In a controversial 1986 essay, “Third-World Literature in the Era of Multinational Capitalism,” the late literary critic Frederic Jameson argued that while the literature of the industrialized West had largely retreated from its political vocation, that wasn’t true of the great writers of the developing world. “Third-world texts,” Jameson wrote, “even those which are seemingly private and invested with a properly libidinal dynamic, necessarily project a political dimension in the form of national allegory: the story of the private individual’s destiny is always an allegory of the embattled situation of the public third-world culture and society.”

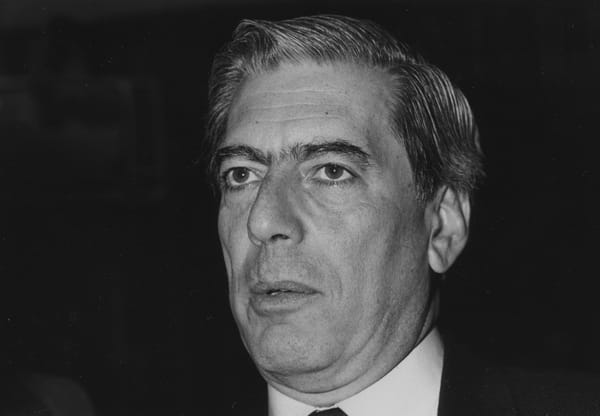

Whatever the broader validity of Jameson’s much-disputed thesis, it sums up the work of the Peruvian Nobel laureate Mario Vargas Llosa, who died on Sunday. He was a fervent aesthete and philosophical individualist whose oeuvre includes several works of literary erotica, but he never viewed these inclinations as at odds with the fundamentally political vocation of the novelist.

Vargas Llosa was as cosmopolitan a writer as the 20th century produced—he lived much of his life between Paris, London, Madrid, and Barcelona, and by the time of his death held a hereditary title conferred by the king of Spain and a seat in the Academie Française—but the bulk of his work revolved around the political fate of his impoverished, perennially crisis-ridden native country of Peru. In the opening lines of Conversation in the Cathedral (1969), one of the kaleidoscopic modernist epics that made his reputation, Vargas Llosa’s protagonist asks himself the question that also lay behind much of the author’s work: “¿En qué momento se había jodido el Perú?” (“In what moment had Peru fucked itself up?”)

The use of the reflexive verb is notable. The fashionable answer to such a question during Vargas Llosa’s youth (as now) was that Peru, like the rest of Latin America, had been fucked by others: first plundered by the Spanish conquistadors, then exploited by European and North American capitalists. In his early career, Vargas Llosa was a left-wing radical, and he wrote Conversation in a period when he was being regularly fêted in Fidel Castro’s Havana. Yet it is clear from the moral complexity and tragic sensibility of this and other novels that he never found such answers satisfying. To be sure, he never shied away from any of the dark facts of his country’s history. For instance, The Green House (1966), the novel he wrote before Conversation, depicts the kidnapping of indigenous children by Christian missionaries and the brutally exploitative rubber trade in the Amazon. But he refused to portray Peru and Peruvians as mere victims of foreign exploitation, or as anything but the agents of their own destiny.

“His break with the Latin American left was probably foreordained.”

Given this deeply held sensibility, his break with the Latin American left was probably foreordained. Its precipitating event was what we would now call the “cancellation” of the Cuban poet Heberto Padilla, who in 1971 was accused by the official national writers’ union of “exalting individualism in opposition to … collective demands” and promptly jailed by Castro. This led Vargas Llosa to organize an open letter protesting Padilla’s treatment. In the aftermath, he fell out with many of his fellow writers and intellectuals, most notably with his former close friend (and eventual fellow Nobel laureate) Gabriel García Márquez.

If Vargas Llosa’s early rebellion against the stifling mores of the Peruvian haute bourgeoisie had prompted him to embrace Marxism and the Cuban Revolution, his later rejection of the groupthink of Latin American intelligentsia led him to a new set of lodestars: Popper, Hayek, and Thatcher. While the political essays that resulted from this conversion often amounted to a rehashing of “classical-liberal” nostrums, the same can’t be said of the novels that marked his neoliberal turn: The War at the End of the World (1981) and The Real Life of Alejandro Mayta (1984) number among his greatest achievements, and among the finest political fiction of the past century.

Both novels deal with failed revolutions: the first with the real historical events of the Canudos War in late 19th century Brazil, where a messianic sect of peasants revolted against the newly proclaimed republic; the second, a fictionalized version of an abortive communist revolution in 1950s Peru. Both stories expose the deep disjunction between elites and the masses in Latin America. In War at the End of the World, Brazil’s progressive reformers are shocked to find that many of the rural poor they hope to lift out of backwardness view their secular republic as a blasphemous abomination and prefer a restoration of monarchy; in Mayta, a hapless urban intellectual leads a doomed uprising of Andean peasants, in a tragicomic foreshadowing of the horrors of the Shining Path war that was tearing Peru apart as Vargas Llosa was writing the novel.

The author faced his own real-life version of the same disconnect when he ran for president of Peru in 1990. His highbrow neoliberal reformist platform, derived from his first-hand observations of Thatcher’s England and readings of Hayek and Friedman, failed to win out over the wily populist appeals of the outsider candidate Alberto Fujimori. Ironically, after his victory Fujimori went on to implement much of his rival’s proposed economic program of shock therapy and privatization, while also installing himself as dictator and engaging in staggering levels of corruption and violence. Nonetheless, decades later Fujimori retains enough of a mass following to this day that his daughter Keiko will be a leading contender in Peru’s next presidential election.

Vargas Llosa was fascinated by the lure of transgression and the delirious excesses of human desire and imagination; Sade and Bataille were among his favorite philosophers. He defined the task of the great novelist, in his academic study of his frenemy García Márquez, as “deicide,” in that the writer’s demiurgic conjuring up of a total reality amounted to an unseating of God. In this way, the novelist was the twin of the revolutionary, as well as of the dictator who sought to impose total control on a nation (hence García Márquez’s sense of kinship with Castro). For Vargas Llosa, however, literature offered a space for the sort of radical experimentation that would bring catastrophe if transformed into a political program—a way to pursue, as he called in his book on Victor Hugo, “the temptation of the impossible,” but with less collateral damage.

In his final years, though, Vargas Llosa expressed increasing enthusiasm for the charismatic populist mode of politics he had long presented as mortally dangerous. He supported Jair Bolsonaro over Lula in Brazil, even though he had qualms about the former’s vulgarity and had praised the latter’s market reforms in the 2000s; he also endorsed Argentina’s Javier Milei, and in 2021, he even backed Keiko Fujimori, the daughter of his detested nemesis.

This evolution was also perhaps inevitable. For most of Vargas Llosa’s career, the sort of elitist politics he espoused was the only game in town when it came to neoliberal economics. The Latin American masses may have been wary of left-wing utopias, but they have often also been hostile to the abstracting, deracinating forces unleashed by pro-market reformers. That is no longer so clearly the case. After decades of urbanization and atomization, younger generations of Latin Americans who have never known the warm embrace of traditional community or the social-democratic state are more likely to identify their pursuit of freedom with the market, opening a path to electoral success for neoliberal rabble-rousers like Milei, Bolsonaro, the younger Fujimori, and Chile’s José Antonio Kast.

Faced with these developments, the octogenarian Vargas Llosa finally acceded to the indiscriminate mixing of the realms he had long sought to keep separate: the libidinal excesses he identified with literature and the harsh market discipline he had hoped to impose in the political sphere. His enduring hatred of the elder Fujimori, whose political program had ended up being so close to his own, looks in retrospect like an attempt to foreclose the possibility of this eventual synthesis. Perhaps this refusal had lasted only as long as Vargas Llosa needed to retain his conviction in his own vocation. The novel, for him, was a repository for desires that must not be realized in politics. But with his Nobel in hand and his career complete, he could stop worrying and embrace the outcome he had once feared: the appropriation by politics of the irrational urges that should be the stuff of art.