In 1988, the gay author and activist Larry Kramer published an open letter to Anthony Fauci, who in his role as the director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases—a position he held until last year—was the government official responsible for overseeing most AIDS research. From the opening paragraph, Kramer pulled no punches in his attack on Fauci’s perceived slowness in testing and approving the sale of drugs to fight AIDS. He called NIAID officials “monsters,” “idiots,” and “murderers,” and went on to compare Fauci to Adolf Eichmann. More than just angry, Kramer’s tone was downright apocalyptic. He referred to AIDS as “the worst epidemic in modern history, perhaps to be the worst in all history.”

What’s most remarkable about this document, other than its vitriol, is the fact that it turned out to be the beginning of a beautiful friendship. After its publication, Kramer and Fauci began to correspond and later got together regularly over the decades. “We loved each other,” Fauci told The New York Times after Kramer died in 2020, just a few months after Covid had placed the NIAID director in the spotlight once more. In the interview, Fauci fondly recalled that Kramer would regularly denounce him to the press but then tell him privately he “didn’t really mean it. I just wanted to get some attention.” Beneath their public antagonism, the two men had a shared interest in keeping AIDS in the public eye, since this would increase funding for drug research.

The bond between Kramer and Fauci exemplifies a broader transformation in the relation of activism to science and the pharmaceutical industry. Increasingly, Big Pharma has come to cast its pursuit of profits in humanitarian language borrowed from activist groups, enlisting apparently radical activists as partners and turning to them for rhetorical support. The AIDS crisis was a pivotal chapter in this process, and the way it played out set the stage for later developments, from the Covid pandemic to the recent explosion of transgender identification.

AIDS was first observed among gay men in the early 1980s. Its cause was initially a mystery, but in 1984, Secretary of Health and Human Services Margaret Heckler held a news conference announcing that the probable cause of AIDS had been found: It was an infectious disease caused by a retrovirus, eventually labeled Human Immunodeficiency Virus, or HIV. At the time, Heckler expressed optimism about the prospects for treating and even curing AIDS, predicting a vaccine would be available in a few years.

This prediction proved wide of the mark. By the late ’80s, treatments had been developed, but there was no cure in sight. Meanwhile, tens of thousands had died of AIDS, the vast majority of them gay men and intravenous drug users. Many believed the Reagan administration wasn’t doing enough to address the crisis owing to homophobia. It is true that the president himself declined to mention AIDS in his speeches, but as a matter of policy, the activist narrative wasn’t quite accurate. In reality, the federal government was starting to move at an unprecedented speed.

In 1987, a year before Kramer penned his j’accuse against Fauci, the first ever drug to fight AIDS had been approved for sale after the fastest trial in Food and Drug Administration history. Azidothymidine, or AZT, was a failed cancer drug repurposed to fight the new disease. The double-blind trial that led to AZT’s approval was controversial: Some patient advocates thought it unethical to run a trial with a placebo arm at all; in their view, AIDS patients were in such a desperate state that they should all have been given access to any drugs that might have helped them. Meanwhile, other critics pointed out that the evidence was inconclusive at best, and that AZT was a highly toxic substance that might well do more harm than good.

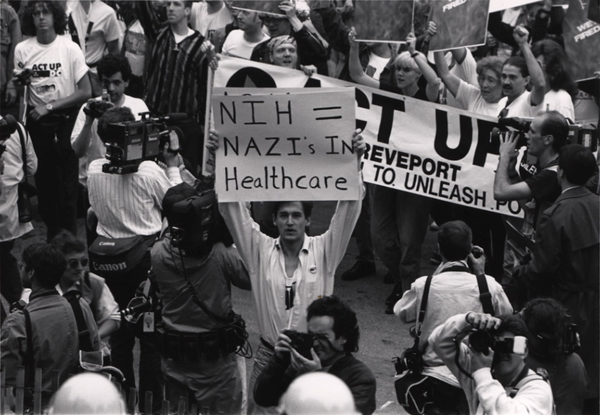

The same year, Kramer formed the AIDS Coalition To Unleash Power, or ACT UP. Born partly out of dissatisfaction with AZT, ACT UP aimed to pressure the federal government to develop and approve better drugs to fight AIDS. The group got its start in New York City, but chapters soon sprung up in other cities around the country and abroad. ACT UP adopted the disruptive tactics of earlier New Left social movements: Its members would picket federal buildings, stage “die-ins,” block traffic, and even pelt government officials with condoms.

ACT UP’s most potent symbol was an upside-down pink triangle with the words “Silence = Death” printed underneath. In the activists’ view, Reagan’s notorious reluctance to pronounce the word “AIDS” in public was a kiss of death, and they were determined to marshal their rage to break this silence. With the pink-triangle iconography, ACT UP linked the AIDS crisis to the Nazi persecution of gays; Kramer and others frequently claimed that the government’s inaction on AIDS amounted to a willful policy of genocide (hence his comparison of Fauci with Eichmann).

As confrontational as it was, ACT UP was also adept at making alliances. It hailed from the far left, but its goals weren’t always traditionally leftist ones. In fact, the movement’s rallying cry “Drugs Into Bodies” aligned it with a conservative push to deregulate the pharmaceutical industry, conversely pitting it against liberals who favored regulation and consumer protection. Moreover, despite ACT UP’s radical aesthetics, much of the medical and scientific establishment wound up finding the group’s message congenial. In 1990, at the Sixth International AIDS Conference in San Francisco, Fauci spoke highly of AIDS activists and exhorted his colleagues to take them seriously. For this, ACT UP members gave him a standing ovation.

ACT UP’s embrace of Fauci points to a curious contradiction within the movement. Its founder, Kramer, and most of its members were gay men who sought to remove the stigma surrounding AIDS as a “gay disease.” However, in the early days of the crisis, Fauci had arguably done more to whip up homophobic hysteria than any other public figure. In 1983, he wrote an editorial for the Journal of the American Medical Association suggesting AIDS could spread through “routine close contact.” Nothing could have been further from the truth: HIV would turn out to be one of the least infectious agents ever discovered. Fauci himself would soon disavow the claim, but the damage was done: His claim initiated a prolonged fear campaign.

In 1985, Life magazine ran a cover story under the headline: “Now No One Is Safe from AIDS.” Two years later, Oprah Winfrey quoted experts on her show to the effect that 1 in 5 heterosexuals might die of AIDS in the next five years. At the time, Oprah was about the most sympathetic ally gay men had in mainstream media. She wasn’t trying to spread homophobia—just the opposite. The assumption seemed to be that making AIDS a universal concern would destigmatize it.

In practice, however, this sort of hyperbole had the opposite effect, stoking fear of those seen as most likely to spread the disease. Terrified parents rallied against admitting HIV-positive students to their kids’ schools. Their fears were misplaced, but understandable. Many in the public-health establishment and the media had been telling them that AIDS was likely to spread to the general population and kill millions. It’s difficult to destigmatize a disease while simultaneously claiming that soon everyone will be dead from it.

The simple fact is that AIDS was a tragedy for gay men and other well-defined risk groups but never posed a serious danger to the general population. That was the message of The Myth of Heterosexual AIDS, the controversially titled 1990 book by the conservative journalist Michael Fumento. The author’s strident tone drew activists’ ire and prompted a concerted campaign to get the book banned from bookshops and libraries. But his underlying claim—about the minimal risk posed by AIDS to the general population—would win the grudging assent of the health establishment later that decade.

“The gay community and the general public would have been better served by more sober rhetoric.”

Even so, activists like Kramer continued to work with public-health officials like Fauci to portray AIDS as a universal catastrophe, possibly the worst plague of all time. The fear campaign worked in terms of getting maximum attention and research funding, but it also took a toll. In retrospect, both the gay community and the general public would have been better served by more sober rhetoric, which could have allowed gay men to rationally assess their own risk and reassured the vast majority of society that they had little to fear.

Decades later, Fauci and the public-health establishment would repeat the same mistake with Covid, portraying the disease as a universal threat, despite the fact that it was overwhelmingly a risk for the frail and elderly. In both instances, the effect was the same: to promote dependence on the public-health apparatus and expand the consumer base for novel pharmaceuticals.

In its activism and agitation, ACT UP was often fighting against inherent biological limits as much as governmental policies. No amount of rage and public awareness could by themselves cure a disease. To this day, despite decades of well-funded research, there is still no vaccine for HIV-AIDS. The drugs have gotten more sophisticated, but in principle, the treatment remains the same as it was with AZT: AIDS is still treated as a chronic condition to be managed with antiretrovirals.

With the appearance of Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis, or PrEP, in 2012, it became common to prescribe antiretrovirals not just for AIDS patients, but also as a daily preventive measure for healthy sexually active gay men. This trend of medicalizing the healthy hasn’t been unique to homosexuals, of course. As the physician and critic of medicine Seamus O’Mahony has written, “Pharma’s single greatest idea was to move its focus from the sick to the well, thus creating vast new markets of ‘patients’ requiring lifetime treatment with drugs.” For example, healthy people can be redefined as being at risk of future disease based on measures like blood pressure or cholesterol and then prescribed medication they must take for the rest of their lives to keep the risk at bay.

The increased medicalization of everyday life in recent decades hasn’t been a purely top-down process. However unwittingly, AIDS activists played a part in bringing it about. ACT UP provided a model for patients organizing themselves into a political constituency to raise awareness and demand drugs for their condition. Pharma is an enormously powerful industry, but by funding patient-support groups, it can present itself as the voice of the powerless.

During the Covid pandemic, many activists demanded that medicine and public health be accorded massive power over our daily lives. Notable among them was Yale epidemiologist and public intellectual Gregg Gonsalves, a veteran of ACT UP. As a young man, Gonsalves spoke of the need for activists to prod science in the right direction on AIDS research. More recently, he became a vociferous advocate of mask and vaccine mandates to fight Covid.

But nowhere is ACT UP’s legacy more apparent than in the relationship between contemporary transgender activism and transgender medicine. In this politically charged domain, the division between science and activism has broken down almost completely. Activists have managed to get the medical establishment to adopt the so-called affirmative model for gender dysphoria. According to this model, if patients experience distress about their secondary sex characteristics, the role of medical professionals is to affirm them as having a transgender identity and put them on path to hormones and surgeries.

“In their rhetoric and style, trans activists bear a close resemblance to ACT UP.”

In their rhetoric and style, trans activists bear a close resemblance to ACT UP. Both groups have argued that withholding access to experimental drugs amounts to deliberate murder, and the ubiquitous talk of “trans genocide” echoes ACT UP’s rhetoric from decades ago. Trans activists, like AIDS activists in their day, see themselves as a radically oppositional force, but their demands happen to coincide with the interests of a pharmaceutical industry always seeking out new groups of lifelong customers and novel rationales for loosening regulatory oversight.

In one crucial respect, trans activism goes well beyond ACT UP’s work. While Kramer and others exaggerated the dangers of AIDS to the population at large, it was certainly true that many people were dying or desperately sick of the disease in the group’s heyday. By contrast, trans activists’ claims about looming death are almost entirely a rhetorical tactic. We see this, for example, in the routine claim that dysphoric youth will all kill themselves if they aren’t allowed to transition. As a statistic, this is a fabrication, but suicidal ideation is contagious; by endlessly repeating it, activists make it more likely to be true. The assertion is better understood as a threat than a statement of fact.

With trans rights, the merger of Big Pharma and left-wing activism has become fully autonomous, creating a new minority with a lifelong medical condition in need of ongoing interventions, to be supplied by some of the wealthiest and most powerful oligopolies on earth. It’s debatable whether this is a culmination of the legacy of ACT UP or a deviation from it. Regardless, in pressuring the medical establishment to meet their demands, activists have become the shock troops of a predatory industry only too happy to expand its customer base.