On Tuesday, March 8, Hawaii became the last state to announce the end of its universal indoor mask mandate—the last domino to fall after the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention revised its masking guidelines in late February. Many are reluctant to let go, but the trend seems to be toward relaxation of pandemic measures, and at least for now, Democratic governors seem eager to avoid new restrictions ahead of November’s midterm elections.

It would be a mistake, however, to assume that masks, lockdowns, vaccine mandates, and other restrictions are gone for good. There has been no fundamental reconsideration of the premises that guided the pandemic response, despite the demonstrable failure of these policies to forestall the spread of the virus during the Omicron wave (and beyond). Rather, Democratic leaders and the liberal public seem merely to have replaced one crisis with another.

On the national and international level, most messaging has pointed toward easing restrictions. As Politico reported, the consensus at a February meeting of public-health authorities in Munich was that the “emergency phase of the pandemic” should be left behind. At the same time, the Russian invasion of Ukraine has pushed the virus below the fold on every major news site and swallowed up primetime broadcasting, reinforcing the impression that we have moved on.

Yet a feeling of déjà vu should accompany the tentative sense that we have left the pandemic behind. We have been here before, more than once. Just under a year ago, the CDC relaxed masking recommendations after the initial uptake of vaccination, and many states and municipalities followed the agency’s lead—until the Delta variant triggered a panicked reversal in the agency and in liberal areas of the country. It was at this point that the realities of blue and red America diverged. In GOP-governed states, the pandemic looked essentially over in policy terms by a year ago, whereas Democratic states veered between restriction and reopening as Delta and Omicron brought new case surges.

“Pandemic mitigation measures now serve primarily as propaganda for themselves.”

Most liberals, it seems, have been conditioned to overlook these oscillations, to treat the given policy of the moment as the natural and logical response dictated by “science” and to forget that they and their leaders held the contrary position not a week earlier.

The most blatant example of such learned amnesia came amid the summer 2020’s Black Lives Matter protests. The same people who had intoned “stay home, save lives” over the previous few months suddenly exhorted the public to crowd the streets; leading epidemiologists offered a full-throated endorsement to this pivot, on the grounds that “white supremacy is a lethal public health issue that predates and contributes to Covid-19.”

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has occasioned a similar pivot. Prominent all-Covid-all-the-time Twitter pundits lately turned to condemning Vladimir Putin and intoning about the Russian nuclear threat, perhaps in response to their follower base’s shift in attention. The Ukraine invasion, much like BLM two years ago, has furnished a portion of the public, as well as Democratic politicians and the “expert” class, with a moral pretext for looking away from the pandemic.

These crises are primarily experienced through media spectacle and emotional contagion on social media, and they are interchangeable. Dissimilar events may play a similar role in the collective moral and emotional economy as long as they fit into a Manichean schema pitting villains—Putin, Donald Trump, racist cops, anti-vaxxers—against victims on whose behalf outrage may be performed.

Which is why it shouldn’t surprise anyone when new restrictions follow another round of Covid hysteria. New York Times columnist David Leonhardt may now be prepared to admit the failure of pandemic measures, yet the concession isn’t based on a deeper rethink: “If a new variant emerges, and hospitals are again at risk of being overwhelmed, then reinstating Covid restrictions may make sense again, despite their modest effects.”

The policies that remain in place likewise expose an unwillingness to question the rationale behind the largely useless measures implemented in the past two years. For instance, when mask mandates were retired in New York City, there was one exception: children were still required to mask at daycare and kindergarten due to their ineligibility for vaccination. This is despite the fact that unvaccinated children are still at lower risk than many vaccinated adults, and that even the World Health Organization recommends against masking for this age group. Meanwhile, the city’s retention of vaccine mandates for employees initially allowed unvaccinated fans to crowd sporting arenas while unvaccinated players were still barred from playing. Now, an exception has been made for players—but concession-stand workers in the same arenas are still required to get the shot to keep their jobs.

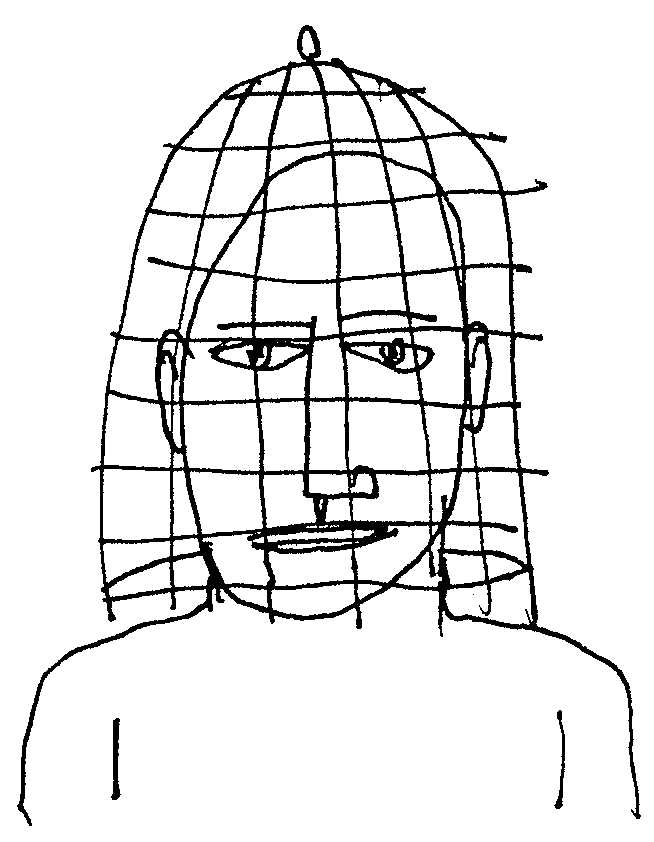

These and similar policies are blatantly irrational from the standpoint of public health but serve a political purpose. Keeping a confusing patchwork of policies in place communicates the continued necessity of such measures, even in periods of minimal transmission, and thereby preserves the rationale for more extensive reimplementation at some point in the future. In other words, pandemic mitigation measures now serve primarily as propaganda for themselves.

A Republican landslide in the midterm elections this fall looks plausible. While this outcome might make politicians averse to reimplementing draconian public-health measures in the near future, there is good reason to be skeptical that it will lead to any significant accountability for the failed and harmful policies of the past two years. For a grim precedent, we may look to George W. Bush’s War on Terror, which shared many salient features with the war on Covid. Bush was roundly repudiated at the ballot box in 2006 and 2008, but despite the passions of the voting public, the War on Terror’s architects were never held to account by the Obama administration, which on the contrary retained much of Bush’s policy agenda and security apparatus.

This was partly because another case of amnesia took hold when a crisis erupted in 2008: the global financial crash (for which, likewise, none of the relevant actors were ever held accountable). In a mediatic and political universe that feeds off of indefinite states of emergency, one crisis may simply succeed another, generating a new array of ad hoc policies and dubious regimes of bureaucratic oversight. By the time the failures of this regime have become apparent, a new catastrophe reorients our moral passions, and the pattern repeats itself with minor variations. Covid-19 now hovers just out of sight, with explainers on the new BA.2 variant languishing below the latest Ukraine updates. But it remains a “reserve crisis” ready to be summoned up again when others have receded. As we now know too well, a virus has no endpoint, only new variants. In a world where reality is made and unmade by viral media, a similar interminability has taken hold.