For someone working in the culture industries, the only thing worse than having the wrong position on a political controversy is having no position at all. Today’s artists are the high priests of the secular middle classes, with cathedrals (art galleries) in every major city. In recent years, rather than defend free expression and the exploration of beauty, the passé concerns of previous centuries, the art world has become the moral directorate of the social order. Malevich’s 1915 “Black Square” became 2020’s Instagram BLM square—and woe betide anyone who failed to correctly perform the ritual. As Guy Debord put it in his 1988 “Comments on the Society of the Spectacle,” “since art is dead, it has evidently become extremely easy to disguise police as artists.”

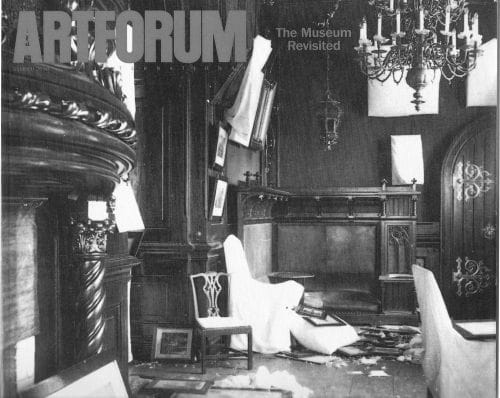

The growing tendency of artists to pronounce on everything from microaggressions to macropolitics shows that we need a fundamentally different understanding of the role played by artists and their institutions. The trend reached an apex last week, as a whole spate of open letters about Israel and Gaza were furiously signed and published. The frenzy culminated in the sacking on Thursday of David Velasco, editor in chief of Artforum, the prestigious contemporary-art monthly. Since then, several other Artforum editors—Chloe Wyma, Zack Hatfield, and Kate Sutton—have resigned. The hashtag #BoycottArtforum is circulating on social media, asking people to refuse to open or share links to Artforum content or to participate in any Artforum interviews or events. As the critic Adam Lehrer acerbically commented on X, “I haven’t opened an Artforum link in years, so I’ve been doing hella activism.”

What is going on? In a desperate bid to do something, anything, hundreds of artists and writers—including Nan Goldin, Judith Butler, Lawrence Abu Hamdan, Barbara Kruger, and Kara Walker—put their name to an Artforum open letter on Oct. 19 calling for art institutions and organizations to “make a public demand from our governments to call for a ceasefire.” While the signatories rejected “violence against all civilians, regardless of their identity,” the letter didn’t mention the horrific actions of Hamas on Oct. 7, namely, the kidnapping of some 200 Israeli civilians and the murder of at least 1,400 others, many killed in their homes and at a music festival. A later update on Oct. 23. made it clear that the letter writers also abhor the “horrific massacres of 1,400 people in Israel conducted by Hamas on Oct. 7,” but by then, the damage had been done.

Various critical responses appeared, including a letter by art dealers Dominique Lévy, Brett Gorvy, and Amalia Dayan condemning the original document for its “one-sided view.” Another letter, published in the online magazine Erev Rav, also criticized the statement, pointing out that undertaking a general condemnation of violence “without giving any room to the horrors of Oct. 7 undermines the moral stance taken by the letter’s signatories.” In the meantime, multiple signatories of the original letter, including Peter Doig, Katharina Grosse, and Tomás Saraceno, have retracted their support.

The Intercept has reported that Martin Eisenberg, an art collector and inheritor of the Bed Bath & Beyond fortune, “began contacting famous art-world figures on the list whose work he had championed to express his objections to the letter,” and that Velasco had been fired following a meeting with Jay Penske, the CEO of Artforum’s parent company.

Situating the firing in the context of repercussions facing those who speak out in support of Palestine, The Intercept quoted artist Hannah Black describing the situation as “absolutely McCarthyite” and describing “anti-Palestinians” as “willing to destroy careers, destroy the value of artworks, to maintain their unofficial ban on free speech about Palestine.” Speaking on background, one artist who signed the original letter told me that her work is being returned by a New York gallery that she has worked with for several years. Other artists are suffering similar consequences, she noted, with collectors putting pressure on gallerists, who are, in turn, blacklisting creators.

The fear of cancellation on the part of pro-Palestinian figures comes after many years of the same kind of behavior from those now calling for a cessation of hostilities. Over the past decade or so, cultural institutions and workers deemed insufficiently anti-racist have been attacked as fascist, white supremacist, and neo-Nazi. In 2017, the London art gallery LD50 was forced to shutter its doors after its owner, Lucia Diego, failed to be sufficiently critical of Donald Trump in a private message to an artist and dared to put on a workshop discussing “Neo-Reaction,” then a little-known internet idea. It was a key moment in the transition of artist to police officer. Since then, the #MeToo campaign has ousted a whole range of men from key cultural positions, including the previous publisher of Artforum, Knight Landesman. Accusations of “transphobia” against (mainly) women have seen many more de-platformed, ostracized, and deprived of income.

“Institutions and individuals don’t have to take a political stand.”

Are those artists who are now losing money and representation for failing to condemn Hamas able to understand that the free speech they desire is the same free speech desired by all the others they previously canceled? It would be easy—and somewhat gratifying—to point out their hypocrisy. But there is a real opportunity here to reject cynicism and careerism and, instead, to insist that while we may disagree, we don’t have to destroy each other. Institutions and individuals don’t have to take a political stand (but nor should they be punished for doing so).

None of us should be cowed by people simply because they shout loudly and appear to have a complaint. Institutions should reflect genuine diversity—that is to say, of viewpoint, above all—because the reality is that we don’t think alike, and for good reasons. To imagine that only some suffer and others don’t, is to be unwilling to acknowledge the harm we are all capable of perpetuating—even, or especially, those who believe themselves to be wholly on the side of the good.