When people hear about government intelligence work, they typically imagine clandestine meetings in dark alleys—perhaps enhanced by future-tech spy gear—or else analysts in a windowless building combing over the latest electronic intercepts and satellite imagery to unravel a nefarious foreign plot before the world ends. But the focus on how spies, spymasters, and top-secret puzzle-solvers do their work obscures a more fundamental truth: that the job of the intelligence agent is to provide policymakers with an advantage when they make strategic decisions.

Today, the US Intelligence Community’s policies, posture, and personnel are misaligned with what is needed to maintain national decision advantage over America’s chief rival: an ascendant China.

Beijing is a peer rival across military, economic, technological, and diplomatic domains. US intelligence agencies aren’t positioned to support strategic decisions across all those domains. Failure to prevail in this generational confrontation, either as the result of a decisive military loss or a slow erosion in US power, would have disastrous consequences for the freedom, economic opportunities, and safety of every American.

Many of these failings are structural, and not the result of mistakes attributable to a particular leader or policy decision. The bravery, talent, integrity, and patriotism of US intelligence officers are being applied against the wrong problems and in the wrong ways. It is worth examining, therefore, what it is that US intelligence agencies really deliver for the tax burden and legal free hand they need to do their work, when in our recent history they have succeeded and failed, and what lessons can be learned from all of this.

The intelligence officer’s task is to use any legal method (according to one’s country’s own laws) or information available to put geopolitical, technical, and economic developments into context and understand how events might unfold, how foreign leaders might react, and what opportunities exist to change undesirable circumstances. Often that advantage is supplied not by furtive spying efforts fit for movies, but in more mundane ways, such as reading foreign newspapers, consulting scientists on advanced but unclassified developments in their field, or receiving missives from well-placed diplomats.

“Intelligence officers exist to help their side stay one step ahead of the competition.”

Put more simply, intelligence officers exist to help their side stay one step ahead of the competition, be it another head of state or the leader of a terrorist cell. That could mean outmaneuvering an adversary on the battlefield, showing up to a diplomatic negotiation already understanding a counterpart’s bargaining position better than they do, developing countermeasures to a still-under-development secret weapon, or knowing the right non-obvious pressure points to end a threat.

But the way those secrets get combined with more open information collection and turned into useful intelligence to improve the thinking of friendly leaders is very much a product of each age. For US intelligence, this has often meant restructuring agencies and rejiggering budgets and legal authorities in the wake of disaster, when our adversaries have had an advantage in decision-making through either superior concealment of their secrets or failures by our own side to put the right information into the right context at the right time.

Despite the triumphal mood that followed World War II, the United States also remembered the failure to identify and act on intelligence about Japan’s designs to attack Pearl Harbor. The response was the National Security Act of 1947, which created the Central Intelligence Agency, consolidated military bureaucracy into the Department of Defense, and streamlined Cabinet-level advice on security issues to the president.

It was a national-security bureaucracy well-suited to its age. The chief US competitor was the Soviet Union, with its even larger and more centralized decision-making apparatus. Intelligence on Moscow’s long-term plans and intentions was collected from all over the world, then filtered and compared and analyzed, all with an eye toward enhancing each president’s ability to outmaneuver his Soviet counterpart under the shadow of nuclear arms that guaranteed mutually assured destruction for any serious miscalculation by either side. The emphasis in intelligence work was on producing accurate long-term estimates of military power, being positioned globally to avoid geopolitical surprises in the Third World that could tip the balance of power, and protecting one’s own secrets at any cost.

US intelligence work over the last two decades has, of course, been reshaped by the changes made following the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001. The 9/11 Commission, which investigated intelligence failures in the aftermath of the calamity, found intelligence agencies lacking in imagination, resistant to working with one another, and unduly hampered by legal restrictions. That careful, plodding, and literal approach might have made sense for great-power conflict or domestic law enforcement, but it left intelligence agencies unsuited to the new challenge of preempting relatively small but deadly potential terror incidents worldwide—the proverbial “poisonous snakes” that CIA director James Woolsey warned in 1993 had replaced the slain “dragon” of the dissolved Soviet Union.

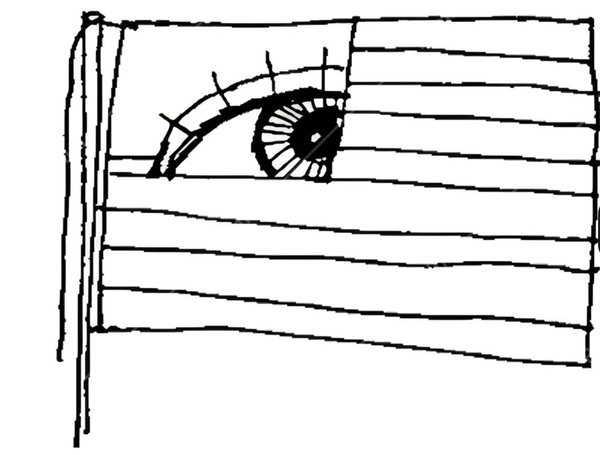

Intelligence work in the new era of digital communication was powered by a global electronic-surveillance panopticon that empowered special operators and law enforcers, as well as allied and friendly services worldwide, to directly disrupt terror cells in their neighborhood. This meant an emphasis on consensus and quick and often dirty tactical and targeting analysis.

Successful intelligence support during a prolonged confrontation with China won’t look like it did either during the Cold War or the War on Terror. In both of those cases, the United States enjoyed enormous resource advantages. America benefited in the first decades of the CIA’s existence from a larger and faster-growing economy, historic rates of civilian technical innovation, and a stronger network of formal allies than Moscow could muster. Responding to the terror threat from al-Qaeda and its affiliates and imitators, America had orders of magnitude greater resources across all domains than the largely non-state actors it confronted.

In an earlier era, preventing challenges to the status quo from emerging took precedence over helping US leaders get ahead of challenges, grow their resource base, or make the most efficient use of limited budgets. In the case of the twilight struggle against Soviet Communism, the priority was preventing nuclear war by avoiding miscalculation, disruptive changes to the balance of power, or unintended provocation. After 9/11, Washington sought to forestall even a single successful terror attack anywhere in the world—a daunting task, despite enormous US resources devoted to the task, given the global scope of the threat.

During the Cold War, single strategic decision points could be supported with equally strategic, centralized intelligence to attempt to maintain US military and diplomatic superiority against a single well-known foe. In the War on Terror, that same system turned toward single decisive moments—raising alert levels when an imminent terror strike was detected, or tracking the location of a key terrorist cell leader—against malefactors ranged across the planet.

To prevail against Beijing, intelligence agencies will need to unlearn some of those lessons.

The danger of miscalculation remains, but the Middle Kingdom’s rapid pace of technological innovation and economic development mean that Washington can’t win by merely containing its rival and running out the clock. If intelligence agencies simply seek to support a stable status quo, it may be America’s adversary that emerges on top this time. A new Cold War will be fought as much in one of hundreds of laboratories and global manufacturing bases as in any kinetic battlefield or dark-alley spy game. When the earlier Cold War intelligence paradigm was created, the US government itself funded more than two-thirds of American research and development; today, that figure stands at less than a quarter.

“Spy agencies must learn how they can support industrial policy.”

The Intelligence Community has spent decades improving its ability to inform geopolitical and military policy. Now, spy agencies must learn how they can support industrial policy. To stay abreast of the latest discoveries around the world, US intelligence agencies will need to take greater risks in expanding their intelligence sharing and customer set within the United States. This move would help technology developers in Silicon Valley and nascent industrial titans in Columbus, Ohio, outmaneuver their counterparts in Shenzhen and Guangzhou, without failing to answer the questions of each president in the Oval Office trying to outsmart his counterpart in Zhongnanhai.

America’s leaders already listen to what well-connected private-sector experts have to say is going on in the world and need to continue doing so. But they can’t be satisfied with the current practice of only occasionally sharing some classified intelligence with cleared counterparts in key industries, as important as that is for preventing cyberattacks and other threats to those firms.

Private-sector managers and workers must have a more direct seat at the table, able to task agencies, provide input on intelligence priorities, and offer meaningful feedback on the utility of agency work that affects budgets and personnel promotions going forward. Making the Department of Commerce a member of the US Intelligence Community would be a good start; so, too, would be the inclusion of a rotating group of cleared members of critical infrastructure sectors and industries in decisions affecting the National Intelligence Priorities Framework process, where the triaging of efforts against various problems occurs.

The People’s Republic has already profited from our government’s uneven ability to work with our own innovators, stealing hundreds of billions of dollars of US intellectual property in over a decade of cyber thefts before agreeing to curtail the behavior only once they had caught up and become innovators themselves. Our intelligence agencies took too long to recognize the national-security importance of what they had been treating as a series of criminal matters—of interest to the companies themselves, but of no import to the commander in chief. In the aggregate, though, this hacking spree helped China pose a serious challenge to US technical supremacy, while also imposing long-term costs on the American economy, probably costing thousands of American jobs every year, according to industry studies. But since each individual hack was well below the threshold for damage that would provoke a national crisis to which the president needed to respond, the intelligence and national-security apparatus never kicked into gear until the damage was done to many hundreds of companies and their workers.

That same pattern repeated again in recent years with the rise of ransomware. Contrary to many people’s expectations, most hackers request only relatively small ransoms from their targets: usually tens of thousands of dollars or less. Certainly nothing that would rise to the level of a White House Situation Room briefing. But because ransomware has gone unchecked, individual small threats staying below the Intelligence Community’s threshold for action have in more recent years disabled hospitals, threatened energy pipelines, and allowed Beijing to gain a foothold into critical American infrastructure for potential future military attack.

With the private firms on the front line of foreign attacks and at the forefront of making the decisions and discoveries that will determine the future of US-China competition, pushing intelligence to them that serves their needs and improves their competitiveness and rate of innovation, while explicitly responding to threats against them, has never been more important. Equally important, intelligence agencies will need to improve their ability to hire personnel with true business expertise from more diverse professional backgrounds, probably with added incentives for technical knowledge needed to understand market developments and supply-chain risks that analysts today aren’t going to pick up in their international-relations classes.

Across the West, right-wing populist movements are giving rise to a global outlook far different from the standpoint from which the overwhelming majority of intelligence analysts are trained to see the world. Will US intelligence agencies be able to treat the rise of populist parties in Europe as opportunities, rather than problems? Can they fairly examine alleged democratic backsliding not only in conservative Hungary, but in hyper-liberal Scotland? Can they fairly weigh the pros and cons of shifting the NATO alliance burden further to European allies, freeing up US resources for the Pacific, without resorting to moralizing about the “rules-based order”? When writing analysis that considers the repercussions of a particular move, can they weigh the impact on American jobs, freedom of speech, and domestic stability alongside any changes in the global chess game vis-à-vis adversaries?

Individual accountability in promotions and performance reviews for analytic accuracy and impact would go a long way toward properly incentivizing objective analysis. So, too, would competition for resources and influence from opening a greater number of positions to real-world experts in the private sector and academia with relevant subject-matter expertise. The State Department’s relatively small Bureau of Intelligence and Research, known as INR, has long garnered acclaim from policymakers for providing the best pound-for-pound intelligence analysis in the community, based in part on the small number of analyst-experts who own each piece and take responsibility with their own policymakers for accuracy. Probably part of the solution is to make the rest of the community’s coordination and professional practices look more like INR’s.

Concerns that the CIA was willing to spend nearly limitless sums on marginal improvements in intelligence capability date to at least the early years of the Nixon administration, as captured in the Schlesinger Report, but are even more salient today. The report’s key findings—that “intelligence functions [have] become increasingly fragmented and disorganized”; that collection of intelligence has “become unproductively duplicative”; that continued growth of the agencies is “largely unplanned and unguided” and “exceedingly expensive”—are as applicable now as they were in 1971, despite post-9/11 reforms that aimed to address these crises. The solution involves rolling back some of the duplicative sprawl to free up resources for better performing competitive intelligence functions, while demonstrating responsibility to the citizens paying for it.

The report went on to note that “despite the richness of the data made available by modern methods of collection, and the rising costs of their acquisition, it is not at all clear that our hypotheses about foreign intentions, capabilities, and activities have improved commensurately in scope and quality.” This comment was directed mainly at the shortcomings of intelligence analysis in the Vietnam War, but it could just as easily describe how America’s more than $100 billion intelligence budget failed to lead to the right conclusions on—to name a few—Covid origins, the Oct. 7 attack on southern Israel, the takeover of Afghanistan by the Taliban, the threat posed by Huawei to telecommunications infrastructure, or the rapid spread of the Arab Spring in 2010.

“Increased spending on ever more advanced technical solutions hasn’t led to better outcomes.”

Massively increased spending on ever more advanced technical solutions hasn’t led to better outcomes, but it has stuck the American taxpayer with a swelling bill. The development of better metrics for intelligence outcomes and mapping budgets accordingly—rather than continuing to buy advanced capabilities with a loose connection to the questions decision-makers are actually asking—has been needed for nearly five decades, but it is absolutely vital if we are to outcompete a Chinese spying apparatus with several times as many personnel, fewer legal restrictions, and just as large of an economic and technical base to leverage. The next president should commission his own Schlesinger Report to begin grappling with these structural issues and developing a serious strategy for how intelligence agencies can stay relevant in competition with China.