There was a moment that occurred a few days before Election Day that few Americans heard about, but I doubt it would surprise them. Kamala Harris was asked by a reporter how she would be voting on Proposition 36 in her home state of California. Proposition 36 involved increasing certain penalties for drug and theft crimes. Unless you’ve been living under a rock, you’ll know that retail theft and open-air drug use have become high-profile issues in the Golden State. Criminal-justice hawks and doves bitterly debated the issue, seeing it as a referendum on whether California would adopt tough-on-crime policies or continue to pursue a more reform-minded approach.

It was the perfect issue for Harris, who started her career in politics as San Francisco district attorney before rising to state attorney general. If there’s anything Harris knows, it’s the debate over tradeoffs between punishment and rehabilitation, public safety and human rights. And yet, rather than launching into a robust defense of the proposition, which would have helped her push back on Trumpian accusations that she is soft on crime, or attacking it, which would’ve been standing on principle against a measure some Californians regarded as draconian and excessive, Harris did the most Harris thing possible: She dodged the question in an inartful way.

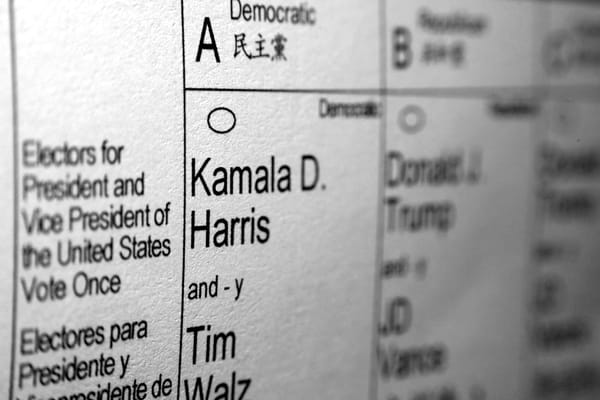

“I am not going to talk about the vote on that,” she responded to a reporter. “Because honestly, it’s the Sunday before the election, and I don’t intend to create an endorsement one way or another around it.” The reply nicely summarized Kamala Harris’s political career, which came to an abrupt end in the wee hours of Wednesday.

It’s hard to say that Harris, aged 60, ever took a bold or courageous stand on anything during most of her political career. The closest she ever came was opposing the death penalty as DA—but come on, she was in San Francisco, not San Antonio. As I wrote in these pages months ago, she was a candidate without convictions.

Despite her party endlessly pronouncing that they are the guardians of democracy, she was elevated to the presidential slot without winning a single primary or caucus—the first such nominee in decades. I was shocked by the democratic backsliding in the party—which began by insiders hiding President Biden’s frail state until late into the summer, then deposing him, and then anointing a successor without even the “mini-primary” some party elders had advocated for.

But maybe I shouldn’t have been surprised. One of the most consistent beliefs I’ve encountered working in and around politics is anti-populism: a belief that the people are fundamentally untrustworthy and need to be guided by elites. This is how vast swaths of professionals working in think tanks, academia, and elected office think about Americans.

Had Americans had an opportunity to pick a presidential nominee for the Democratic Party, it wouldn’t have been Kamala Harris. There’s a reason her frequent remarks about growing up “in a middle-class family” became the butt of online jokes. She was unable to establish an authentic connection to the struggles that people face—and not just economic struggles.

How little emotional intelligence did Harris have to be parading around the endorsements of Liz and Dick Cheney? This was at a time when Muslim Americans, loyal Democratic voters for some two decades, had been watching people of their faith killed by the thousands on their television screens for a year. Unsurprisingly, early data from states like Michigan suggest that Arab and Muslim voters fled from her campaign in droves. (Comically, she had to rework an interview with a Muslim influencer who was prevented from talking to her about the Middle East but who she also awkwardly offended by suggesting that bacon is a spice.)

And what was the upside? Does anybody know any substantial number of voters in this country who were leaning toward Trump before were persuaded by Cheney’s appeals? All of this was obvious to ordinary voters—Democrats, Republicans, and independents alike. People intuitively knew that Harris just didn’t understand policy deeply, nor did she have very strong convictions about how to tackle pressing problems like the economy, the border, or wars overseas. She didn’t know how to talk to Republicans, either, which is why she dragged Cheney—a figure who has zero purchase in the modern GOP—all over the country in a vain effort to broaden her coalition.

“She was a bad nominee because she would have been a bad president.”

Harris’s lack of convictions wasn’t a problem that Democrats could simply market their way out of with coconut memes, appearances with Oprah Winfrey, or Saturday Night Live hits. She was a bad nominee because she would have been a bad president, and anyone not deeply in the Democratic hype bubble knew this. How could someone who was too anxious to do a three-hour sit-down with Joe Rogan manage international negotiations? How would someone who never had the courage to come up with a single bold idea as a senator or vice president come up with solutions to wars in Ukraine or Gaza?

My hope is that Harris’s loss might prompt the Democratic Party to reflect on its own name. Founded by Andrew Jackson and Martin Van Buren as an anti-elite vehicle, the party of what they called “the democracy” is supposed to embrace, well, democracy. That means elevating people to the highest levels of power only after robust debate, fierce competition, and the consent of rank-and-file members.

By installing a candidate without convictions, the Democrats have lost yet another winnable election to Trump—a deeply flawed man whom a capable opponent could have easily overcome. If they want to win again in four years, Democrats need to learn to trust the American people and the democratic process. That means a robust presidential primary and candidates who are fully transparent about their strengths and weaknesses. The Democratic Party lost this election by abandoning democracy. It can retake the White House in four years by learning to love it again.