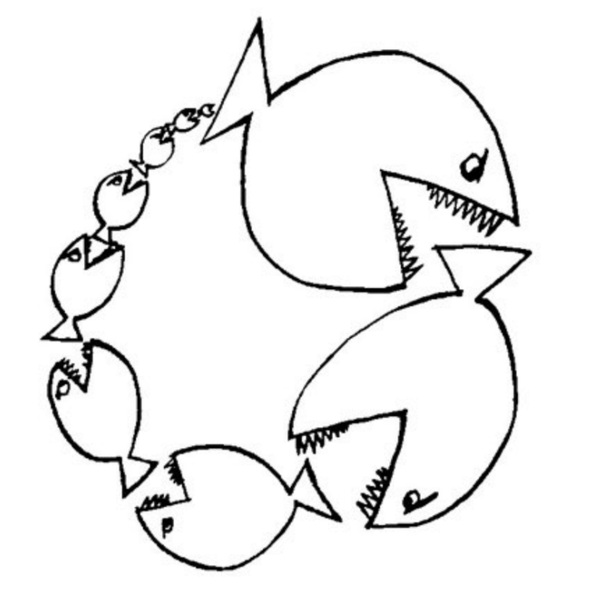

Anyone with a political goal must begin by answering the question: Who rules? Unless you know the answer to this question, you can’t know where to direct your petitions or attacks. For much of the 20th century, the answer many arrived at was that a handful of corporations ruled. There was good reason for thinking this. Corporations determined the conditions of people’s lives, because they made some of the most important decisions about the allocation of society’s resources. This is why a large share of political protests were directed either at corporations, or at government authorities with the goal of getting new regulations imposed on corporations. The battles and debates over how corporations ought to rule constitute the subject of Kyle Edward Williams’s bold new book, Taming the Octopus: The Long Battle for the Soul of the Corporation.

Williams defines the corporation as “a cession of government power.” The corporate form, he reminds us, only exists at the behest of the state, which remits some of its own privileges to the corporation. A corporation receives a charter, a sort of binding constitution, from a state government. This permits the owners of the business to be separated from the business itself, which means that if the corporation is sued or goes bankrupt, its owners are not liable for its debts, and the corporation can survive beyond the lifetimes of any of its owners. It also enables the directors to issue shares on a stock exchange. The ownership of a large corporation is distributed across millions of shares owned by hundreds of thousands to millions of people, many of whom hold their shares by way of a managed retirement fund. Traditionally, company policies are under the control of a vast structure of salaried managers. This makes a corporation completely different from the kind of entrepreneurial business that the theory of capitalism was built on. Instead, it is more like a bureaucratic state, which sustains a small nation’s worth of employees, managers, and investors.

There are other features of corporations that bend the classical definitions of capitalism. The corporate structure enabled firms to grow far larger than proprietary businesses ever did. As they grew, corporations brought functions that were formerly secured by contracts into their own structures. For example, instead of buying fan belts from an independent manufacturer, an automobile corporation could acquire the means to make its own. This meant that less and less of the process of making a car involved market exchanges. Instead, it involved the planned mobilization of resources under the control of a single entity.

Moreover, large corporations were able to escape, to an extent, the laws of supply and demand. Even after the most egregious trusts were broken up and new anti-monopoly laws enacted, corporations retained, and still do retain, a significant power to set prices above the levels that would exist in a perfectly competitive market. The heterodox economist Gardiner Means, and the populist lawmaker Estes Kefauver who popularized his ideas, called this “administered pricing.” The more neutral term is “market power.” Once a corporation was big and established enough, it was able to shape the market as much as it was shaped by it.

Recognizing these features of corporations, many different people over the years came to the conclusion that corporations enjoyed a level of power and permanence that made them more like governments than businesses, and that they therefore ought to take on government-like responsibilities. Both activist critics and paternalist CEOs took this position, and both groups are colorfully accounted for in Williams’s book. There were the “business statesmen” of the 1950s and ’60s, like IBM boss Thomas Watson Jr., whose startlingly un-capitalist-sounding philosophies were reflected in journals like the Harvard Business Review. Later, there were groups like Detroit’s Freedom, Integration, God, Honor-Today (FIGHT), which acquired shares in Eastman Kodak to issue resolutions demanding the company hire more poor black workers. Ralph Nader would later pursue a similar strategy targeting General Motors. Lyndon B. Johnson’s National Alliance of Businessmen expanded the kind of corporate social policy sought by FIGHT, enrolling CEOs of large companies in an effort to fight poverty through job training and hiring. Then there was the late-Vietnam-era movement to divest from companies that harmed the environment or manufactured war materiel, which gave rise to the practice of companies disclosing their positive social contributions to investors.

At the same time, there was a counter-movement, composed of corporate raiders and libertarian economists, as Williams also documents. We are accustomed to identifying both of these groups with the 1980s, but Williams traces their history back earlier, showing how they bided their time during the golden age of the New Deal order. For example, he tells the story of Louis Wolfson, a financial “junkman” who presaged better-known figures like Carl Icahn and T. Boone Pickens. In a period when many saw corporations as bureaucratic institutions devoted primarily to the production of goods for steady profits and secondarily to social functions, Wolfson saw them only as objects of speculation. His modus operandi was to buy inefficient companies and either reorganize them to enhance their profits or simply sell off their assets or disburse their cash reserves to shareholders, not least himself.

Wolfson’s exploits appealed deeply to a man who emerges as one the main characters of Williams’s book, an economist named Henry Manne. Today, Manne is the possessor of a minute Wikipedia article, but according to Williams, he is one of the most important figures in the rise of neoliberal theory, on a par with Milton Friedman. Manne studied at the University of Chicago under Aaron Director, a pioneer of what came to be known as Chicago School economics. From Director, he absorbed the philosophy of economic libertarianism: that the competitive market is the only means of disseminating the necessary information for allocating resources to their most useful ends. He saw raiders like Wolfson as agents of competition who might roll back the anti-market effects of the corporate revolution. His article “Mergers and the Market for Corporate Control” argued that the separation of ownership and control that characterized the corporate economy need not prevail. If a manager ran a company inefficiently, the company’s share price would decline, and the company would be vulnerable to a takeover bid by someone who would improve efficiency and raise the share price. In this way, the threat of corporate raids constituted protection for the shareholder, guaranteeing that the owners wouldn’t be ignored by the controllers of the corporation. It reintroduced market pressure into an economic system that had grown flabby and bureaucratic.

The story of how the golden age of the corporation came to an end has often been recounted. In the 1970s, a combination of stagnation and inflation challenged the credibility of reigning economic policy. A sharp rise in interest rates under Federal Reserve Chairman Paul Volcker, intended to curb inflation, changed the financial climate to favor quick returns over slow-to-appreciate investments in industrial business. A new generation of corporate raiders arose to prey on distressed industrial firms, and Chicago School economics took over academia. Shareholders went from being put-upon to pampered, as the idea that share value was the only meaningful reflection of a company’s success took hold.

Out of the ashes of the old, integrated industrial firm, a new kind of corporation would arise, typified for Williams by the example of Nike. While the classic corporation sought to bring every part of the production process under one roof, Nike reverted to a 19th-century style of doing business, contracting production out to sweatshops abroad and retaining only a small core of design staff. As the corporation shed its bureaucratic functions, it became harder to imagine it taking on government-like functions. As Williams recounts, Nike’s promise to raise its minimum hiring age at its far-flung contracted apparel plants to 16 was considered a significant act of social responsibility. This was a far cry from the kind of positive social function corporations aspired to fulfill in the era of industrial statesmanship. The corporation no longer seemed to exercise the same power of ruling, or bear the same responsibility for ruling justly.

“Once a new elite is in place, its members become rulers.”

So, who, if anyone, assumed rule in the wake of the corporation’s hollowing out? An answer is suggested in the last chapter of Williams’s book, titled “Larry Fink: President of the World.” A few financial firms now hold large enough portfolios that they can be said to control the market, rather than being controlled by it. Williams cites experts who predict that within 20 years, 40 percent of the shareholder votes of all companies in the S&P 500 may be in the hands of just three large investment firms. Like the corporation before them, these firms have begun to transcend the identities of mere market players and embrace the prerogatives and responsibilities of rulers. Larry Fink, the CEO of BlackRock and the pioneer of environmental, social, and governance (ESG) investing is the symbol of this new economic paradigm. His firm has combined the activist shareholder strategy of the 20th century underdogs with unprecedented institutional power, effectively pushing large sectors of private industry toward more green and socially activist policies. “And what about profitability?” Williams asks. “Well, what about it? When mega institutional investors direct management policy and plan financial strategies according to ESG priorities, their outsized influence shapes (or distorts, if you like) markets.”

It seems that, unfortunately for the Henry Mannes of the world, we are heading back toward some sort of a planned economy. I suspect this is an inescapable condition. Competition is a temporary interlude through which one set of dominant elites is replaced with another. Once a new elite is in place, its members become rulers. The negotiation of a compact between subject and ruler is the business of politics. In order for this business to begin, we must first know that we are ruled. Kyle Edward Williams’ book is an excellent vehicle for clarity on this point.