As the 2024 election winds to its conclusion, the race is too close to call, but some things are clear: Donald Trump seems on track to further expand his support with working-class Americans of all races, while Kamala Harris is crushing Trump with the college-educated, especially women. Harris’s most salient issue has been abortion rights; she and her rally-goers routinely chant, “We’re not going back!”—as if Trump were trying to return us to the days of back-alley abortions.

The truth is that Trump’s voters are hoping for a return to that bygone era of 2019, when working-class wages had risen for the first time in 60 years, while inflation was just 1.8 percent. While neither the free-market right nor the Trump-deranged left wants to admit it, Trump was the first American president in half a century to shrink the income gap. And he did it with an intentional policy mix.

There was a tax cut that put money in the pockets of middle- and working-class Americans and a new trade policy—represented by the renegotiation of NAFTA and the imposition of tariffs—aimed at shoring up American manufacturing. But the real mechanism whereby Trump’s economy redistributed wealth from the top 25 percent of wage earners to the bottom 25 percent was his border policy, which radically reduced the number of illegal immigrants entering the homeland through the southern border.

Immigration separates the American elite—the consumers of low-wage labor—from the working class, with whom illegal immigrants compete for jobs. The top 20 percent, who work knowledge-industry jobs that require a command of the English language and the status conferred by a degree, face no pressure from low-skilled immigration but instead benefit from replacing their uncredentialed fellow citizens with much cheaper labor.

The last 50 years have witnessed an upward transfer of wealth from the working class to the credentialed elite, not least through a lax border policy embraced by both parties, though NAFTA and the defunding of vocational training contributed, too. Working-class men have been steadily displaced from the labor force. Meanwhile, more than 50 percent of GDP has been concentrated at the top. Jobs that require brawn and tactile intelligence, that prize teamwork and physical entrepreneurship, have been given to millions of non-Americans, driving down the wages in those industries.

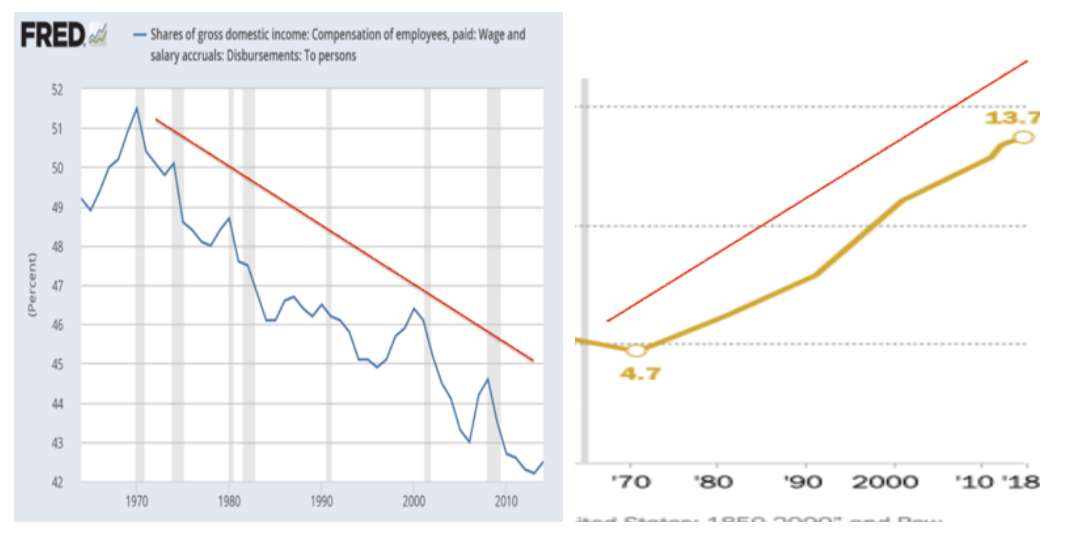

Look at this graph laying out the stagnation of working-class wages since the 1970s:

Now look at this graph laying out the share of the US population that was foreign-born in 2018:

In 2017, the foreign-born share of the US population was almost as high as it’s ever been at 14 percent. The only time it had ever been that high before was during the Gilded Age, a time characterized by profound income inequality. And today, after four years of President Biden’s open border and mass paroling of Haitian and Venezuelan newcomers, the figure is 15 percent. Looking at these graphs side by side, it’s easy to wonder if the two are related:

The reason mass migration is correlated with tanking working-class wages is the ironclad law of supply and demand: The more you have of something, the cheaper it is. This law applies to labor, too. A steady supply of low-wage labor puts power in the hands of employers—and money in the pockets of the ownership class, taken straight from the pockets of the Americans they would have had to pay that money to if they couldn’t employ an immigrant.

“A steady supply of low-wage labor puts power in the hands of employers.”

It’s black Americans—those in the Democratic coalition least likely to see immigration in a positive light—who have paid the highest price for mass migration, resulting in wage losses, family breakdown, and heightened incarceration rates, as Peter Kirsanow told the Senate Subcommittee on Immigration in 2016. When Trump says migrants are taking “black jobs,” he isn’t lying.

This election is about immigration—because it’s an election about class. It’s about whether the next four years should be determined by the struggles of the American working class, whose men have been displaced from work through NAFTA and mass migration, or whether it should be focused on the concerns of rich, educated women, who believe the fall of Roe v. Wade made them America’s true oppressed class.