Union members are far more willing to support Republican candidates than are the elected leaders of their labor organizations. This shouldn’t be a surprise. Union officers take a more institutional perspective on candidate selection: A candidate who is hostile to collective bargaining isn’t going to get their nod. Still, institutional labor isn’t as uniformly Democratic as is often assumed. Law-enforcement and building-trades unions regularly endorse the GOP at the state level. In 2008, the International Association of Machinists took the unusual step of issuing a dual presidential endorsement of Hillary Clinton and Mike Huckabee, in recognition that Republicans formed a sizable portion of its members. Still, you can count the number of congressional Republicans with strong labor backing on one hand.

Are there reforms that could make unions more open to GOP candidates while simultaneously making those candidates more pro-union?

For a split second in the first weeks of the Trump administration, we had a glimpse of a possible future. Presidents of building-trades, industrial, and transport unions, nearly all of whom had endorsed Donald Trump’s Democratic opponent, were invited to the White House. Trump was on board with steel-import tariffs that unions had been advocating for years. But the bonhomie didn’t last. While the Trump administration’s trade policy was more in line with the old-school labor Democrats of yesteryear than with the contemporary Republican Party, there was no institutional program to change labor policy through presidential appointments. Officials at the National Labor Relations Board and other important bodies might as well have been appointed by the Heritage Foundation and the American Enterprise Institute.

“Unions could be more creative in how they manage political endorsements.”

While the Trump White House was considering making a serious bid for labor support, this was a difficult dance, involving parties not accustomed to dancing together. Perhaps it could go better next time. One way to make the dance less awkward in the future is for labor and the GOP to start seeing each other as possible allies. Unions could be more creative in how they manage political endorsements. Republican candidates, for their part, could make good on the GOP’s rhetoric about transforming the party into a vehicle for the multiracial working class—by supporting pro-union reforms.

The process by which unions endorse candidates can be rather byzantine. There is no law controlling how this is done; it is entirely an internal process of each union. To complicate matters further, state or regional labor councils make endorsements that don’t always correspond with those of their member unions. For example, in my own state, the Maryland State and District of Columbia AFL-CIO endorsed Democrat Ben Jealous for governor in 2018, while the Republican incumbent, Larry Hogan, received the backing of the Laborers’ Union, the Firefighters Union, and the Plumbers and Pipefitters Union—all AFL-CIO affiliated unions themselves.

Typically, for high-profile public office, the endorsement process will involve polls of members, reviews of questionnaires candidates submit to the union, and interviews with candidates. The national governing body of the union will then vote. For lower-profile offices, an endorsement could be as simple as a district officer making a decision.

Sometimes, the members and even leaders of locals don’t support the national union’s endorsement. What can they do? Again, there is no single answer. Some unions have an endorsement process in which some affiliates openly dissent. For example, two bargaining councils of the American Federation of Government Employees endorsed Trump in 2016 and 2020, while the national union endorsed Hillary Clinton and Joe Biden, respectively. A separate endorsement by a council had never happened before, but there was nothing to prevent it.

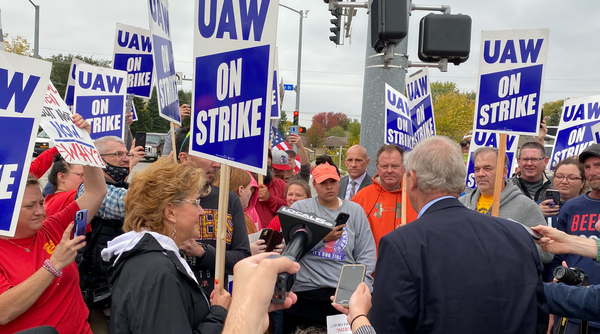

The United Auto Workers, by contrast, keeps a tight grip on endorsements. In that union, locals are constitutionally required to affiliate with state and regional political bodies called Community Action Program Councils, composed of elected officers, which make endorsement decisions. UAW regional bodies must then approve recommendations made by councils before they become official. A UAW description of the process acknowledges that members often disagree with the union’s endorsements:

Sometimes UAW members get sidetracked by issues or positions that are not work-related but that appeal to strong personal feelings or beliefs. Union members need to consider where their priorities and interests lie—with the union that is looking after their physical and financial well-being, or another interest that may be part of a plan to divide working people for the purpose of winning elections … When workers are divided by cultural ‘wedge issues,’ our opponents win.

The UAW does great work, but this is a telling remark. It presumes that workers may live in a flourishing culture, or have a justly run workplace in a just economy, but they can’t have both. Put another way, members are asked to totally subordinate their legitimate concerns about cultural questions—and culture-adjacent political-economics ones like, say, immigration—to the political calculations of the national UAW. But shouldn’t the working class be able to express itself on the full range of issues?

Some locals might have the ability to make individual local endorsements, but either don’t consider it, or are pressured not to. Even if doing so would not violate the union’s constitution, there could be practical repercussions for being perceived as politically disloyal. Could legislative changes provide for more local autonomy in making such decisions? Probably not. The National Labor Relations Act and the Labor Management Reporting and Disclosure Act are expressions of Congress’s power to regulate matters affecting interstate commerce. Political endorsements made by unions are another thing altogether. Aside from some potential constitutional problems, a civil authority would have to be charged with policing the process of internal union endorsement decisions. This doesn’t seem tenable.

Absent such changes, both unions and GOP candidates could do things differently. Unions that have complex processes of endorsement ratification could allow for more local autonomy in making endorsement decisions. Restrictive processes effectively impede the creation of a more pro-union GOP. When Republican candidates get union endorsements, they will regard the union as a constituency, rather than an opponent. Indeed, a considerable part of the GOP hostility to organized labor is that it is perceived as part of the Democratic coalition. If that changes, we can envision a Republican Party that opposes so-called right-to-work laws on the grounds that it is legitimate for union security arrangements to enforce duties of solidarity.

Republican candidates themselves need to move past the reflexive anti-union talking points that have been standard fare for well more than a century, and that are really more libertarian than they are conservative. GOP candidates could shift the conversation to an entirely different plane: They could propose labor-law reforms that promote German-style sectoral bargaining. This would simultaneously strengthen labor unions and make union organizing less adversarial.

It’s a classic case of each side waiting for the other to make the first move. Republican candidates complain that the unions are part of the Democratic machine, which is basically true. Unions complain that the GOP is suspicious of collective bargaining and for right-to-work laws, which is also basically true. It has been this way for too long, and we are now in the middle of a political realignment in which the Democratic Party is firmly the party of the professional-managerial class. Republicans and trade unionists need to take the plunge.