The Vulnerables

by Sigrid Nunez

Riverhead, 256 pages, $28

Early on in The Vulnerables, the just-published novel by Sigrid Nunez set during the Covid lockdowns, the narrator comments that the government measures, confining people to their homes and punishing them if they break the rules, are “for the good of all: understood.” Nunez has a penchant for close first-person narration by characters who share her biographical traits—her work has often been categorized as autofiction—so this stands in for the authorial viewpoint of the book. Its milieu and worldview are that of the people who found lockdowns to be obvious. Many of us thought no such thing, however, which suggests that the book will have significant blind spots.

Nunez isn’t a household name, but her work is prestigious in the most rarefied literary spheres. The Vulnerables is her ninth novel; her seventh, The Friend, won the National Book Award in 2018. Her memoir, Sempre Susan: A Memoir of Susan Sontag, recounts her relationship with Sontag while dating the legendary critic’s son, David Rieff, in the 1970s, when Nunez was one of three assistants to editor Robert Silvers at the _New York Review of Books. _It is quite the pedigree and is matched by her achievements and her behind-the-scenes influence. Nunez was an autofiction pioneer, and she writes in a lyrical style defined by forming loose but provocative connections between subjects. These occur both on the overall narrative level and line by line. It is a deceptively difficult technique. Many writers attempt it, and few succeed as well as Nunez does.

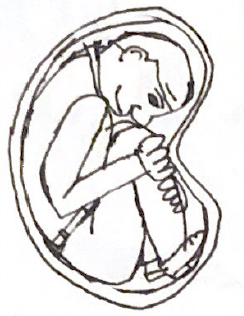

The Vulnerables is a lacework of anecdote, recollection, and observation that uses Covid to explore vulnerability in all its guises, mostly human, but not entirely, since a parrot is a significant supporting character. A single passage might contain an anecdote about an editor’s opinion of Madonna, a joke about misused language, and two lines about flowers. They don’t seem linked, but if you squint, they become a light-handed meditation on the ways we define ourselves. The book’s narrator is a writer, like Nunez, who appears to be about Nunez’s age (in her 70s) and lives, as Nunez does, in New York. In the lingo of Covid, she is “a vulnerable,” and this becomes a metaphor for the many ways that is true—physically as an aging person, emotionally as a solitary person, and socially as she navigates her friend group and relationships. The wider atmosphere of the pandemic suggests our vulnerability as a civilization, which Nunez enhances with a drumbeat of foreboding on climate change. Writing and its role also play major parts in the book, and can be seen as another form of vulnerability.

“We can’t avoid each other even when we try; relationships are inextricable from being human.”

All of this is delicately done but cumulatively feels frustrating. Nunez is often the woman of the moment, but perhaps not this one. Her solitary narrator is sent, ironically, into closer contact with others thanks to the isolation. She ends up first caring for a parrot whose rich owners have been caught out of town, and then falling into an unlikely friendship with a gorgeous young man who is also sheltering in place at the rich people’s house. There are lessons here—we can’t avoid each other even when we try; relationships are inextricable from being human. And Nunez plays it, to some extent, for laughs. Surely she is joking when she tells us that the parrot has been ethically sourced (from a breeder, not caught in the wild, of course) and has its own room, “lush with ferns and other plants,” whose walls have been painted to “look like a part of the South American rainforest that Eureka’s breed inhabited in the wild.” We are supposed to laugh—at least, I think we are—at the foibles of its rich owners, and at the parallels between the parrot’s gilded cage and their own. Nunez’s narrator (and the writer herself) grew up poor, and she likes to poke fun at the absurdist circles she is now exposed to.

And yet, it is hard to laugh when the pretty, pointillist anecdotes seem to obscure, rather than reveal, the tragedy. Covid can be a metaphor, but there is something tasteless about frolicking in a rich person’s home and not following the rules of social distancing (the narrator goes for long walks and is scolded by a friend for it; the young man comes and goes), while so many people are dying. And Nunez has always written very beautifully about animals, but the characters’ concern for the emotional stability of the parrot feels out of touch. The parrot has an entire support team; many people had no one. I looked for a layer of parody or self-criticism—perhaps the auto-fiction’s narrator is blind to her privilege, but Nunez, the real narrator, is cleverly condemning her?—but didn’t find it. Nunez ends the book with two surprisingly schmaltzy lines that seem to shut out that possibility: “ASKED: WHOM would you want to write your life story? / Someone with a gorgeous style and a great big loving and forgiving heart.”

In the early days of the pandemic, when the people who make up Nunez’s demographic and fan base were deciding lockdowns were obvious, I was frequently ill with rage over the people their logic left out. Schoolchildren. The depressed, addicted, and financially precarious. The people who would lose their small businesses at what cost to health, sanity, or life, we couldn’t know. And I was outraged that the blunt instrument of isolating everyone, regardless of need, prevented us from being able to spend time and resources on the vulnerable. When New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo sent contagious elderly people back to crowded nursing homes, I didn’t find it to be “understood.” Many people with opposing views—proponents of harder lockdowns and more masks; the virtuous few who did what we were supposed to—have felt a version of the same anger. We do need to forgive each other, but it isn’t easy, and books like this don’t help.

One of the many vulnerabilities that Nunez riffs on is that of the writer being a target of blame from readers. The Vulnerables’s narrator writes about receiving a letter from a man whom she says misunderstood something she wrote about sexual assault, saying “Where were YOU … when an OLDER WOMAN took advantage of ME?” She writes that the question pierces her, and she wants to write him back. Her friends say, “Don’t!” Nunez is at her best in moments such as these, when her signature style seems uniquely suited to capture the ambiguity and complexity of our reactions to each other. One wishes for more of these, and fewer blind spots of the type that claim that “half the nation” thrills to the idea of Donald Trump being illegally president for life, or that anti-vaxxers would rather kill Dr. Fauci than kill the virus. But even so, the book shines in the small scale, if not always in the large.