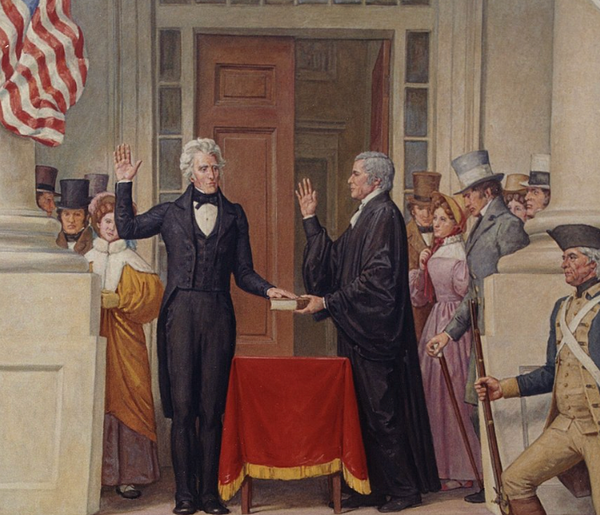

No 19th-century political figure provokes a stronger emotional reaction among contemporary Americans than Andrew Jackson, the nation’s seventh president and the first to be nominated by the Democratic Party. He was a man of the Tennessean frontier, and was identified in the public mind with his humble pioneer roots despite amassing wealth, land, and more than a hundred slaves. Around the time he was elected, property qualifications for voting were eliminated in most states in the country, and he was swept into power by a mass of “common people.” These newly enfranchised voters saw him as their champion against the nation’s ruling interests.

Jackson’s legacy as president is defined by two grand actions. In 1832, he vetoed the renewal of the Second Bank of the United States, a federally chartered financial institution that favored large capitalists over farmers and craftspeople. He also urged the removal of the Cherokee from their homeland in the Southeast, against the ruling of the Supreme Court, in order to make way for white settlement. In a sense, both actions reflected his populist commission.

Earlier generations of left-leaning historians recognized the mixed legacy of Jacksonian populism, but regarded his struggle against moneyed elites and on behalf of workers and farmers as a crucial phase in the realization of America’s democratic promise. More recently, however, it has become controversial in the academy to suggest Jackson was anything other than a genocidal maniac. This evolution reveals a precipitous loss of sympathy among academic historians and educated liberals for the “common people” with whom Jackson identified his presidency.

“Pundits across the political spectrum found reasons to link Trump to Jackson.”