The New York State Senate is quietly considering a bill to allow euthanasia, which may be brought to a vote as early as this week. The bill would allow patients with a terminal illness or condition to request lethal medication if their doctors expect they have less than six months to live. (It is euphemistically called “medical aid in dying,” and the bill specifies that it is not to be considered euthanasia or suicide, but I will refer to it in those terms because that’s what it is.)

It is tempting to think of euthanasia as a legitimate option when we imagine situations of terrible pain in which it would seem like the merciful option. It can be perfectly reasonable to put down a suffering dog, for example—so why not also a man? Or one might see euthanasia as a legitimate recognition of human dignity and autonomy. Films such as Million Dollar Baby and Mar Adentro depict thoughtful, morally serious people who want euthanasia whether or not society condones it.

But there are problems with this way of thinking.

We can start with the problem of pain, to which euthanasia is simply not a necessary solution. We already have palliative care and hospice, arrangements that make it possible for patients to take dangerously high levels of pain medications. Normally patients aren’t allowed to take such extreme doses, but in end-of-life contexts, the medical establishment rightly recognizes that it’s a worthwhile tradeoff to accept the risks associated with the higher doses. There is simply no reason to offer euthanasia when powerful palliative medications like morphine exist.

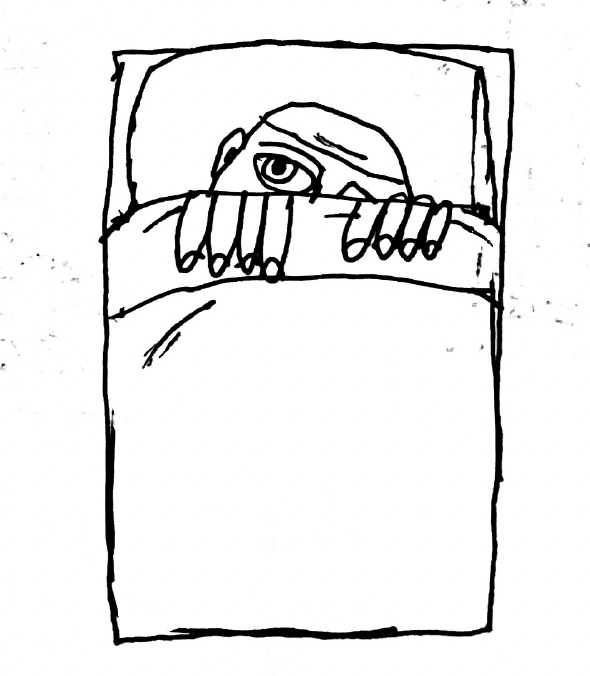

But what about the people who would choose euthanasia over even a painless death, because they feel it is “cleaner”—that going out on their own terms would allow them to stay in control? They may be afraid of going to pieces in the ways people often do at the end of their lives: They’re unwilling to lose their mind, to lose control of their limbs, to lose control of their bowels. And they may also be hesitant to have their family endure the emotional pain, the work, the time, and the financial burden which can be involved in caring for a dying person over an uncertain and sometimes extended period of time.

But there’s a big problem with this way of thinking about dignity and autonomy. There are lots of experiences that people will find uncomfortable and which we may want to avoid: uncomfortable because we don’t want to undergo something difficult, uncomfortable because it doesn’t accord with our idea of the kind of person we are, uncomfortable because it exposes us to embarrassment, or because it makes it feel as though we are imposing on other people. And in most cases, we don't say that the fact that someone is uncomfortable is a legitimate reason for them to kill themselves.

We don’t, for example, nod sagely when an undergraduate at an elite university kills himself after failing to pass a challenging class. We don’t say things like “he went out on his own terms,” or “at least he knew what he wanted” or “he didn’t want to put his family through the pain of what lay ahead of him,” although technically this is all true in a limited sense. No, we pity him for the mental health problems that led to his death, and we recognize that his view of life—the view according to which the only life worth living is one that involves certain very specific achievements—is a stunted way to think about things. There are lots of ways to live a good life, including ways that don't involve being more successful than 99 percent of people.

In other words, very few of us think that suicide is normally a legitimate choice, that you need to support my right to kill myself for any reason whatsoever: because I'm depressed, or because I wish I were smarter, or because I drank too much and got really upset. Instead, when it comes to suicide, most people think that if it should be allowed at all, it should only be allowed for “good reasons.” For situations in which any reasonable person might want the option of killing herself.

For example, we are tempted to imagine that the person who faces the prospect of drooling on himself and losing his mind is in a different category from the college kid with an excessively narrow idea of what it means to lead a good life. Unlike the college kid, the terminally ill patient is not afraid of dropping from the 99th to the 98th percentile for success, health, or other widely agreed upon markers of the good life. Instead, he is facing a far steeper decline, to the 5th, 2nd, or even 1st percentile. So it is tempting to imagine that it is reasonable for him to choose death over such a dramatic decline.

But the trouble with this approach is that it involves us making a distinction between lives which we all agree are definitely worth living and lives which may or may not be. This is one of the reasons that disability-rights activists often oppose euthanasia. When we legalize euthanasia and establish criteria for eligibility, we tell everyone who meets those criteria that their lives are—unlike everyone else’s—of questionable value. Essentially we say to them: “Have you thought about killing yourself? I mean, I can see why you would.”

When euthanasia is permitted, all sorts of institutions—nursing homes, hospitals, sometimes even families—will pressure patients in subtle and explicit ways to end their lives. Expensive patients. Inconvenient patients. Vulnerable patients. The availability of euthanasia lets institutions wash their hands of their duties to the impoverished and uncared for.

Hospitals already have incentives to get rid of “inconvenient” patients. Sometimes this leads to active criminal activity. A particularly egregious case occurred in Florida, in which a local hospital network conspired to have elderly patients in nursing homes given a state-appointed guardian without their consent, and without informing their families. Independently, the hospital system paid the guardian in question millions of dollars. She would then assign the patients DNRs against their will, and many of the charges unwillingly died preventable deaths as a result.

When euthanasia is an available option, it becomes possible for hospitals to “eliminate” inconvenient and expensive patients—without going to such lengths. There are all sorts of ways to make your patients really unhappy, so many ways to make euthanasia look attractive. Do we really want to put euthanasia on the table for hospitals and insurance companies, for nursing homes and doctors? To give them even strong incentives to make their patients miserable?

When it comes to the New York bill in particular, it’s particularly concerning that the law does not prevent health-insurance companies from reducing what they are willing to cover based on the availability of euthanasia. It only forbids insurance companies from doing two things: They may not actively advertise suicide as an option, particularly in the context of denying coverage, and they may not change what they offer on the basis of a given individual’s choice to request, or not request, euthanasia.

“Patients will almost certainly die under this bill who would have otherwise survived.”

It is also quite concerning that the bill instructs that the cause of death for euthanized people be marked as whatever terminal condition they suffered instead of the real cause of death (lethal medication). In other words, there will be no easy way to track how many deaths are caused by euthanasia, which makes it unnecessarily difficult to track the euthanasia rate for a given nursing home, hospital, or doctor. The bill also stipulates that euthanasia must be treated by life insurance companies as a natural death. This could, obviously, lead to situations in which a given patient was keen to die on a particular timeline for financial reasons.

There are many problems with the New York bill. It may interfere with our access to good health care. It creates perverse incentives. It expresses a horrifying view about the lives of those who are sick and dying. There is also the problem that doctors are not, in fact, omniscient; patients will almost certainly die under this bill who would have otherwise survived their allegedly terminal conditions. But above all, it is evil to kill an innocent person. And when we get in the business of doing this sort of thing, who knows where it will end?