At the height of the Cold War, Soviet spies and saboteurs were imagined to be lurking in every nook and cranny. In recent years, Western governments and media outlets have once again become fixated on the dangers of foreign propaganda. Ever since the twin shocks of Brexit and the election of Donald Trump in 2016, just about every inconvenient bit of political news has been attributed—however implausibly—to the machinations of Vladimir Putin, with his infinite armies of bots and all-powerful “disinformation” apparatus.

This anxiety reached self-parodic levels after Canada’s House of Commons offered a standing ovation to Yaroslav Hunka, a Ukrainian veteran of the Waffen-SS. In response, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau warned that the scandal made clear once again why “it is important to push back against Russian disinformation.” This seems like a strange association to make: It is hardly as if the Russians forced Canadian lawmakers to honor Hunka. If they, or anyone else, report that Canada accidentally honored a Nazi veteran, that is simply the truth of what happened. How would it qualify as “disinformation”?

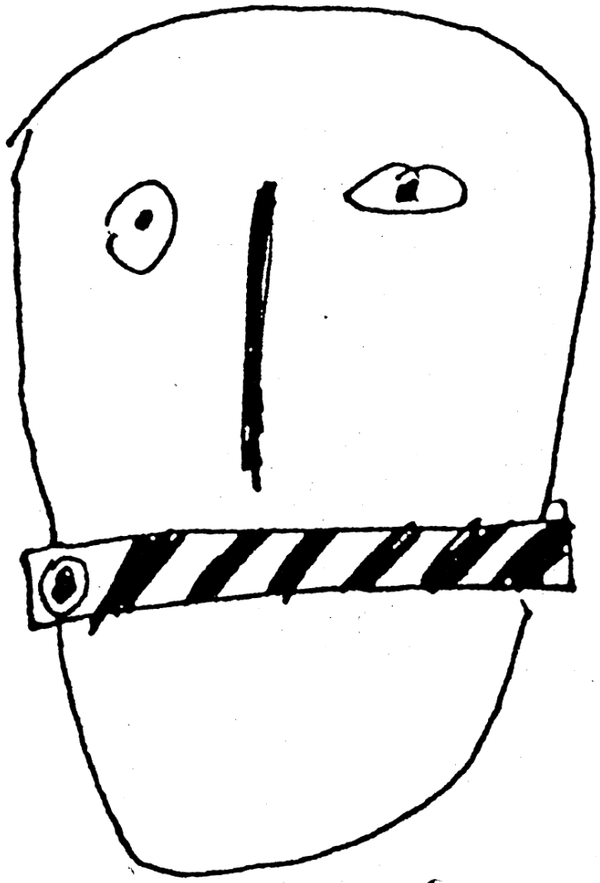

“The need to protect the official narrative requires the erasure of reality.”

The answer is that there has been an inversion in the official Western understanding of what truth, propaganda, and disinformation are. Amid the initial panic about online misinformation and disinformation, we were often told we had entered the “post-truth” era. This turns out to be true, but not in the way it was intended. We are now seeing what “post-truth” looks like: a situation in which the need to protect the official narrative requires the erasure of reality.