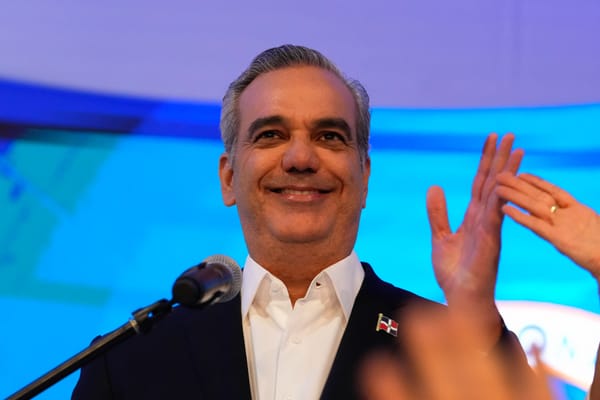

On Sunday, President Luis Abinader secured reelection in the Dominican Republic with a thumping 58 percent of the vote. Along with his Mexican counterpart Andrés Manuel López Obrador, Abinader enjoys some of the highest approval ratings in the democratic world, around 70 percent by some measures. This is all the more surprising given the fact that the Dominican president is a stalwart of neoliberal economic policies. For his admirers, his performance is an enduring triumph for the neoliberal growth model in a period when its previous regional exemplars—notably Chile and Peru—have devolved into stagnation, mass unrest, and political infighting.

The president of a tourism conglomerate before he entered politics, Abinader is worth an estimated $76 million, making him the wealthiest president in the Americas. His ability to enact pro-business policies while maintaining high approval ratings has made him a favorite of investors and foreign leaders, including officials from both parties in Washington who view his administration as a key partner.

The main source of Abinader’s popularity is the flourishing Dominican economy, which has been Latin America and the Caribbean’s star performer in recent years. The island nation has boasted GDP growth upwards of 5 percent since the 1990s, outperforming its resource-dependent peers thanks to its comparatively robust tourism and financial sectors. Even more impressively, growth has remained consistently high even as the rest of Latin America has suffered from another “lost decade” of low growth since the end of the commodities boom in 2014.

For detractors, however, the Dominican Republic is a Caribbean Potemkin village where high rates of growth mask low wages and enduring precarity. Between 2000 and 2020, GDP per capita doubled and now rivals that of Spain during the 1970s. But real wages grew just 17 percent in the two decades prior to 2020 and even declined relative to the mid-1990s. The simple explanation for the ostensible paradox is twofold. Unlike in 1970s Spain, employment growth in the DR has been concentrated in services—mainly tourism—as opposed to more productive manufacturing. Moreover, the DR has an abysmally low minimum wage, around $200-$300 a month.

The Dominican neoliberal order is the product of decades of rule by the rival Democratic Liberation Party (PLD) and the Dominican Revolutionary Party (PRD), whose leaders later defected to found Abinader’s Modern Revolutionary Party (PRM). The uninterrupted democracy that has prevailed since the 1990s is itself a recent phenomenon, preceded by extended dictatorships of Rafael Trujillo and Joaquín Belaguer. However, the two-party duopoly that succeeded Belaguer in 1996 could well be described as a veiled one-party state.

“Dominican politics features neither a hard left nor a hard right.”

On paper, both the PLD and PRM are progressive and social-democratic; both have promoted an unoriginal mix of laissez-faire economic policies coupled with social programs meant to mitigate some negative outcomes. Dominican politics features neither a hard left nor a hard right, with all three candidates in Sunday’s election promoting virtually identical platforms. In Abinader’s own words: “We have the formula of [being] pro-business, but also strong social programs [and] transparency. That’s the only formula that works.”

The result is that a range of policy matters are not open to public debate, and Dominicans mostly elect candidates based on personality and clientelist networks. Abinader was elected in 2020 on an anti-corruption platform after 16 years of PLD rule marred by corruption scandals, including taking bribes from the Brazilian construction conglomerate Odebrecht, whose vast web of graft has brought down multiple governments in the region. His commanding reelection suggests most voters believe he has delivered on his promise of greater transparency, though critics have noted that investigations into PRM officials have been conspicuously lenient, and Abinader himself is suspected to have engaged in significant tax evasion, per the Pandora Papers.

Another source of the incumbent’s popularity is his hard line on immigration. The DR shares a land border with crisis-stricken Haiti, and has pursued draconian policies meant to deter Haitians from entering the country. Just last year, the government deported 175,000 migrants and began construction of a border wall. Given the dire conditions they face, Haitians arguably have a stronger case for claiming asylum than any other migrants in the Americas. But given the scale at which they currently are seeking to emigrate, were the DR to pursue an open-border policy like nearby Colombia, the country’s infrastructure and resources would be strained to the breaking point. It is hardly surprising, then, that voters rewarded Abinader’s restrictionist policies.

Luck and geopolitics have also helped Abinader’s administration diversify the economy. Like Mexico, the DR is currently undergoing a nearshoring boom in manufacturing thanks to rising trade tensions between the US and China. Prior to the Covid pandemic, the country successfully developed a low-tier manufacturing sector in electronic components and medical devices. Since then, the sector has since boomed with record exports, investments, and plans to expand industrial parks and free-trade zones. More importantly, the administration has sought to promote the manufacture of higher-value goods including semiconductors, circuit boards, and auto components. In February, the Japanese firm Yazaki announced that it would invest $90 million to build an auto-parts plant that will employ some 1500 people.

On top of all this, Abinader appears to have finally taken steps to address the country’s pitiful minimum wage. Under the PLD, the minimum wage was increased every two years and in negligible increments in contrast to year-on-year increases during the current term. Just this year, the PRM enacted a 19 percent increase to the minimum wage for large firms (no doubt as an election ploy). The results speak for themselves. With the added benefit of a solid vaccine rollout and a post-pandemic tourism boom, average wages have begun to increase after decades of decline and stagnation. In the four years Abinader has been in office, real wages rose to $450, up from around $300 in 2020. Similarly, GDP growth rose to 12 percent in 2021 and 5 percent in 2022 and 2023 after falling 7 percent in 2020 as a result of the pandemic.

Nonetheless, by some measures, the Dominican minimum wage is still the third lowest in the Americas. Considering the country’s impressive growth, this is disgraceful. Abinader would do well to look to Mexico’s AMLO, who has made raising the minimum wage one of the staples of his administration.

The problem, however, is that the main drivers of investment in the Caribbean nation are precisely the low wages of its workers and its proximity to the United States. Should wages continue to rise, its leaders will be forced to pursue protectionist policies should they wish to further develop the nation’s industrial base. Hence, while the neoliberal model mostly continues to flourish in the DR, in due course the “end of history” will run its course. Whether the Dominican Republic becomes a Caribbean Taiwan or—more likely—a typical Latin American state characterized by dependency and stagnation remains to be seen.