Virality—or the possibility of going viral—is the point of all present culture. There is no good or bad, just more amplification or less. Received forms are melted down for the viral ore. Film becomes video; novel becomes screen-shotted paragraph; essay becomes the commentary-generating “piece”; poem becomes a blob of language which no one will ever bother to memorize. The whole becomes fragment; the vision becomes snippet.

More than ever, the collective, webbed mind seems to supersede the individual mind, which is linked to the global cortex by the screen. Reality is hybrid—virtual and physical. It is uncanny. In this metaphysical abyss, our individual subjectivities lie shattered.

***

The artist then, like any prey in any ecosystem, needs a counter-strategy, a way to adapt to this breakdown of demarcation and authority.

***

Contemporary culture and cultural commentary, because it is decentralized, digitized, avatarized, and algorithmic, forces individuals into herds where reductive analysis, hearsay, and cheap sarcasm fuel virality (the take). The take freezes both the imagination and the intellect. The work is always at the mercy of the take—because the take is disseminated instantly and the work takes time.

***

There is no standing apart from the discourse; there is no thinking outside of the Twitter feed. There is no truth that cannot be deconstructed, no vision that cannot be corrupted.

The digital psyche, like Adam in Eden, gives names to things. You are not you: You are the label you are given; your work is the sum of what is said about it; your ideas are reducible to the reaction to them.

***

A simple question: Is there a way to reflect on the spectacle society without becoming spectacle? In an era of viral action and reaction—instant framing, labeling, politicizing (and worse)—can art resist and do something other than participate in the frenzied discourse (when criticism itself has become spectacle too)?

***

I thought, naively, that I wrote a traditional play about a contemporary cultural moment—but standing back from the experience, Dimes Square was something slightly different than a traditional drama: It was a rehearsal of lived reality, an aestheticized mimesis, which allowed people to practice being in Dimes Square.

***

The artist and the art are not separate from, but rather interwoven with, dense networks of reception and receptivity. Just as the consoling notion of an immortal soul floating free of the body gives way to the pressure of acute physical pain, so does the notion that art transcends its origin. The frenzied swarm of digital commentary rapidly disabuses the creative artist of the notion that he freely chooses his projects; the evolutionary pressures of a digital spectacle society, rather, shape his ends—cajoling, cudgeling, coaxing out images, tropes, forms that illuminate dominant aspects of the discourse at any given time.

***

Nathan Fielder’s The Rehearsal isn’t funny because of the originality of its premise, but because of the ruthlessness and inventiveness with which it executes the premise. The Rehearsal is funny because it reveals how automatic, pre-conditioned, and thoughtless our behavior is, and yet, bitterly, how little actually comes naturally to us. The Rehearsal shows us that our rituals are not really rituals, but substitutes for a lost sense of purpose, home, meaning.

***

Our cultural discourse betrays a very elemental, primal anxiety: that representation and the represented cannot distinguish themselves from one another.

***

Kierkegaard, in his pamphlet The Present Age, which he wrote after being mercilessly attacked in the press, provided an apt analysis of the kind of mediocrities who serve as cultural gatekeepers: “Envy constitutes the principle of characterlessness, which from its misery sneaks up until it arrives at some position, and it protects itself with the concession that it is nothing.”

***

I often suspected that people bought tickets to Dimes Square because getting into the play about the scene was easier than getting into the scene itself.

***

Dimes Square, as a concept, is really just this: the idea that the Internet can become a real, physical place. It represents the fantasy that years wasted on the Internet can be redeemed as real experience.

It is not a coincidence that the phenomenon of Dimes Square overlaps with crypto culture because both are predicated on the assumption that one day digital bullshit can be exchanged for something solid and real.

***

Art is a secular means of developing and maintaining a soul, while providing a basis for others to do the same. Being an artist does not mean being a good person or bad person, but it does involve wrestling with the moral experience of being a human being and the attendant feelings of shame, disgust, joy, pleasure, fear. Creativity is a serious business, in this view, and the artist is a kind of general at war with reality and with himself. I’ve come to believe this view is both antiquated and worth defending.

***

Cultural production prepares itself in advance for the “take”—pre-branding itself for easy identification by critic-consumers on the Internet.

Essentially, increasingly, new contributors to culture—because they actually desire and invite the simplistic “take”—lack any artistic pride. The only purpose of the work is to create enough spectacle to generate further spectacle.

***

So much so-called art, transgressive or woke, in reality is advertisement for a lifestyle, and as such, only furthers our alienation by increasing the ruthless competition for spots both in the scene and in various cultural industries. It does not truly want to disrupt, criticize, or change anything or anyone because the status quo is the very thing that gives it meaning.

***

The difficulty now is that there is no nature to hold the mirror up to.

***

The audience increasingly is the artist—commenting on its strategic position within the artistic psyche. The individual mind is a point of access for networked creativity.

***

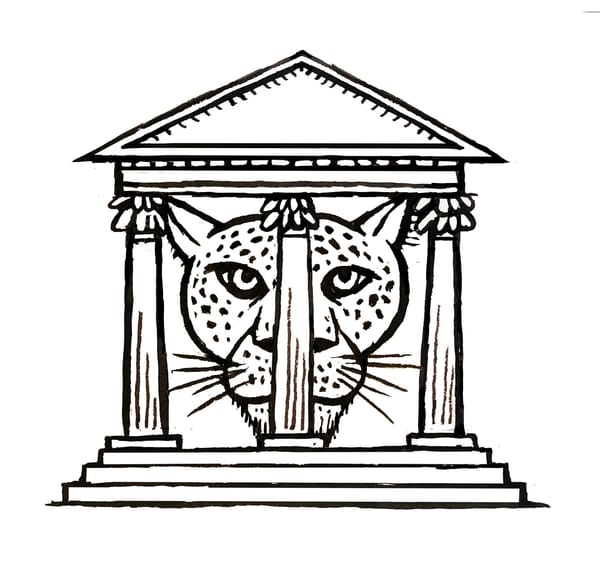

The question then is, in the terms of Kafka’s parable, what does one do about the leopards who have broken into the temple? Should they, in fact, be incorporated into the ritual? Do you try, conversely, to drive them from the temple?

My suggestion would be as follows: Let the leopards have the temple, and then move the rituals to the forests they have abandoned.