If you follow a certain kind of account on Twitter (I refuse to call it X), you’ve likely seen the posts. An image of a particular type of model—blond, blessed with prominent cheekbones and expensively tousled hair—rides a horse or sails a boat or plays croquet in warm golden light. Befitting the rustic settings in which they’re worn, the clothes are generously cut in muted colors. There’s a lot of tweed, tartan, and perfectly faded denim.

The caption is “Ralph Lauren Nationalism.” Presented without further comment in most cases, the posts belong to a genre that laments the world we have ostensibly lost. Remember an America, they imply, when this fantasia on WASP themes could be found in every glossy magazine and shopping mall in the country. Even if Ralph Lauren’s world was never exactly real, it expressed an ideal of wealth, tradition, and beauty that’s been replaced by gender non-conformists wearing hoodies and yoga pants.

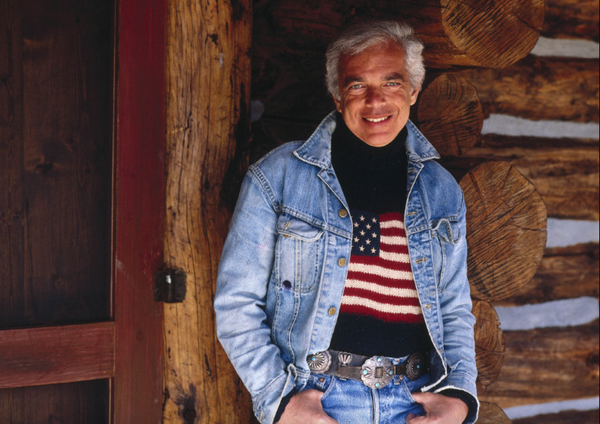

It’s not crazy to search the Ralph Lauren archives for evidence of this vision. For decades, to call something “very Ralph Lauren” has meant crediting it with a specific set of qualities. Expensive, certainly, but broken-in, comfortable. As the brand name “polo” indicates, an old money ideal is at the core of the Lauren imagination. Ralph Lauren’s aesthetic is patriotic, too, in a way that’s become less common among bigtime brands. Ralph Lauren may not have been the first producer to put the flag on his clothes. But he was the first to make it high fashion. There’s also a racial dimension. Although the company has made a point of employing multiethnic models in recent decades, advertising from its ’80s and ’90s golden age relied on white faces.

Yet there’s more to Ralph, who was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom in the last days of the Biden administration, than class drag or period costume, let alone a longing for racial hierarchy. His world isn’t a snapshot of a better past. It’s a pastiche of everything he admires, ransacked and reassembled to order. Brahmin gentility is one of the major inspirations. But so are the West, the Riviera, the safari—and, above all, the way these things were depicted in the movies. The original sources are older and more various. But the combination was only possible in the second half of the 20th century, when America was rapidly moving away from the Anglo-Protestant identity that the “Ralph Lauren Nationalism” memes evoke.

Probably only someone with Ralph’s background could have put the pieces together. Born Ralph Lifshitz to Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe, he had no more firsthand knowledge of London’s clubs or New England campuses than he did of New Mexican pueblos. Far from stopping him, that distance allowed him to select the elements that he found beautiful and discard the burdensome, sometimes tragic histories that produced them. Rather than nostalgia and constraint, optimism and freedom are the defining features of Ralph Lauren’s America. We could use more of that kind of nationalism today.

Ralph Lauren advertising often evokes a pristine Anglo-America of green lawns and cold gin. But when you compare the images to those deployed by other brands that chased the luxury market in the Reagan era you’ll often notice a difference. In an ad for Burberry, say, everything is strictly correct—which means the way that it would have looked in a handbook on proper attire published no later than 1960. Brogues and tweed for the country, Oxford and worsted for the city. It’s paint-by-numbers WASPiration.

“It makes little sense. But somehow it works.”

That’s not the case with Ralph. Despite the appearance of rigorous order, there’s always been something unconstrained, even a bit crazy, about the way the clothes are combined and presented. Patterned nordic sweaters are placed under pin-striped suits. Barn jackets are worn with tropical ducks. Plaids are layered over stripes over checks. It’s a riot of texture and color and glorious confusion of form and function. It makes little sense. But somehow it works.

An indifference to correctness is the special touch that Lauren brought even to the most regimented styles—witness the black dinner jackets he paired with jeans and boots. Like Saul Bellow’s Augie March, another restless city kid who spent time selling haberdashery, Lauren seemed to “go at things as I have taught myself, free-style.” In America, both Lauren and Bellow suggest, the rules no longer apply. Writing like an American means adopting something of Bellow’s linguistic exuberance and intellectual ambition. Dressing like an American means wearing what you want, when you want it. And if that means slapping a nice big flag on your garb, so much the better

It would be reductive to explain Ralph Lauren’s affirmations of freedom by referring to his origins among Jewish immigrants. He presents himself as simply American, not a hyphenate. Still, it is hard to deny that his understanding of the American promise—economic success through personal expression—owes something to the 20th-century Jewish experience.

It’s not just the fact that Jews played leading roles in the shmatte (rag) business, as the garment trade was affectionately known. It’s the way Jews throughout the culture industries adopted symbols of a decaying Anglo-Protestant culture and repurposed them for televisual spectacle and mass-market consumption. By the time Franklin Roosevelt entered the White House, the solitary cowboy, the elegant clubman, the hardy mariner and other American archetypes were disappearing if they hadn’t altogether vanished. But they received another century of life from the movies, from television, and the racks of the local mall.

For all his financial success, Lauren’s real achievement lies among these imagineers. Disproportionately though not entirely Jewish, they cultivated—and promoted—a brand of enthusiastic, optimistic patriotism that combined genuine belief in American ideals with a healthy measure of gratitude for their own success. Once a novelty, that attitude has now lapsed into cliché. With its namesake approaching 90, can “Ralph Lauren” still appeal to American hearts—and wallets?

It’s partly because Lauren has been so influential that his signature pastiche now seems banal. There’s no longer anything surprising about wearing, say, an English-style hacking jacket over a chambray workshirt. When Lauren began to do this in the 1970s, though, it was almost unheard of. Did he think he was lord of the manor or a ranch hand? The answer was both, because Lauren saw no contradiction between the two (so long as they both looked great).

Something similar can be said of Lauren’s extraction of sportswear from its intended purpose. When he started offering them in a range of bright colors—yes, with the contrasting embroidered pony—short-sleeve knits were most often seen on the pitch, court, or links. It was a bit provocative to wear them in less athletic settings and unthinkable to do so while engaged in professional work. Taking the polo shirt out of the country club and into urban streets, Lauren prefigured business casual more than a generation before it became standard. But when he did it, it wasn’t casual in the sense of being thoughtless. Instead, it was a gentle but unmistakable challenge to expectations.

The challenge was not without precedent. Lauren’s taste for combining formal and informal, high- and low-status items can be traced back to the fashions of the 1930s, when male clothing began to incorporate influences from around the world and a wider set of activities. The acknowledged icon of this tendency was Edward, Prince of Wales—later King Edward VII and finally the Duke of Windsor. Bored by correctness and annoyed by the stiff, heavy garments that were then standard, he brought a discernibly American preference for comfort and convenience to then rigorously ceremonial court.

“First you bought the clothes, then you made a life in which they fit.”

What Lauren did was to redeploy this sensibility for democratic capitalism. In their origins, many of the clothes Lauren sold were products of particular ways of life and would have been acquired in order to participate in its characteristic activities and institutions. Lauren reversed the priority—first you bought the clothes, then you made a life in which they fit. That too was part of Lauren’s Americanism. He got rich, realizing his own dreams of grandeur, by making you feel rich.

Yet this kind of shared dreaming may be less appealing than a culture that recognizes almost no standards for dress. Earlier this year, Elon Musk attended a cabinet meeting in a t-shirt, peacoat, and baseball cap. Like the Duke of Windsor’s innovations, Ralph Lauren’s tweaks to convention worked precisely because they were subtle tweaks that left the general standards intact. Rich men today seem to prefer a cruder kind of rebellion.

There’s more going on than personal caprice, though. As the writer Bruce Boyer has pointed out, change in men’s clothing since the French revolution has followed a predictable arc. Garments begin as military gear or sports clothing and are then adapted for less regimented pursuits. After a period of familiarization, formerly casual items become acceptable as business dress. A few decades later, old-fashioned working attire shifts to evening or ceremonial purposes. Finally, the ceremonial wardrobe is relegated to servants, where it may survive in anachronistic glory for a very long time. This cycle is the reason doormen in fancy buildings, as sartorial enthusiast Tom Wolfe observed in “Radical Chic,” dress like 1870 Austrian colonels.

The modern suit is reaching the end of this cycle. Originally known as the “lounge suit,” it has experienced the full transition from a sort of 19th-century athleisure to almost a badge of subordination (that’s the message Musk was sending to the coat-and-tie political appointees). The simple knit polo shirt, workhorse of the Ralph Lauren empire, is a few steps behind. But it’s proceeding along the same trajectory. Not so very long ago, you couldn’t get dinner at a good restaurant wearing one of these things. Among young men today, it’s already seen as a specialty item for jobs, church, or special occasions.

Dispiriting as it is, then, the dominance of such monstrous hybrids as “dress” sneakers is likely inevitable. They’re results of the same process that normalized the soft attached collars, flannel trousers, and suede shoes that the Duke of Windsor introduced to high society and Ralph Lauren used for his tableaux of gentility. All were initially seen as barbaric incursions of the battlefield or playing-field into the drawing room. All were reluctantly accepted and eventually embraced as icons of good taste.

Lauren recognized and profited from the natural lifecycle of menswear. Yet he never rejected the inherent connection between clothes, location, and lifestyle that makes today’s sartorial indifference so opposed to his own calculated jumbles. Rather than just releasing goods onto the market, Lauren tried to create aesthetic settings where it made sense to wear them. At the commercial level, his practice of creating separate, branded areas within a larger department store reflected his understanding that customers didn’t just want to try things on—they wanted to do it in a setting where those shirts or sweaters or jackets make sense.

When Lauren developed his own retail palaces in the 1980s, he chose properties like the former Rhinelander mansion of the Upper East Side of Manhattan that applied the same principle on a grander scale. Lauren’s restaurants, including the Polo Bar in Midtown Manhattan, are popular partly because they create a tiny stage on which his style of dressing looks appropriate, rather than for any merits of the cuisine. It’s said that Lauren even provides a location-appropriate wardrobe for visitors to his residences around the world. Nothing could be farther from, say, John Fetterman’s insistence on dressing for the Senate floor as if he were joining a pickup basketball game.

Lauren is fond of insisting that he’s not interested in trends. Actually, the details of his products are less consistent than this claim suggests. Lauren got his start as an independent operator selling napkin-width neckties that were a striking contrast to the slim lines of the Mad Men era. As admiring observers recognized, it was brilliant marketing strategy that allowed Lauren to build up a full product line. Once you bought a fat tie, you needed a new shirt with a taller and wider collar. A shirt like that wouldn’t look right under the tubular “sack” coat then favored by American men. So you also had to buy a new suit featuring broader shoulders, wider lapels, and more shape around the waist. Lauren launched his career, in short, as a vendor of the kind of 1970s gear that is still the butt of jokes. An unintentional revelation of Ralph Lauren: In His Own Fashion, a 2019 coffee table book by the clothier Alan Flusser, is just how trendy some of this stuff was.

The days of lapels that touched the shoulders passed, and Lauren had worked the exaggeration out of his look by the 1990s. Although it receives less attention in authorized chronicles of the Ralph empire, this was also the period when Polo was adopted as the aspirational brand of hiphop, then emerging as the world’s dominant popular music.

Rappers loved the bright colors and vaguely decontextualized functionalism of Polo goods. Many were also enthralled by the outsider-to-insider narrative that Ralph Lauren embodied. Unable to afford retail prices, some resorted to felony-level shoplifting. In the song “Bury Me With the ‘Lo On,” larcenist turned musician Thirstin Howl III, described his obsession:

During eternal sleeping

I want to look the same as when you last see me breathing

P.O.L.O waterproof Goretex pants with velcro

Official ’Lo sailboats, iron buckle, script jacket

Silk scarf around my head, make sure that it matches

I don't care if I’m buried in a vacant lot

A cardboard box or under a pile of rocks

BURY ME WITH THE ’LO ON

It was likely impossible to remain at this peak. In the 21st century, the Ralph Lauren enterprise was hit by three developments that made the founder’s vision less enthralling.

First, financial pressures following the company’s IPO in 1997 encouraged globalization of production and decline in quality. Ralph Lauren had originally used British cloths and American and Italian factories, yielding expensive products of uniformly high quality. As they sought to increase supply and profit margins, the company seemingly shifted to cheaper materials and shoddier construction, especially on lower margin items. Even when not immediately obvious, these changes eliminated some of the magic that could be felt even when it couldn’t be precisely identified.

Second, the dominance of business casual—ironically promoted by Ralph himself—helped strip away the old mystique. Rather than the athlete’s closely-fitted sheath—or even the rapper’s oversized appropriation—the polo shirt became the shapeless uniform of middle management. As an unforeseen result of their very success, Ralph Lauren’s clothes became what Ralph had always rejected: clothes your dad wore to an office he hated.

Finally, attempts to stay relevant led the brand astray. Sometimes associated with the Ivy League Look, Ralph Lauren’s real inspiration lay in Golden Age Hollywood, where no one seemed to do anything so dull as study for exams or hold a job. Inspired by the Duke of Windsor, the heroic dressers of the screen abandoned the tight, architectural garments of their Edwardian fathers in favor of softer fabrics and looser fits. After its Ron Burgundy phase, Polo settled on a relaxed, grownup silhouette that acquired shape from the drape of the cloth rather than the wearer’s physique.

Popular in the ’80s and ’90s, this cut was an outlier to the preference for very slim proportions that took over around the turn of the 21st century. Without abandoning the old inspirations for fabric or color, Ralph Lauren products shrank until they could be worn successfully only by teenage ectomorphs. The constrictive results made an unfortunate contrast to those classic advertising campaigns orchestrated by the photographer Bruce Weber. The key to the success of Weber’s images wasn’t so much the beauty of the models, although that was considerable. It was that they looked so relaxed in the soft textures and accommodating proportions.

These developments weren’t necessarily bad for business. The company is now worth more than $7 billion and Lauren’s personal fortune may be even larger. Unlike other giants of the mass-market designer era, the name also retains some cachet. “Ralph Lauren” still means something while, say, Pierre Cardin has been relegated to bargain bins. And while the pandemic struck another blow against intentional dressing by encouraging work from home, the women’s side of the business is reportedly strong.

Today, though, Lauren’s vision is a victim of its own success. Juxtapositions of high and low status, appeals to natural freedom, and romantic self-creation are no longer challenges to some imagined status quo. Partly because Ralph’s sensibility has been so influential, they are now the shared idiom of the establishment.

The character of that establishment has changed, too. Like Lauren himself, the descendants of the great migration of Jews and other “Ellis Island” immigrants triumphantly entered mainstream institutions. In the short term, this shift gave new vitality to dying forms. Without Lauren’s intervention, for example, the kind of traditional American clothing developed by his old employer, Brooks Brothers, would likely have disappeared. Contrary to assumptions about seamless tradition, original owners are not always the best conservators of their heritage.

Originality doesn’t last forever, though. In the end, the cultural innovators of Lauren’s generation produced a new generation of thoughtless, and often graceless, privilege. Even the rappers who once aped the lifestyles of the rich and famous have themselves become moguls, donors, and arbiters of fashion. It’s not exciting to see them dressed in ’Lo when they could afford to buy everything in the store. Ralph Lifshitz from the Bronx got his start rejecting rules in favor of his sense of what looked great. But that vision has itself become a cliché attached to its own brand of superficially polished but essentially vulgar snobbery.

A revival of Ralph Lauren nationalism wouldn’t just cling to the archetypes he developed, then. To recapture the old excitement, some new dreamer would have to find ways to challenge, but also to delight, the America he helped to create. Beautiful as it is, just putting on the old tweed coat won’t get us there. We’re still waiting for a new, and doubtless very different, Ralph Lauren.