The British satirical magazine Private Eye ran as its cover this week, on a plain white background, the headline “Man in Hat Sits on Chair.” The savvy, cynical reader is supposed to laugh at the truth so revealed—after all, the coronation of King Charles III, which takes place this Saturday, will indeed involve a man, in a hat, sitting on a chair, however fancy any of these things might be. This humorous reduction sums up a widely held view: All this pomp is very silly; we have surely evolved beyond the need for monarchs and ceremonies. This is indeed the perspective modern people are encouraged to adopt. We in Britain never exactly became republicans, but we certainly became good little nihilists, believing in nothing—but even then, not too hard.

But “Man in Hat Sits on Chair” also hints at an alternative interpretation, one in which the arbitrary and empty nature of the royal personage conceals a deeper genius. It is precisely in the contingent nature of the monarch, and of sovereignty itself, that something genuinely singular appears.

Anyone who has paid attention to his career knows that King Charles doesn’t fit the part of an empty figurehead. He is an erudite man who has spoken beautifully about nature, tradition, and the underlying unity of religion. His thinking on these matters is evidently influenced by the works of René Guénon, the French mystic and convert from Catholicism to Islam who founded the Traditionalist (or Perennialist) school of philosophy. In Harmony: A New Way of Looking at Our World (2010), Charles argues against scientific rationality and for a practice of revelation, which he describes as “when a person practices great humility and achieves a mastery over the ego so that ‘the knower and the known’ effectively become one. And from this union flows an understanding of ‘the mind of God.’”

Some are certainly excited—and why not?—about the prospect of a Traditionalist, esoteric, conservationist, simultaneously pagan and Christian king. The “Black Spider Memos” of the mid-2000s revealed a self-described “dissident” prince who wrote to ministers, in one instance, in defense of farmers, claiming in a letter to then-Prime Minister Tony Blair that he agreed with a Cumbrian farmer who told him that “if we, as a group, were black or gay, we would not be victimized or picked upon.” The King is also famous for talking to his plants, for loving classical architecture and hating the brutalist eyesores that dot London, and for eventually marrying his long-time companion Camilla. He is an individual, and a sensitive one at that.

Nevertheless, King Charles is duty-bound to remain politically neutral, and alongside his idiosyncrasies, he is aware of the paradoxically subservient nature of his role. The coronation ceremony itself is entitled “Called to Serve,” and the liturgy is focused on the theme of loving service to others. This understanding of the role of the monarch not as self-aggrandizing egotistical leader, but as ceremonial figurehead who bears the weight of history and his ancestors and the symbolic mantle of kingship, demonstrates how Charles conceives of his covenantal duty to the people.

“The ultimate source of royal power is its unnecessary quality.”

Under liberal capitalism, the world has a past, but this past is best forgotten. Instead, we are served up a perpetual present—not a meditative, contemplative, grateful present, but an anxious, acquisitive, elsewhere-directed and distracted present. Everything tends toward sameness amid the illusory variety: the same ideas, the same mass-produced objects. The persistence of British royalty—its empty power, its organic development in patchwork with law and Parliament and culture—reminds us that not everything must tend toward the same.

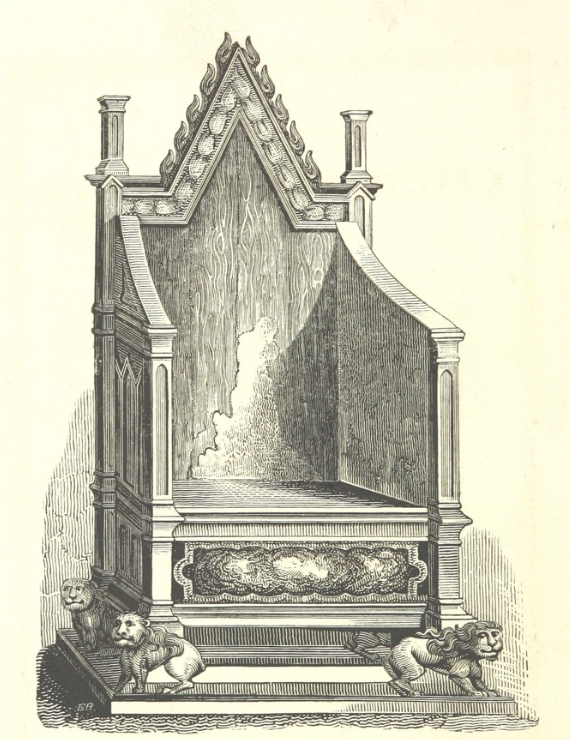

The ultimate source of royal power is its unnecessary quality, its sheer uselessness. As the 20th-century French philosopher Georges Bataille remarked: “Life beyond utility is the domain of sovereignty.” The role of sovereignty is to stand outside the mundane utilitarian logic of everyday life—and thus to allow us, for a moment, to throw off our quotidian concerns, precisely so we can carry on with them. We would not know what to do with the 12th-century coronation spoon that will be used to anoint King Charles III with oil consecrated at the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem, but we will fill our bank-holiday weekend with family, church, pets, hobbies, resting, or whatever we see fit. As Bataille goes on to say: “The truth is that we have no real happiness except by spending to no purpose.” Long live King Charles III, the Dutiful Sovereign of the Great Nothing!