The radical feminist Andrea Dworkin described “the normal fuck by a normal man” as “an act of invasion and ownership.” In response, the underground artist and journalist Adam Parfrey made a startling claim. In “Cut It Off: A Case for Self-Castration,” he argued that if Dworkin was right, if merely having sex with a woman amounts to rape and slavery, then men have a duty to castrate themselves. Better to live as a eunuch than be condemned as a rapist.

MeToo has given new force to Dworkin’s argument. Since the movement emerged in 2017, the definition of what constitutes sexual assault and predatory behavior has broadened radically. It now includes flirtatious gestures once seen as harmless, as the case of Andrew Cuomo shows. And though men haven’t cut off their penises en masse, we have started altering our behavior. We think twice before complimenting a woman on her perfume, we worry about how long our gaze lingers, and we second-guess every interaction with the opposite sex.

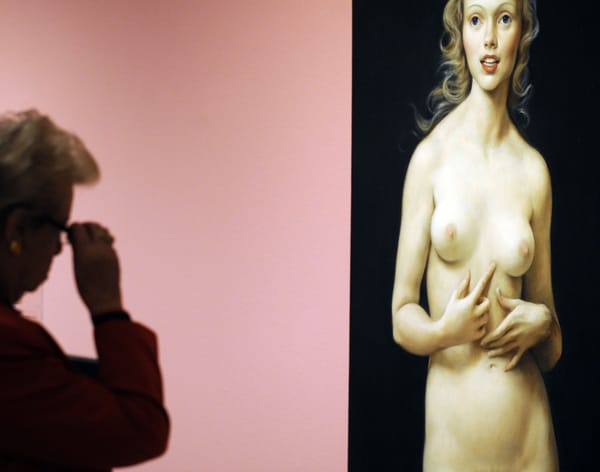

Though it began in the film industry, #MeToo soon upended the visual arts. This was bound to happen. The art industry is dominated by bourgeois and petit-bourgeois women who are often in steep competition with an ownership class still predominantly occupied by men. Institutional figureheads were the first to fall. Joshua Helmer, a manager at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, was accused of making women uncomfortable. Anthony d’Offay, an influential patron of the Tate, was accused of sexual harassment.

It didn’t take long for artists themselves to be targeted. Julia Fox accused the wheelchair-bound painter Chuck Close, who died last year, of telling the young star that her “pussy looks delicious” while she posed in the nude. An anonymous Instagram account called “Surviving the Artworld” published accusations against the post-internet artist Jon Rafman. One user described having consensual sex with Rafman multiple times but said she was put off by some of his aggressive behaviors during the encounters. She said that what had occurred “wasn’t rape,” but an “abuse of power.” None of Rafman’s accusers had at any point been an employee, student, intern, or subordinate of his. Three museums, including the Hirshhorn, suspended or postponed his exhibitions.