Javier Milei’s triumph in the first round of the Argentine elections last year—the first of three that make up our tortuous process of electing a president—provoked not just shock, but confusion. Immediately, WhatsApp threads were bursting with different versions of the same question: Was he “far right”? Or was he something more bizarre—the first libertarian candidate in the world with a chance to win? The question was—and is—far from foolish. Milei presented himself as a central part of a new right-wing international, expressing solidarity with world leaders like Donald Trump and Brazil’s Jair Bolsonaro. Everyone was happy then: The global right had a new idol in the Global South to celebrate, and the left had a new mini-Trump to combat. In an era of flat politics and memes turned into presidents, that would seem to be enough.

But things aren’t that simple.

The category of “far right” suffers the same fate as the concept of neoliberalism—both are ideas that, in their effort to explain everything, end up explaining practically nothing. This isn’t just a problem for analysts and scholars: It is an eminently political challenge with practical implications. In Argentina, much of the progressive intellectual elite—most of them ideological supporters of Kirchnerism, the center-left formation that governed for 16 of the last 20 years in Argentina—prefers to think that Milei came from outer space, an alien virus that arrived from abroad and ended up contaminating the minds and souls of a vulnerable nation. Milei’s personal eccentricity, of course, helps: An alien who talks to dead dogs, straight out of a Phillip K. Dick novel, surely can’t be a standard for anything. At this point, the concept of “far right” is a way to close the debate, rather than open it—apart from being very convenient because of how exculpatory it is. If this is a political pandemic, a zeitgeist of global discontent, then no one is responsible. No one can be blamed for an alien invasion. We are innocent.

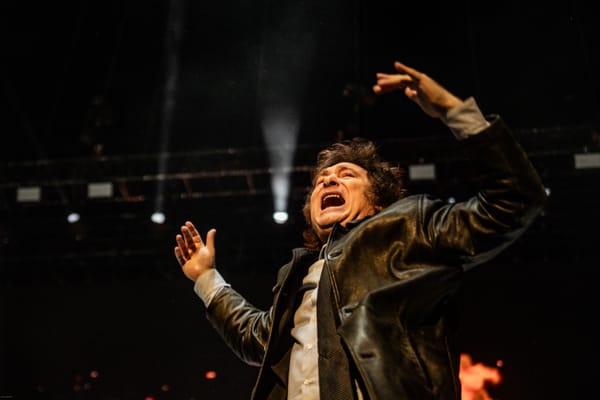

Being so easy to caricature, Milei’s persona often clouds vision and inhibits understanding, and that’s the reason why it is so comfortably tempting not to probe beyond his wild public performances. But as relevant as his ideological obsessions are, there is also what we could call the uses of Milei. Unless we assume that millions of Argentinians suddenly became fanatical devotees of Ayn Rand and Milton Friedman, we must ask: What did the people who voted for him want to do with him—what sort of system did they want to blow up, and why?

In 1994, the German historian Ernst Nolte published The European Civil War, 1917-1945: National Socialism and Bolshevism. The book was heavily criticized at the time for putting forth a controversial thesis. The claim, simple and historically verifiable, was that first Mussolini’s Fascism and then Hitler’s Nazism were a reaction, a global and comprehensive response—symbolic, metaphysical, and ideological—to the challenge posed by the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917, amounting to a reverse Leninism that used the same methods as their rival: mass mobilization, the single party, permanent civil war as a mode of governance, and state terror. Not a counterrevolution, but a revolution of its own: the black international against the red international. The discussion around Nolte’s book had to do with what other historians thought was a relativization of the intrinsic and incomparable evil of the Hitlerian regime, which seemed to have emerged from the void. The idea that 20th-century fascism had somehow gotten started by picking up the gauntlet that Lenin had thrown on the table implied, for these critics, an unbearable moral equivalence.

Whatever you make of Nolte’s thesis as to Europe, you could say that an equivalent relationship was established between Milei and his supporters and Kirchnerism, the movement that hegemonized Argentine political life for two decades after the great crisis of the Washington Consensus in 2001. Between the North and South, there is a relevant difference at this point: The first decade of the 21st century, in Latin America, witnessed a near-unanimous turn to the left. In fact, these were perhaps the most relevant left-wing attempts to govern in the world after the fall of the Berlin Wall. There were many variations, of course: from the European-style social democracy of Michele Bachelet’s Chile to Evo Morales’s indigenism in Bolivia; from Hugo Chávez’s “Bolivarian Revolution” in Venezuela to Lula’s social state with fiscal responsibility in Brazil; from the moderate Broad Front in Uruguay to the Kirchnerist revival of Peronism in Argentina.

But speaking broadly, we can refer to an easy first decade of leftist rule in the region, fueled by a boom in exportable commodities and trade with the rising Chinese giant; and later, a more difficult and embattled second decade after the 2008 crisis, in which many left-wing governments began to find it much more difficult to sustain the levels of consumption and relative socioeconomic well-being achieved over the previous decade. This is the transition from Lula to Dilma Rouseff, from Chávez to Nicolás Maduro, and from Néstor Kirchner to his wife, Cristina. Sequels are always worse. The new right-wing forces in Latin America came to power after these processes, and that partly explains their differences with their Northern counterparts, which are generally more statist and protectionist, in addition to being socially conservative.

Peronism, with its social-Christian ideology and workerist origins, has taken on many forms since its birth in 1945. It was Rooseveltian in the 1940s and ’50s, left-wing and revolutionary in the 1970s (at least in an important fraction of the youth wing of the movement), and even neoliberal in the 1990s under Carlos Menem. After the 2001 economic crash widely blamed on Menem’s economic heterodoxy, the Kirchners restored a more traditional Peronist politics and tried to bring together two previously separate agendas: the agenda of the traditional workers and the new poor created by the crash, and the progressive agenda of the urban middle sectors, linked to the defense of human rights, gender equality, and new political rights in general.

“Milei is a consequence, not a cause.”

The synthesis held up during the commodity boom. But then the country was plunged into an escalating economic crisis: Since 2011, Argentina has seen low growth, sustained and dramatic inflation, and general deterioration of all socioeconomic variables. As a result, the class alliance that held up Kirchnerism began to crack up, and the gap between the two agendas widened. Cristina Kirchner’s new leadership went all-in on a culture war—inane pronoun proposals galore—while inaugurating a new and suffocating personality cult. A new woke Peronism was born, with populist practices and a will for regeneration, and strong influence in the urban middle sectors and universities. Peronism gentrified while it radicalized, organizing a new “militant state” around a new youthful, middle-class base, and carrying out a bloodless and administrative cultural revolution against the old, generally more moderate Peronist cadres and against anyone considered insufficiently loyal to the Kirchnerist regime. In this era, a new nomenklatura of officials and professional revolutionaries is also born, the Animal Farm of Peronism, the caste against which Milei’s libertarians would later position themselves. No single force was more responsible for the demolition of the political center in Argentina or for the failure of Alberto Fernández’s government, than this Kirchnerism. Milei is a consequence, not a cause.

Libertarian ideology imitates this process, but in reverse. Where Kirchnerism proclaimed that “the state will save you,” libertarians respond: “The state kills you.” When Kirchnerism raises the Palestinian flag, Milei and his disciples raise Israel’s. They embrace the codes and methods of the enemy’s culture war. The failure of Mauricio Macri’s center-right government, which sought its political references in Barack Obama and Emmanuel Macron, closed the circle, convincing many voters that the cure must be as radical as the disease, through the invention of an anti-Kirchnerism just as populist, just as militant, and just as post-truth.

The earlier polarization of Kirchnerists and Macrists also had a cynical side. A political system that served only to organize competition between left and right elites came to believe that Milei could be their useful idiot. Milei was extensively financed and supported by Kirchnerists and Macrists, the former because they thought that this would harm the mainstream center-right, and the latter because they thought that Milei was pushing the boundaries of ideological taboos they themselves had not dared to break. The system wanted to make use of Milei, with the paradoxical result that the Argentine electorate ended up using Milei as a tool of punishment and destruction wielded against that same order. Milei is a poor answer to a fair question. He isn’t an alien virus from outer space, but a Frankenstein who escaped from the laboratory, and the name of a great—and maybe in the long run necessary—reset.

At night, when progressivism looks in the mirror, Milei is what it sees.