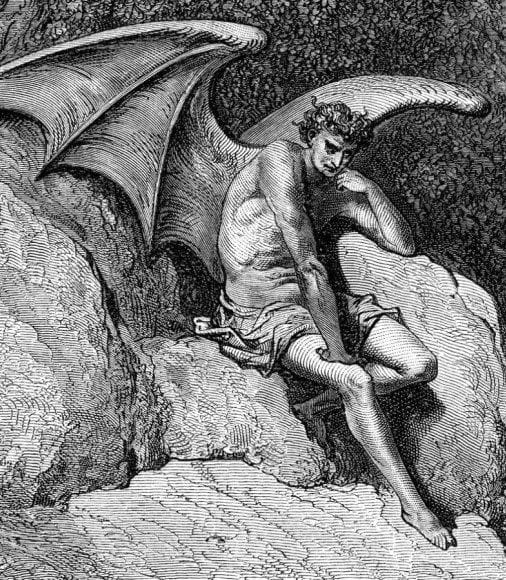

“I have always said the first Whig was the devil,” Samuel Johnson quipped, with sulphurous penetration. He was speaking of Milton, among other things. By 1778, when this acknowledgment was made, a man who had been a heretic even among Protestants had been long anointed England’s national poet. Within the English literary canon, the justification of God’s “monarchy” had been assigned to the care of a spiritual regicide. If rebellion, dissidence, and nonconformism reigned only in hell, where was the English cultural regime to be realistically situated?

“The Whig Interpretation of History” was not to be named as such until Herbert Butterfield did so, in 1931, but Johnson had already identified its theological undercurrent. Once a properly English historical process has established itself, dissent ascends predictably to power, interrupted only by increasingly fragile restorations. The ratchet mechanism is hard to miss. Roundheads become Whigs, then Liberals and Yankees, and then Progressives—and always, they win, at once domestically and internationally. In Ed West’s perfect coinage, “the right”—conceived relatively, which is to say dynamically—is always on the wrong side of history.

“Spiritual regicide installs itself ever more securely.”

In his introduction to God and Gold, Walter Russell Mead observes: