Recent years have seen much talk of a “New Right,” and Donald Trump’s return to office promises increased influence for this loosely defined faction. But in politics nothing is ever entirely new. This is far from the first time a renewal of the right has been attempted; it’s not even the first time such an effort has framed itself as seeking to inaugurate a “postliberal” age. Indeed, there have been as many new rights as there have been new lefts or new liberalisms to counter. In particular, our present partisan and intellectual turmoil recalls Britain just before and during World War I, a period that witnessed at once the “strange death of liberalism” and a “crisis of conservatism.” An especially memorable writer to come out of this moment, if certainly not the best-known, was Thomas Ernest Hulme, who sought, like many self-proclaimed new-rightists today, to give a harder edge to the conservatism he inherited.

Hulme’s life is well summed up by a biographer as a “short, sharp” one. His entire oeuvre can be read in a few days. He is that rare figure who had considerable influence without either writing very much or, if we’re being frank, writing anything very original. And yet the extraordinary force and concision of Hulme’s writing, and the distinct spin he put on otherwise familiar notions, gives his thought a special vividness.

“Like our last two presidents, he abstained from alcohol.”

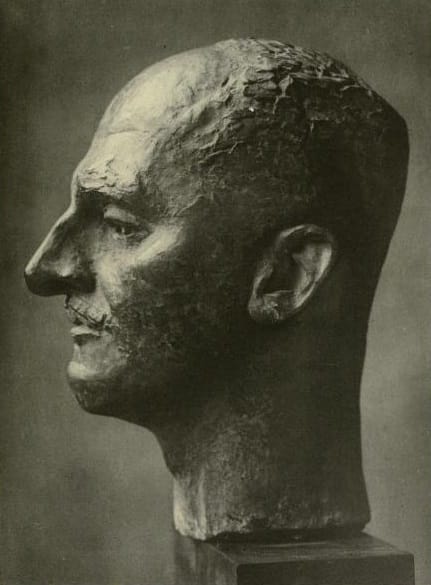

It’s not always true that literary style mirrors personality. But in Hulme’s case it certainly did. He had an imposing build, which provided a physical basis for the dominant role he played in the febrile world of London clubs and cafés. He was aggressive and contumelious, getting into brawls and making threats, including in response to (what he judged) odious opinions. His libido matched his stature, a fact that contributed to his being sent down from Cambridge not once but twice. And perhaps most remarkably, he did all this without liquid courage; like our last two presidents, he abstained from alcohol. These qualities reappear in Hulme’s prose, which exhibits in a high degree what the critic Stefan Collini calls “the pathos of manliness.” At the same time, Hulme conforms to the commonplace that people study what they aren’t—that mathematicians can’t add, economists are bad with money, moral philosophers have a lot of vices. This was true of Hulme, too. Discipline and order grounded the thought of this disorderly and undisciplined man.

Hulme was born in 1883. After his tumultuous stints at Cambridge and various peregrinations he wound up in London, where he found himself at the center of an avant-garde reacting against what it saw as Victorian respectability and prudery. A poet (though one who wrote very little poetry) and art theorist, he had a considerable influence on the movement we now know as modernism—above all on T.S. Eliot, who saw him as a kind of prophet. Hulme insisted that politics and aesthetics were linked. He thought one could rather easily read off someone’s views on pressing political questions from his preferences in sculpture or novels. (This resonates again today, when cultural fandom often collapses into partisan allegiance.) Hulme largely conceived of politics, like art, in terms of taste. “Temperament” or “attitude” had a great role to play in both artistic and political affinity, he surmised. And aesthetic revulsion shaped his objections to contemporary politics.

Like Eliot, who took the idea from him, Hulme saw the ascendant “romanticism” he wanted to dethrone as encompassing both art and politics. The features that he found contemptible in romantic art and literature—its exaltation of the spontaneous personality against the societal barriers opposed to its full expression, its cult of the individual over tradition, its equation of accomplishment with “breaking of rules,” its pretentiousness and fluffery, its emotivism—carried over into political life. “I object to the sloppiness which doesn’t consider that a poem is a poem unless it is moaning or whining,” he wrote. “The thing that I think quite classical is the word lad. Your modern romantic could never write that. He would have to write ‘golden youth,’ and take up the thing at least a couple of notes in pitch.” Similar gripes animated his political thought. Notably, in all this he found overlap with the left, which also included many thinkers whose animus toward modernity was driven by a sense of its ugliness, its egotism, its destruction of valuable ways and practices.

Hulme, though, was an unabashed Tory. When it came to politics, he has usually been seen as a detached thinker, removed from the intricacies of public debate. And certainly, his political writing does take place from 30,000 feet, so to speak. But even the most abstract theories are incited by real-world events. In Hulme’s case, his political ideas were forged in response to the great constitutional crisis that unfolded from 1909 to 1911. Throughout the middle of the 19th century, the Liberal party had seemed to be the natural party of government, setting the intellectual tone of the country and establishing England’s reputation as the liberal nation par excellence. But from the mid-1880s the Conservatives enjoyed a couple decades of electoral success. In Hulme’s view, however, this parliamentary ascendancy never came close to dislodging liberalism as the de facto public philosophy of Britain; and liberalism was the name taken in politics by the romanticism Hulme hated.

In any case, the Conservatives’ good stretch came to a crashing halt in 1905, when rifts over free trade split the party. (A new wave of Conservatives wanted to institute a tariff policy, breaking with their decades-long accommodation to the greatest symbol of mid-19th-century liberal triumph.) The Liberal governments that came in, moreover, were of a self-consciously “New Liberal” type that sought to couple such traditional liberal goals as toleration, eradication of privilege, free exchange, and the rule of law with a more redistributive and interventionist state. In 1909 this New Liberal government, pressured by the rise of Labour, which would soon supplant it atop the party system, introduced “The People’s Budget.” This legislation, which would set the foundations for the modern welfare state, met steep opposition from the Tory-leaning House of Lords. The Lords rejected the bill multiple times, precipitating two general elections in the year 1910. The tumult culminated (under threat from the king to pack the upper house with new peers) in the Parliament Act, 1911, which removed the right of the Lords to veto money bills and limited it to a two-year suspensory veto on all other bills.

The result of these turbulent years was a radical change in the nature of the British state. As even one self-proclaimed “old liberal” declared, what had transpired was a “revolution” that destroyed “our last effective constitutional safeguard,” handed an “absolute legislative dictatorship” to temporary partisan majorities, and in effect birthed “a new constitution.” Hulme was even more apoplectic. He wrote that the legislation of 1911 installed “unrestrained Single-Chamber Government” and thus brought the triumph of “pure democracy,” from which would come the downfall of “civilization,” the “gradual end of things.” It was this turmoil that gave rise to his political thought proper.