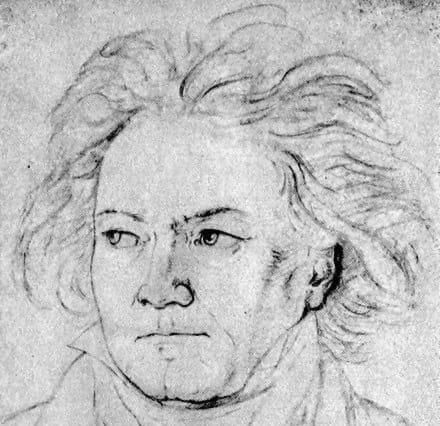

The Catholic Beethoven

by Nicholas Chong

Oxford University Press, 336 pages, $88.99

Historians love influence, yet genius eschews it. The whole point of genius is its singularity. Or as Beethoven once put it to his patron: “What you are, you are by circumstance and birth. What I am, I am through myself. Of princes there have been and will be thousands. Of Beethovens there is only one.” Historians, then, face an uphill battle when trying to chart the influence on a true genius, not least because most readers frown upon too much context, and instead prefer something closer to defiance of it, at least when it comes to a figure like Beethoven.

“Historians face an uphill battle when trying to chart the influence on a true genius.”

Whatever one makes of Beethoven’s singularity, nobody can deny his good fortune in living through a particularly interesting period in German history. Almost an exact contemporary of Hegel, Beethoven (1770–1827), is generally seen as having taken up Kant’s imperative to shun authority and dare to think for himself. It has gone mostly unquestioned that Beethoven, like the good subject of the era he helped to define, dropped his childhood religion and wrote modern music for a new, secular age.

This assumption comes under scrutiny in a new and impressive study by the musicologist Nicholas Chong. As he writes in The Catholic Beethoven, “The habitual attempts to distance [Beethoven] from Christianity in general, and Catholicism in particular, have thus served a broader desire to present the composer and his music as quintessentially modern.” Chong supplies a largely convincing counter-narrative that “Beethoven and his religious works were influenced by the German Catholicism of his era to a greater extent than has long been thought.”