Waste Land: A World in Permanent Crisis

By Robert D. Kaplan

Random House, 224 pages, $31

In college, I attended a talk by the writer Robert Kaplan. As I recall, I was less interested in hearing what he had to say than seeing how he dressed, how he carried himself. At the time, my almost unconscious assumption was that the kind of career I wanted would be just like Kaplan’s. He was, as I saw him then, the thinking man’s Paul Theroux. He seemed to have a book for every part of the world: Balkan Ghosts was followed by Eastward to Tartary; his other books ranged from Togo to Somalia to Pakistan to Turkmenistan. The books were always thoughtful, serious, and well-received. But somewhere along the line—between Mediterranean Winter: The Pleasures of History and Landscape in Tunisia, Sicily, Dalmatia, and Greece and Imperial Grunts: On the Ground with the American Military from Mongolia to the Philippines to Iraq and Beyond, and a dozen similar titles —it occurred to me that Kaplan’s wide-ranging travels always brought him back to the same place.

“While this thesis captured real tendencies, it was also conveniently vague.”

In each new locale, Kaplan found more evidence for “The Coming Anarchy,” an idea he proposed in the mid-1990s, in effect a somber antithesis to Francis Fukuyama’s “End of History” and the ambient optimism of the era. As Kaplan wrote in 1994, “Sierra Leone is a microcosm of what is occurring, albeit in a more tempered and gradual manner, throughout West Africa and much of the underdeveloped world: the withering away of central governments, the rise of tribal and regional domains, the unchecked spread of disease, and the growing pervasiveness of war.” While this thesis captured real tendencies, it was also conveniently vague. Anytime something went wrong somewhere in the world—disease, war, civic unrest, resource depletion—Kaplan was there to say that it was yet another harbinger of the “coming anarchy.”

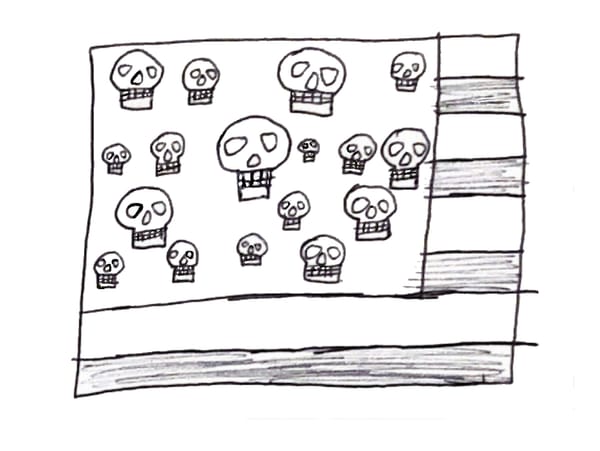

Kaplan’s latest book, Waste Land: A World In Permanent Crisis, reprises this thesis with fresh data points—notably Covid, the Ukraine War, and the Oct. 7 attack. Kaplan’s basic point is inarguable: The world is beset by all sorts of problems not foreseen by the more Panglossian prophets of globalization in the 1990s. But there is no reason to believe tossing out Fukuyama in favor of Kaplan will lead to a more prudent foreign policy. The reckless overextension of US power under George W. Bush’s administration is often seen as reflecting the Beltway elite’s overconfidence in the forward march of democracy and capitalism. But the arch-doomer Kaplan also supported invading Iraq, and the outlook that led him to that stance remains intact in his new book. This is no accident. Viewing the crises we face—a resurgent Russia and China, conflict in the Middle East, pandemics, climate change—as portents of the “coming anarchy” puts us in a mindset of seeing existential dangers everywhere, and relying on force to fix them.

The idea of Waste Land is that, globally, we are in the equivalent of Weimar Germany. “The entire world is one big Weimar now,” Kaplan writes, “connected enough for one part to mortally influence the other parts, yet not connected enough to be politically coherent.” This sounds dark and dire, and seems to mirror the general sense we have of the West being governed by feckless leaders, but not even Kaplan is entirely convinced by the analogy.

In Weimar Germany, a parliamentary democracy lost confidence in itself and permitted the ascension to power of an anti-democratic autocrat through democratic means. Kaplan doesn’t think we face this outcome. “I see no Hitler in our midst, or even a totalitarian world state,” he accurately writes. “But don’t assume that the next phase of history will provide any relief to the present one. It is in the spirit of caution that I raise the subject of Weimar.” Having Kaplan extend and then retract these arguments (this isn’t the only time this happens in the book) is like watching a slow-handed dealer try to pull a three-card monte trick.

The fact that Kaplan is alarmist and muddled doesn’t mean he’s altogether wrong. When I got over my exasperation with his mode of argumentation, I found myself agreeing with him more often than not. I agree that we have spent the last 30-odd years on a holiday from history and that history is roaring back; I agree that great-power politics is what matters most and the airy notion of creating a global liberal order has distracted us from the underlying realpolitik between Washington, Moscow, and Beijing; I agree that the institutions charged with maintaining the “rules-based international order” have been almost entirely useless.

“You don’t read Jeremiah for his geopolitical insights.”

I also agree with the initial insight that propelled “The Coming Anarchy”: Namely, that the interconnectedness of the world means that problems in apparently far-flung, resource-deprived places are “first-world problems” as well, and that what happens in, say, Sierra Leone often portends crisis elsewhere. And I am sympathetic to Kaplan’s general premonition that something very terrible is on its way and that our inability to create a viable global order or even to care about the rest of the world will come back to haunt us. At some level, I don’t even mind the indeterminacy of his premonitions: You don’t read Jeremiah for his geopolitical insights.

But, at another level, I do mind, greatly. Kaplan is supposed to be writing in an analytic mode, and his inability to be specific can’t be overlooked. At various points in Waste Land, Kaplan name checks, among others, the following crises: the proliferation of nuclear weapons; the spread of revolutionary ideology; the breakdown of the nation-state; paradoxically, although no less perniciously, the use of precision weapons by over-powerful nation states. For Kaplan, no silver cloud is without its dark lining. “The world is getting better and this makes governing it more difficult,” he even writes at one point.

Needing a thesis grand enough to take in all the aforementioned problems, Kaplan comes up with—believe it or not—anti-Semitism. To make this point, Kaplan has to abandon another of his grand unified theories, outlined in his 2012 book The Revenge of Geography, which emphasized the inevitability of conflict between Eurasia’s “Heartland”—the landlocked powers at the continent’s center—and its coastal “Rimland.” But now, he claims, common hatred of Israel has brought these former rivals together. “The Heartland and Rimland divisions just don’t capture the flavor of what is happening,” Kaplan writes in jettisoning his old theory. “Anti-Semitism does: since in its latest iteration it has been ignited by the war between Israel and Gaza and has since spread throughout the West, to the Russian Empire, and to China.”

Arrayed against this axis of Jew-hatred are liberalism, democracy, decency, good table manners, and remembering to call one’s parents—and all of those are anchored, as it so happens, by Israel. “Israel stands at the heart of this global geopolitical war,” Kaplan writes. “That is because Israel hasn’t really wavered.” If the entirety of geopolitics can be reduced to a struggle over anti-Semitism, no one could possibly be more righteous than the Jewish state, while any aggression Israel displays toward its nemeses is just a sign of its wholehearted alignment with the causes of democracy and liberalism. As he puts it: “Israel, although its population may be divided on many issues, is absolutely united about the need to militarily defend its territory, to defeat Hamas, and to neutralize Iran and its proxies.” The strategic implication is clear: The fickle, wavering West needs to adopt Israel’s singleness of purpose and join in the great geopolitical struggle.

Kaplan has been down this road before. As the Bush administration set its sights on Iraq in late 2001, he met with White House officials to help draft an internal report advocating the invasion. The following year, he took to the pages of The Atlantic to drum up support for the war, promising it would offer America “a position of newfound strength” in the Middle East. Kaplan has written that he later suffered clinical depression from reflecting on his advocacy of the war, and it is moving to read his accounts of why he got things as wrong as he did. In Waste Land, Kaplan achieves a contemptuous distance from the invasion, calling it “a truly unnecessary and disastrous war of choice” which he blames on a “dearth of wise and cautious leadership” in Washington.

But the habit of sweeping pronouncements dies hard, and Kaplan is back at it in Waste Land, tacking the Axis of Evil onto the Eastern Bloc, with some indeterminate Hitler analogies thrown in for good measure—no matter that Kaplan once enjoined himself to remember that “every villain is not Hitler and every year is not 1939.”

The truth is that he may not be wrong in pivotal points of his analysis—that we are in a new Cold War, that much of the Israel-hating Middle East has made common cause with Russia and China, that there are incommensurate value systems between the different geopolitical blocs—but these are serious questions and the framing of them has immense stakes. What Kaplan offers is a revival of the Manichean thinking that informed the most shameful episodes of the Cold War and the “either you are with us or you are with the terrorists” schematic of George W. Bush.

If we see “the coming anarchy” everywhere, we also tend to allow ourselves to believe—as Kaplan has in the past and still seems to today—that extraordinary employments of force, no matter how cruel, are necessary evils. Precisely because the dangers Kaplan highlights are very serious, they deserve more sober and judicious analysis than he is capable of providing.