Last month, Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell announced a long-awaited cut to the benchmark interest rate, slashing it to 4.8 percent, down from a 23-year high of around 5.3 percent. Just hours later, Brazil’s Central Bank, or BCB, hiked borrowing costs to an astronomical 11 percent, up from an already sky-high 10.75 percent, making the South American nation a hemispheric outlier in terms of monetary policy.

The US Fed, many financiers now agree, took too long to cut rates; the risk now is that further, aggressive cuts may be needed to deter the onset of a recession. Why has the central bank of the second largest economy in the Americas come to the opposite conclusion? After all, if high rates in the United States pose the risk of a downturn, surely the same logic applies in Brazil. The answer given by many economists and pundits is that inflation in Brazil is still too high. By raising borrowing costs, decreased demand will result in lower prices—or so the theory goes.

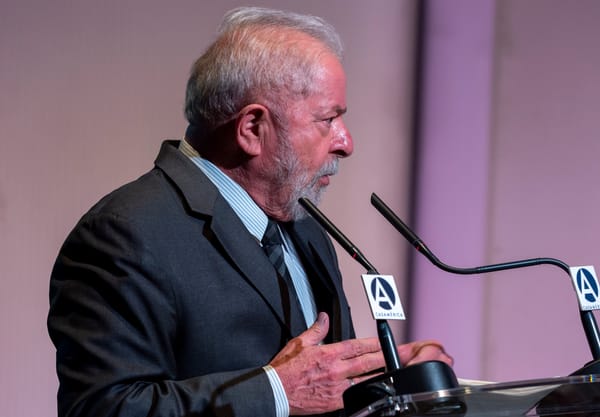

One of the staunchest critics of this approach has been President Luiz Inácio Lula Da Silva, known popularly as Lula. Since assuming office last year, Lula has roiled markets by committing the unspeakable crime of denouncing the BCB’s stratospheric interest rates. His reasoning is that recent inflation is the result of supply-chain disruptions following the end of the pandemic, meaning that price will adjust downward regardless of monetary policy. And indeed, save for East Asia, inflation followed the same pattern, spiking in 2021 and 2022 and beginning to stabilize or decline last year.

In Brazil, inflation peaked at 9 percent in 2022 before stagnating around 4 percent in 2023 and 2024, in line with where it stood in 2019, when the interest rate was almost half the current 11 percent. Nonetheless, economists who support maintaining higher rates claim that debt and inflation remain too high, and blame government spending. True enough, Brazil tends to run large budget deficits—7 percent in 2024—with the debt-to-GDP ratio at around 80 percent. Government spending, however, made up only a small fraction of the country’s deficit. Indeed, the Lula administration has adhered to a 2025 zero-deficit target since coming into office, although the target only applies to the primary deficit, meaning spending that excludes interest payments. As of this writing, the primary deficit is expected to hit a modest 1 percent of GDP in 2024.

The reality is that most of Brazil’s alleged reckless spending is coming from its own central bank, given that around 90 percent of the country’s deficit consists of interest payments. Between 2016 and 2024, Brazil held an average primary deficit of just 1 percent of GDP. But because the central bank has maintained such stratospheric interest rates, curbing total spending has become virtually impossible. In effect, central bankers have extorted elected officials into reducing discretionary spending by ballooning total spending via interest.

Brazil’s economy is highly dependent on the sale of commodities. The global commodity price collapse in 2014 brought about a severe recession, followed by a period of abysmally low growth before the pandemic. It’s no wonder, then, that debt rose to 93 percent of GDP between 2014 and 2019, up from 58 percent. Making matters worse, Brazil’s leaders looked to the European Union for inspiration amid the economic crisis of the 2010s. The conservative administrations of Michel Temer (2016-2019) and Jair Bolsonaro (2019-2022) rolled out an austerity playbook not unlike that inflicted by Brussels on Southern Europe. Social spending was constitutionally capped, and a privatization campaign targeting everything from airports to pensions squeezed what little the Brazilian state already offered its citizens.

Policymakers also curtailed increases to the minimum wage on the grounds that it would fuel higher prices. As a result, working-class wages fell to historic lows, with Brazil’s minimum wage now among the lowest in the hemisphere. Finally, the central bank resolved to maintain high interest rates between 6.5 and 14.25 percent in order to deter consumption.

It is now widely accepted that EU austerity policies prolonged lower growth, and thus lower tax revenue, causing debt to skyrocket. Growth in the United States diverged upward after policymakers embraced stimulus, and has remained robust in comparison with other major economies. But neither Washington nor Brussels chose to raise borrowing costs after the 2008 crash. In contrast, Brazil has hobbled itself with both austerity and high interest rates.

The saddest part of Brazil’s latest “lost decade” is that the value of its major exports has since recovered to pre-2014 highs amid another commodities boom. In 2023 and 2024, Brazil’s trade surplus rose to record highs of more than $87 billion, but GDP growth of 3 percent has been only a fraction of that seen during the first commodities boom. Were it not for the damage inflicted by central bankers, growth would be far greater, and the country less in debt. Even many market-oriented commentators acknowledge the validity of Lula’s critiques, but defend economic self-sabotage on the grounds that the president cannot criticize central bankers.

The solution then should be simple: The BCB must cut interest rates in the near term, incentivizing both consumption and investment. The South American giant must also reduce its dependence on volatile commodities and restore its midcentury industrial prowess. The most logical way to do so is to expand existing agricultural, mining, and hydrocarbons exports in the near term, while investing the proceeds in a long-term program of heavy industrialization.

Up until recently, the country was making some progress on all of these fronts. In 2020, the Bolsonaro administration abandoned austerity amid the economic fallout of the pandemic. Three years later, Lula significantly expanded oil and mining concessions, raised the minimum wage, and passed a historic tax reform, boosting state revenues. By the summer of 2023, the BCB began finally cutting rates amid a detente with Lula and preceding drop in inflation. Finally, in January 2024, Lula unveiled a $60 billion industrial plan, the incentives from which led to Stellantis, Toyota, Hyundai, and General Motors announcing $14 billion worth of investments in Brazil, with an additional $30 billion secured from Chinese firms in the year prior.

“Brazilian elites actively disdain the thought of reindustrialization.”

One by one, a chorus of market fundamentalists in the media and business world as well as the BCB undermined each of these gains. In 2023, oil production peaked at 4 million barrels per day, with a 60 percent increase in the state firm Petrobras’ shares. In any healthy economy, this would be deemed a success, but in Brazil, shareholders have been furious at Lula for prioritizing increased production over dividend payments. In the same vein, efforts to boost mineral and natural-gas production have also upset investors. Moreover, Brazilian elites actively disdain the thought of reindustrialization—never mind the fact that Brazil’s protectionist period birthed the country’s most important firms.

This year, investors have caused the stock market to stagnate by pulling cash to protest Lula’s supposedly dangerous spending and his critiques of the BCB. All of this paid off when markets finally brought the red menace to heel. In July, the administration made $5 billion worth of budget cuts, to the applause of investors; and in September, Gabriel Galipolo, Lula’s nominee for BCB president and a longtime ally of the president, surprised markets by suggesting he was in favor of rate hikes.

The Brazilian experience holds a number of lessons for observers stateside. Like Brazil, the United States is highly in debt and runs large budget deficits. In both countries, high interest rates have dampened job growth, industrial policy, and anti-inflation efforts alike, while causing housing prices to jump by making it more costly to build new homes.

The United States has its own vociferous critic of central bankers: Donald Trump. Indeed, this is a lesser known point of agreement between the GOP presidential nominee and progressive populists, including not just Lula, but such ostensible nemeses as Elizabeth Warren. Both in and out of office, Trump has floated firing Powell over the body’s insistence on raising rates. And while he has since walked back firing his own appointee, the mere insinuation he would not respect Fed independence has caused panic. Had he been re-elected in 2020, it’s possible that a Trump-Fed brawl could have mirrored that between Lula and the BCB.

To be sure, the question of central-bank independence isn’t to be taken lightly. The legislature and judiciary shouldn’t be beholden to presidential diktats, and the same logic applies to a nation’s lender of last resort. But it doesn’t follow that the actions of bureaucrats at the Fed or BCB should be treated as sacrosanct. Incoherent and opportunistic as Trump may often be, one of his recent statements on the subject was eminently reasonable: “I have the right to say I think [rates] should go up or down. … I don’t think I should be allowed to order it.”

In the same vein, Lula acknowledges the importance of monetary independence but argues in favor of the interests of the many over the few, stating that in his terms in office, he “never interfered with the central bank’s autonomy,” but asking: “That autonomy serves whom? The more people pay in interest, the less money they have to invest.” The dire consequences of economic groupthink in Brazil are evident for all to see. But with any luck, a new consensus stateside may offer a viable alternative for other nations to follow.