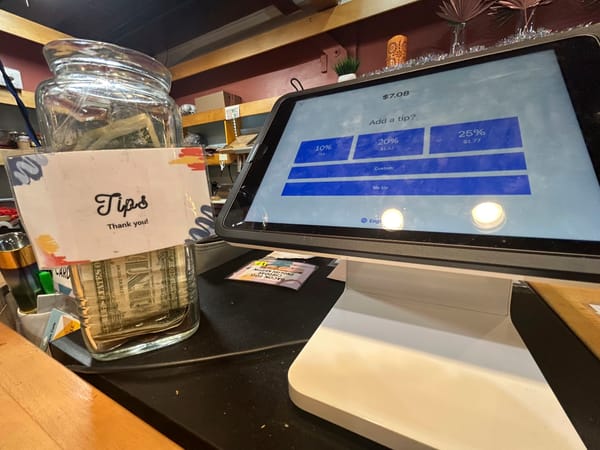

To buy something in the United States these days is to tip—or at least to be asked to tip. The once common jar next to the register has been replaced, or supplemented, by a flip of an iPad, as the guy behind the counter glances over to see which of the four options the patron taps to go along with her coffee, burrito, or scented candle. Once a passive way to compliment good service, tipping has become a ubiquitous barometer of one’s ethics and disposable income.

No wonder, then, that 3 of 4 respondents to a recent survey say tipping is “out of control.” A few years ago, non-food service sectors started trying to get in on a rush of good will for “essential workers” in the depths of the pandemic, those tips have been sliding, and some are beginning to worry that tipping fatigue will extend all the way to full-service restaurants.

But tipping has become an issue this election year not because of consumers’ exasperation, but because the two presidential candidates are both trying to appeal to voters who rely on tips at work. First, Donald Trump, campaigning in service-industry-dominated Las Vegas, vowed to exempt tips from taxation. Kamala Harris then followed with her own version of the one-line policy proposal—a firm promise in a platform mostly lacking them. So far, neither has added more detail, but a bill introduced by Republican senators in June offered some clues about what such a policy might look like. The National Restaurant Association, the industry group that has long supported efforts to block any increase in the minimum wage, has backed that proposal, while Democratic-leaning economists and policy wonks have mostly opposed it.

The NRA’s support for the proposal isn’t hard to understand. In essence, as some liberal economists have pointed out, a federal tax break would function as a pay raise that restaurants don’t have to cover themselves, so management would be less inclined to increase staff wages. It would also incentivize recategorizing workers who don’t currently rely on tips as tipped workers.

“All but seven states have a minimum wage that’s lower for tipped workers.”

This last prospect is most likely in states that retain a split-level minimum wage. At present, all but seven states have a minimum wage that’s lower for tipped workers than for other workers. In Texas and Nebraska, for instance (two of the fifteen states that lack a state-level minimum wage to override the federal standard), an employer only has to pay tipped workers a pitiful $2.13 per hour, assuming tips bring their hourly income up to or above the federal minimum of $7.25. By reclassifying currently untipped workers as tipped workers, management could shift even more of the burden of paying their staff onto customers.

But at a full-service restaurant, where staff survive on tips, all that can sound like a problem for tomorrow when today is hard enough as it is.

Recently, I asked a server at a mid-priced full-service chain restaurant in Northern California whom I’ll call Vanessa about her thoughts on the recent proposals. She was eager to talk, although taxes were just one of a few burdens she’d faced as of late. She had worked at another restaurant owned by the same franchising company for years, until it closed. Before getting transferred to her current place of work, her managers promised an extra working day and a wage increase. The raise turned out to be a dollar per hour and the promised extra hours never materialized, resulting in a net loss of income. Not having to pay taxes after all that sounded nice, she said. When I asked whether she feared her employers would pay her less if taxes on tips were lifted, she wasn’t too concerned. Her employers weren’t the sort of people to wait for changes in federal policy to take advantage of her.

Tips have been subject to federal tax since 1938, but it wasn’t until 1982, when Ronald Reagan’s tax cuts led to a mad search in Congress for ways to make up for lost revenue, that the federal government began pursuing them in earnest. A sharply reduced capital-gains tax meant hedge-fund managers and corporate executives contributed less to federal coffers; restaurant servers and other tipped workers were enlisted to make up some of the difference.

Still, the limited array of payment methods available to most restaurants allowed for some reporting gaps that a typical server could work to his or her advantage. Credit cards were expensive to process; the few restaurants that accepted them tended to be the kinds of places that served steak and lobster, where tabs—and tips—were high. Most tips at most restaurants went to servers in the form of cash left under dirty plates, and in most settings, servers could keep or report them at their discretion.

It’s a different picture today. Credit and debit cards are most people’s preferred means for settling a bill, and many places accept nothing else, making it easier than ever for both restaurants and tax authorities to track servers’ income. In 2008, Americans paid for slightly more than half their purchases on a card. Fifteen years later, nearly two thirds of payments were made on a card, according to a study by the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta.

What hasn’t changed is the source of that income: customers. That arrangement gives restaurants plenty of ways to quell any agitation for higher pay without having to put their own money on the line.

One option is to tell employees to upsell their customers: Vanessa and a colleague who later joined us said managers frequently told staff to urge customers to buy sides and upgrades. Larger bills, they reminded staff, mean bigger tips. Another, at least at chain restaurants, is to look the other way when servers take cash tips for themselves. Though employees are required to log cash tips, Vanessa said management said nothing when she and her coworkers pocketed money left on the table. “Everyone does it,” she said of the practice.

Still another approach taken by managers is to combine and redistribute tips among staff—in effect raising some servers’ income in lieu of increasing it for everyone. For much of her shift the day I talked to her, Vanessa was the only server on duty. Nonetheless, store policy required that she split her tips among the entire staff—a rule she abhorred. “Why should I have to share my tips if I’m working here myself?”

“For now, and for the foreseeable future, tip your server in cash.”

Vanessa is just one server, of course. But her experience is hardly unique. For her and many of the four million tipped workers in the United States, tips aren’t a bonus for a job well done. They are an essential component of a survivable income. Lifting taxes on tips might give managers a reason to forestall a future pay raise, but in an industry dead set against paying employees more under any circumstances, it’s hard to imagine them needing the excuse.

For now, and for the foreseeable future, tip your server in cash.