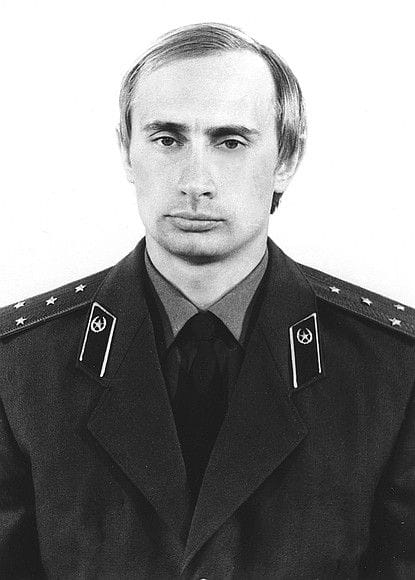

War is complicated. This should go without saying. But from the outset of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the elite media have offered us a different, yet oddly familiar, tale: a simple story pitting insiders against outsiders, reason against irrationality, good against evil. Vladimir Putin is the chief villain in this tale—first, possibly irrational; then, very nearly mad; and finally, definitely evil.

While relations between Russia and the West have been rocky over the past two decades, it wasn’t long ago that Putin was viewed as someone who could be reasoned with. In the aftermath of the 9/11 attacks, the Russian leader offered intelligence and material support against the Taliban in Afghanistan, assistance the United States happily accepted.

In 2017, French President Emmanuel Macron met with Putin to discuss, if tersely, the conflict in Syria and growing tensions in eastern Ukraine, as well as the persecution of LGBT communities in Russia. “We have disagreements, but we shared them, at least,” Macron said at the time. The French president even hosted Putin at Fort Bregançon in the Mediterranean in 2019, where the Russian leader complimented the Macrons on their tans.

As relations soured, however, a new narrative emerged. Putin is irrational and becoming “increasingly unhinged,” according to former US Ambassador to Moscow Michael McFaul. After Macron met with Putin in mid-February, the French president commented that the Russian leader had changed since 2019, becoming more “rigid” and “isolated.” Another French official called Putin “paranoid.” A member of the European Parliament commented following the invasion that Putin was “losing his sense of reality,” affirming suggestions that the Russian president had “gone mad.”

As events progressed, wild speculation about the state of Putin’s “mental health” roiled Western tabloids. A search for “Vladimir Putin” and “madman” in the Nexis news archive for the first three weeks following the invasion yielded nearly 800 results. Sources speculated on the medical etiology of his apparent sudden descent into insanity. He was suffering from long Covid or Parkinson’s; perhaps he was taking steroids.

Gradually this picture shifted from one of madness to outright evil. Commentators and political leaders began using terms like “genocide” to describe his actions in Ukraine. UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson stated plainly that Putin’s actions represented the clearest distinction “in international affairs between right and wrong.” Urging that Western leaders call Putin’s bluff and impose a no-fly zone, another observer argued that “restraint when confronted by aggressive evil is folly and self-delusion.”

It is clear that the rhetoric has escalated, but none of this is new. As tenuous allies become enemies, individuals can personify conflict and embody all that is bad in the world. This was the same path traversed by Saddam Hussein, who was gradually framed as a distant “other,” an irrational, madman, a “beast,” and, finally, “the personification of evil.” Irrational people in positions of power can’t be reasoned with. They are a danger and must be eliminated.

While there have been faint rumblings characterizing the conflict as a defense of freedom and democracy, the positive values for which war might be waged by NATO and is being waged by Ukraine have been weakly defined. If we cannot be sure what we are for, the existence of an unambiguous enemy at least shows us what we are against. It invites us to take a righteous stand against tyranny and wickedness. Putin offers an internally divided West an opportunity to construct its side as the reluctant hero forced to confront the irrational, if cunning, villain. Many of the stories we tell about conflicts take on this narrative. It’s simple, and it’s satisfying, but it comes at a cost.

As the linguist George Lakoff argued in relation to the Gulf War, what all of this does is create a “fairy tale of the just war.” This tale has a familiar set of characters and roles: a villain who commits a grave crime, and an innocent victim who suffers greatly. A hero emerges (who may also be the victim) to defeat the villain, often at great cost and sacrifice. The hero is honorable, is greeted as a liberator and with great gratitude and fanfare by the victim and community of the good and the just.

“We can become too easily convinced that dangerous wars are just and necessary.”

While conflicts indeed involve great acts of sacrifice and heroism, and certainly a great deal of evil, such stories simplify a complex reality and militate against caution. We can become too easily convinced that dangerous wars are just and necessary and even large death tolls are a worthwhile sacrifice.

Moreover, the ruler often stands in for the state itself. Thus, the press speaks of “Putin’s invasion of Ukraine,” and “Putin’s atrocities.” Russian soldiers and even Russians themselves both at home and abroad become personifications of their ruler. The enemy in its entirety is dehumanized and demonized. We can already see this happening with the cancellations of Russian performers and other representations of Russian culture in the West.

This is happening on both sides of the conflict. Putin defended the invasion as an attempt to “de-Nazify” Ukraine and protect ethnic Russians from “genocide,” drawing parallels with World War II. Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy’s address to British lawmakers on March 8 also drew heavily on World War II rhetoric, while Western caricatures explicitly liken Putin to Adolf Hitler. And you don’t negotiate with Nazis. The consequences are dire. Anyone alive during the Cold War or with any knowledge of the nuclear stakes should be wary of ratcheting up conflicts.

We are not in a children’s book or a Marvel movie, despite the insistence of some of our most serious-minded foreign-policy pundits. We can condemn the actions of a government and its leaders, but we must also understand the processes that lead to such heinous acts if we are to avoid them ever recurring.