In early 2018, a graduate school classmate contacted me. Did I know that one of our former professors was up for tenure—the one who’d made a pass at me years ago? Did I remember how upset I’d been when that happened, how I’d come to her, distraught, for advice? Would I join her and others in signing a letter recommending against his being tenured? Other women had stories about him, too, my classmate said. Should such a man be rewarded with such security in his career, to then do with whatever he pleased? Well, but his family, I said. That is what men like him depend on, my classmate replied. That whatever they do, women will extend to them consideration, generosity. Which is never returned.

It had the ring of truth. At the time, the #MeToo movement was gathering momentum. I’d been hearing terrible stories from people I loved, and I’d been thinking of my own stories, and weren’t they all part of the same thing? Wasn’t it time for an accounting? I told her I’d sign the letter. But not long after we hung up, I had doubts. Another feminine impulse, maybe—a sign of having been brainwashed by the patriarchy to protect men and distrust oneself.

Luckily, I had a record: old e-mails and chats. And reading over them, I remembered more. The pass he’d made at me had been a stray remark over online chat, a hypothetical: If only he weren’t married, if only I weren’t so young, if only I weren’t dating his protégé … That’s a lot of “ifs,” I replied, and he dropped it. After that, I was worried that telling my then-boyfriend—the protégé he’d mentioned—about the remark would destroy his relationships with us both. But when I told him, he’d only been disappointed in his mentor, and felt sorry that I’d been put in that position. We all moved on. Not only that: I remained friendly with the professor for years to follow, and asked him to write me letters of recommendation, which he was happy to do.

This was the man whose career and reputation I’d been prepared to tamper with. He’d hit on me, if you could even call it that, once, when I was in my twenties and no longer his student. What adult relationship didn’t have moments that were uncomfortable to navigate? And hadn’t I had an enormous crush on him and fumblingly tried to flirt when I was in his class?

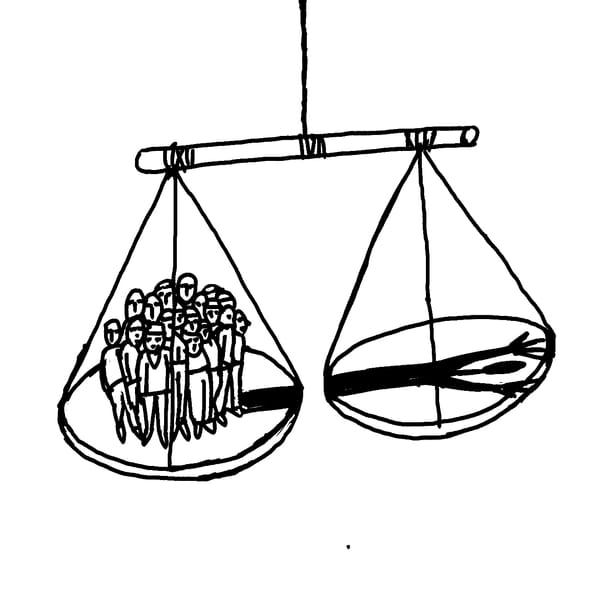

How had those who got swept up in the new quest for justice become so certain about who was good, who was bad, and what they all deserved? The desire for retribution had been elevated at the expense of understanding, mercy, and forgiveness. The reasons for that shift, such as the need to reckon with past abuses of power, weren’t always bad ones. But the urge to protect the vulnerable has morphed into something more troubling, and in the process has turned many young people, especially young women, away from agency and maturity.

In my freshman year at American University, I signed up for a physics course, “Changing Views of the Universe,” taught by Richard Berendzen. I chose it mainly because it looked the least challenging among the options for meeting the science requirement—no lab work or hard math. The class ended up being the highlight of my academic year. Berendzen’s gripping lectures told the stories of visionaries of physics, biology, and astronomy who moved the world forward with their discoveries. For the final term paper, I chose to write about Judaism and bioethics, intrigued by how the faith I’d been raised in tangled with issues like abortion and assisted suicide. I got an A-, and Dr. Berendzen wrote on the top of my paper: “It seems like you learned a lot in the process of writing this.” I had. I was delighted, and got the sense he was too.

“His presidency had abruptly ended with a bizarre and shocking scandal.”

When I was taking Berendzen’s class, I knew he had previously been president of AU, but I didn’t know his presidency had abruptly ended with a bizarre and shocking scandal. In March of 1990, police traced to his office a series of obscene phone calls made to the home of a daycare provider. The woman who received these calls, Susan Allen, was married to a police officer. Fairfax County cops installed a tracer and recorder on her phone and ended up with recordings of dozens of calls from Berendzen, which were, Allen told the Washington Post at the time, “filthy beyond your most horrible nightmares. And 99 percent of it centered around children.”

The scandal made national news, but by the time I arrived on campus a decade later, it seemed to have been forgotten. I only learned about it after the course was over. I was glad to not have known beforehand: I’d have sat there not listening, but trying to square the brilliant man who told us captivating stories from the history of science with his lurid backstory. Even more astounding than the details of the scandal that led to his resignation, it seems to me, is the fact that no one was talking about it 10 years later. I was struck at the time by the understanding extended to him. As the years have passed, his redemption looks all the rarer.

In 1980, when Berendzen became president, American University was a party school. By the time he resigned, it was something else entirely. He was known for working 100-hour weeks and issuing memos on Christmas and New Year’s Day. Under his watch, average SAT scores went up by 200 points and admissions became far more competitive. He was known, too, for schmoozing, making frequent appearances on the DC charity gala circuit and rubbing elbows with the capital’s elite. It paid off: AU’s endowment quadrupled. By the time I arrived in 2001, American wasn’t quite the “Harvard on the Potomac” he had hoped it would become, but it was a respectable university with a student body that was ambitious and politically engaged. Civil-rights leader Julian Bond was a member of the faculty, as were a number of former ambassadors, senators, Guggenheim fellows, and Pulitzer Prize winners.

How had Berendzen gone from facing two misdemeanor charges for deeply disturbing behavior to returning to AU as a beloved professor? “There’s a difference between an excuse and an explanation,” the disgraced former college president told the Virginian-Pilot in 1995. “I provide no excuse for anything. I assume full responsibility for what I did. But there is an explanation. It’s the scientist in me that looks for that.” The explanation he gave was that he had suffered sexual abuse as a child, memories of which had not been suppressed so much as shunted aside in favor of ceaseless activity. All of this had emerged, he said, during treatment at a Johns Hopkins sexual disorders clinic. His doctors there determined Berendzen was not a pedophile and had not hurt any children; the obscene phone calls, they concluded, were a way of “seeking answers to unresolved issues related to his own abuse.”

By then, he was back at AU teaching physics. His return had been bumpy: The reasons for his resignation were not shared with students and faculty at first, prompting outrage, and the Board of Trustees—without consulting the larger AU community—made an initial agreement to buy out Berendzen’s tenure and pay a severance that together amounted to $1 million. Members of the faculty denounced this settlement, and students protested for weeks; Berendzen himself said that he would prefer to come back and teach rather than take the buyout. The university went back to the drawing board, and with input from administrators, faculty, and student leaders this time, agreed to allow Berendzen to return to campus as a tenured professor.

What is perhaps most striking today about Berendzen’s journey is that the majority of AU students were ready to welcome him back. The first three classes he taught were “filled to capacity,” as the Baltimore Sun reported. A sophomore who registered for one of them told the Sun, of the obscene phone calls, “We’re all adult enough to go past that.” Even in the scandal’s immediate aftermath, the campus response had emphasized rehabilitation over retribution. In The Eagle, AU’s student paper, one editorial urged empathy: “Richard Berendzen has been more than willing to seek treatment for his illness, and to help others like him … Rather than turned backs and sideways glances, he deserves our understanding, and perhaps our forgiveness.”

This response wasn’t unanimous. Some students told the Sun they wouldn’t take a class with Berendzen, and Susan Allen, for her part, filed an $11 million lawsuit against him and AU. “Any idea of having him back is criminal,” she said. (The lawsuit was settled for an undisclosed amount.) But enough people were willing to move on that by the time I enrolled in his course in 2001, his prior history didn’t even come up. Berendzen continued to teach at AU until his retirement in 2006; he died in late 2022.

Several factors made this redemption arc possible. Prior to his downfall, Berendzen had generated a tremendous amount of goodwill at the school and beyond. After the scandal broke, he seemed sincerely contrite about the phone calls, and articulate and honest in sharing his own story, the details of which were profoundly sad; he went on to speak out about his experience of abuse in a 1993 memoir, and to advocate for victims. There is also the fact that he didn’t actually hurt children. And for the harm he did do to Allen, he was punished: his reputation tarnished, his presidency terminated, the details of his childhood made public knowledge.

Beyond all these particulars, the fact that Berendzen was granted a second chance in a way that similarly disgraced figures usually are not suggests a prevailing attitude that is far less common today. Consider the sophomore who said that she and her peers were all “adult enough” to move past the scandal. To her, being an adult meant being capable of assimilating both the light and very dark sides of a person, of understanding how someone might come to commit a grotesque act. Judging by the way Berendzen was welcomed back, most AU students in the early ‘90s had a similar perspective.

Last year, Stephen Kershnar, a professor at SUNY Fredonia, was banned from campus after posing questions on a philosophy podcast about the morality of an adult man having sex with a 12-year-old girl. The scandal seemed to result from a symbiosis of right-wing outrage and campus safetyism. Clips of the podcast were first posted to Twitter by the account Libs of TikTok, whose m.o. is inflaming the right with outrageous behavior from progressives, helpfully devoid of context. Subsequently, a petition circulated, demanding Dr. Kershnar be kicked off campus, calling him “directly harmful to a community already dealing with instances of sexual assault and struggles with consent.” SUNY Fredonia’s president called the professor’s comments “absolutely abhorrent.” He is still barred from setting foot on campus, ostensibly for his own safety, but teaches courses online; a lawsuit demanding his return hasn’t been decided.

Kershnar has not apologized for his comments, nor asked for mercy—nor, many might argue, should he, as viscerally repulsive as we may find his “thought experiments” to be. Even before this incident, he was so notorious for his provocations that the flare-ups that arise when some aspect of his work goes viral were nicknamed “Kershnar Cycles.” He offended with words, and as was true for Berendzen, there is no allegation, or evidence, that he ever harmed a minor. Of course, the two stories are not entirely analogous. Berendzen’s phone calls, needless to say, had no conceivable professional justification; Kershnar, on the other hand, was engaging in a version of something philosophical gadflies since Socrates have done: asking questions that violate a culture’s taboos.

“When did college students’ notion of themselves as adults shift?”

The Kershnar scandal is just one recent reminder that it is difficult to envision an act like Berendzen’s being not only forgiven but largely forgotten in today’s campus climate. When did college students’ notion of themselves as adults shift? When did they stop being capable of extending grace to someone who had fallen, and instead become children in need of protection from the fallen—and thirsty for their punishment?

One contributing factor was the elaboration new campus codes regarding sexual harassment set forth under Title IX. Originally enacted by Congress in 1972 to contend with gender discrimination in public-university athletic programs, Title IX was subsequently expanded via court rulings to include sexual harassment and assault. In 2011, Barack Obama’s Department of Education issued a “Dear Colleague Letter” to Title IX coordinators at more than 7,000 colleges, revising how schools should adjudicate sexual assault cases. The letter advised using the lowest possible standard of proof in these cases, as well as allowing accusers to appeal not-guilty findings, and imposing a 60-day limit on adjudications.

By the time Donald Trump’s education secretary, Betsy DeVos, rescinded the letter in 2017, more than 700 lawsuits had been filed by people claiming they’d been wrongly accused of misconduct. The damage was done in other ways, too. The result of the changes to the way Title IX was implemented was to chip away at students’ own sense of resilience and stoke sexual panic on college campuses.

That same year I took “Changing Views of the Universe,” I also enrolled in “Sexuality and Literature.” Our readings ranged from a sonnet cycle by the lesbian poet Marilyn Hacker to the Marquis de Sade’s Philosophy in the Bedroom to William Blake’s Songs of Innocence and Experience. Blake’s dichotomy spoke to me: Increasingly cognizant of my own innocence and naivety—reading de Sade I was astonished to find the past was not staid and proper but brimming with outrageous desires—I was hungry for experience. Even, maybe especially, bad experiences. I wanted to have interesting stories, which meant things would have to happen to me.

We celebrated the end of term with a party at the professor’s house, where he had an original Blake engraving hanging on a wall. I relished being in his home, drinking wine, socializing with my older classmates, playing at being an adult. I felt a similar satisfaction when another professor took us to see Hamlet and then to dinner at a Spanish restaurant—both firsts for me, though I tried not to let on. The same professor also drove me off campus when someone called in a bomb threat, two days after 9/11, and all of AU was evacuated. I’d been in the dorm, in my socks, when security hustled us out onto the curb. She loaned me money to buy sneakers and a Metro pass and sent me on my way. I still owe her a thank you. Back then, there weren’t always clear boundaries between students and faculty, and that often felt good. This idea stands in contrast to the recent emphasis on the need for people, particularly men, to learn boundaries.

It could be that AU students felt they were exercising their own power when they took to the quad for three weeks to demonstrate against buying out Berendzen’s tenure—but also when they later extended forgiveness to him, chose to sign up or not for his classes, and moved on with their lives. Today, young people seem to fall more often into what the anthropologist Roger Lancaster calls a “poisoned solidarity,” a bond based on outrage and the desire to punish.

It is often said that the “pendulum has swung too far in the other direction”—that the hypersensitive climate on campuses around sex is an overcorrection for a history of neglect, mistreatment, and impunity. I don’t think this quite captures it. The United States has long had a punitive culture, especially around matters related to sex. On our campuses, the expansion of Title IX, followed by the #MeToo movement, may represent only the most recent flare-up. A generation earlier, the 1980s saw the Satanic sexual abuse hysteria and panic about AIDS. Perhaps Richard Berendzen was partly just lucky to have had his scandal unfold during a lull between more inflamed periods of sex panic, at a time when college students wanted to think of themselves as reasonable adults who could discern when to punish and when to forgive.

The world of Blake’s Songs of Innocence, which we read in “Sexuality and Literature,” is that of the protected, unfallen world of children. It’s the one where many young people today wish to remain, where they can be only victims, not aggressors, because they are innocent. Adulthood means living with the guilt of being human. “Turn away no more,” Blake urges in the introduction to the Songs of Experience, the companion volume to Songs of Innocence. At the time I was grappling with Blake’s poems, I wanted to be a grown-up, which meant being able to bear the whole mess of real life.

In ancient Hebrew, the word for mercy shares the same three-letter root as the word for womb. In a sense, to receive mercy is akin to being a baby in utero, experiencing the ultimate protection, closeness, and love. To believers, we are all God’s children. Maybe to grant mercy is to initiate a reversal—to become an adult, to cease being the helpless child and instead momentarily turn the offender into one.

The childish urge to tattle and see someone punished isn’t new. But our capacity to keep on punishing, in the perpetual present of the internet, is. To reason that we’re all adult enough to move past the offenses of the powerful, or the once-powerful now brought low, and to find in ourselves the generosity to entrust them with a second chance, to not allow the often honorable urge to protect the vulnerable to override the possibility of redemption—I believe we can still do that, but our views of the universe, and our ideas of the laws that govern it, must change, as they have so many times before.