In the aftermath of Hamas’s shocking incursion into Israel, the Somali-American writer Najma Sharif asked rhetorically on X: “What did y’all think decolonization meant? Vibes? Papers? Essays? Losers.” As of this writing, the post has garnered more than 100,000 likes and nearly 25 million views. Sharif had one thing right: An impenetrable fog of vagueness has descended on this term. Before bloodshed consumed the Middle East once again, headlines pointed to how we might “decolonize” artificial intelligence, our diet, design, the theater, and “the city.”

In recent years, the concept of “decolonization” has been swallowed up by its metaphorical potentialities. The euphemistic second meaning the term has acquired in the process—a noncommittal verbal gesture toward symbolic restitution of certain historic wrongs—has facilitated its widespread endorsement by universities, NGOs, and media outlets. But as Hamas laid waste to southern Israel, writers, activists, and academics eagerly linked the term back to its original concrete referent: the often horrifically brutal struggles over territorial control that shaped the 20th century and that now risk returning to the fore as the Pax Americana falters.

The result is an uncomfortable predicament for elite institutions that have rhetorically embraced “decolonization”—but would surely prefer to eschew its more literal implications.

A clear indication of this impasse is the widely noted hesitation of major universities—usually so eager to issue solemn statements on the latest tragedy in the news—to comment publicly on the events of the past week. One example: New York University (my former employer) has thus far not issued a statement on its public social-media feeds on the events in Israel, even as it has made multiple posts in the same timespan commemorating Indigenous People’s Day. In the one email on the subject sent to the university community, newly inaugurated NYU President Linda Mills offered the following stilted reflection: “The violence that is raging now will likely intensify the feelings of those on our campus who hold strong views on the conflict.” NYU’s email also included—as such messages do—the number for the campus mental-health hotline.

“The demand for territorial restoration has become a metaphor for internal struggles over identity.”

Here we find an indirect clue as to the true nature of the “decolonization” project that has become a prominent part of higher education: Like much of what now takes place in elite institutions, it is ultimately a therapeutic enterprise. Battles over land and sovereignty are displaced onto the psyche; the demand for territorial restoration has become a metaphor for internal struggles over identity and belonging for which universities serve as a staging ground.

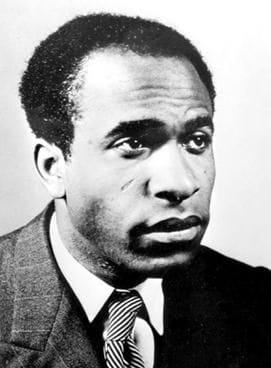

But intellectual history suggests this therapeutic function isn’t as easily detached from the concept’s violent implications as university administrators might like. The Afro-Caribbean philosopher Frantz Fanon, who is generally regarded as the originator of much contemporary thinking on decolonization, was also a practicing psychiatrist. In his 1961 manifesto, The Wretched of the Earth, Fanon argued that violence was essential to the defeat of colonialism for psychological as much as for practical reasons: Without a bloody struggle against the colonizer, the colonized can’t heal the psychic wounds imposed on them by colonialism. Out of this crucible, he prophesied in the early phase of decolonization, a “new man” would be born. For Fanon, decolonization was therapeutic only insofar as it was also real, material—and violent.

In recent days, pro-Palestinian protesters have tried to channel the cathartic effects of anti-colonial violence invoked by Fanon. But as Israel’s response unfolds with Western backing, a twin narrative has come to the surface on the other side, with some supporters of the Jewish state also seeking catharsis in the meting out of reciprocal devastation to Gaza. Relatedly, a difficulty with any one-sided application of Fanon’s account of decolonization in this context is that Israel has its own account of psychic regeneration through nation-building. Some early Zionists, too, sought to forge a “new man” through a violent struggle to overcome the psychic effects of millennia of anti-Semitism and stateless subjugation. Both narratives retain powerful appeal far beyond the territories in dispute.

There has been no more fraught subject than Israel in elite universities in recent decades. Most of them have influential constituencies on both sides of the conflict, and they have consequently acted in contradictory ways, often attracting the ire of both Israel’s supporters and its opponents. But their reluctance and awkwardness in responding to the current situation hints at a problem deeper than these divided loyalties. For years, elite colleges—and other influential institutions—have lent their prestige to once-radical concepts like decolonization, seeming to imagine that they could be kept separate from the gruesome histories out of which they emerged. Fanon, the intellectual godfather of “decolonial” thought, wasn’t so naïve. As the world becomes more dangerous again, the luxury of metaphorical radicalism may prove too costly to sustain.