Donald Trump’s statements on foreign policy are remarkable in horrifying warmongers and pacificists alike. Those who insist on the necessity of American military intervention in every conflict around the globe find Trump appallingly skeptical. He has suggested that the expansion of US military alliances into Eastern Europe might have provoked Russia into its invasion of Ukraine, an observation that many noteworthy foreign policy analysts consider not only wrong, but offensive. He has stated on the record that Taiwan is very close to China and very far away from us. He has even said that he would prefer to make a deal with America’s enemies rather than condemn them as evil.

At the same time, Trump delights in boasting about the awesome lethality of American military power. Those who regard him as a fascist were not reassured by his recent comments about annexing Canada, Greenland, and the Panama Canal—still less his refusal to disavow military force in obtaining these goals. It is easy to imagine him repeating the phrase “settler colonialism” without realizing that it is supposed to be a bad thing.

Writing in The Atlantic, David Frum argues that Trump’s reelection represents a rejection of the worldview that presidents of both parties have upheld since World War II, which sees the United States as the generous guardian of “the liberal world order … the center of a network of international cooperation—not only on trade and defense, but on environmental concerns, law enforcement, financial regulation, food and drug safety, and countless other issues.”

The worldview Frum describes actually emerged only in the 1990s, when American policy commitments became unconstrained by the existence of a peer competitor. But Frum captures both its ideals and illusions well, particularly in his warning that Trump threatens to turn America “from protector nation to predator nation.”

No nation, in the world as it is, can exist as a protector without also being a predator, a fact that some of America’s allies, like Germany and Japan, have reason to understand better than Americans themselves. But an apex predator does not need to go around baring its teeth. Indeed, in the absence of a significant rival, such a creature might even begin to mistake its own terrifying will with an impartial system of laws and voluntary cooperation.

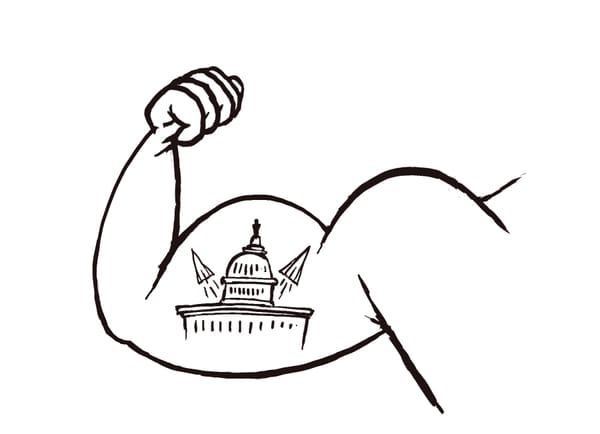

“Trump seems to be signaling a revival of older foreign-policy principles.”

Trump’s rejection of this worldview makes him seem both more belligerent and more strategically modest than any of his recent predecessors. If the United States arrived at global preeminence by adopting the favorite aphorism of Theodore Roosevelt—“speak softly and carry a big stick; you will go far”—Trump seems to have adopted something like the opposite motto at a moment when multiple adversaries have begun to test the limits of American power: “Shout menacingly and retreat to your vital interests.”

This attitude may be a radical departure from the recent past, but it is not unprecedented. In his inimitable style, Trump seems to be signaling a revival of older foreign-policy principles—vaguely familiar today as Manifest Destiny and the Monroe Doctrine. It may be worthwhile to recall these discarded ideas, if only as a reminder that a departure from the foreign policy consensus of the last 30 years is not the same as a rejection of the traditions that made us who we are.

What eventually became known as the Monroe Doctrine consisted of three related principles formally announced by President James Monroe in 1823. 1) “The American Continents … are not to be considered as subjects for future colonization of any European power.” 2) US abstention from European conflicts. And 3) European interference with any of the American governments that maintained their independence would be regarded “as the manifestation of an unfriendly disposition toward the United States.”

This boils down to the idea that Europe should stay out of the Western hemisphere, and the United States should stay out of Europe. But only the second half of that formula described an active policy of the United States government in its early years. The first principle of European noninterference amounted, at first, to an idle sentiment, unsupported by any genuine threat much less a binding military commitment.

The early republic was active in drafting and signing treaties for all sorts of purposes, including treaties meant to promote its own security and that of other independent American republics. But after winning its own independence, the United States consistently avoided any military alliance until NATO in 1949. As Monroe’s Secretary of State John Quincy Adams famously said, America “is the well-wisher to the freedom and independence of all. She is the champion and vindicator only of her own.”

“Manifest Destiny was the unofficial corollary to the Monroe Doctrine.”

Manifest Destiny was the unofficial corollary to the Monroe Doctrine, the powerful national impulse animating the formal pronouncement. The Doctrine’s implication that the United States was the predominant power in the Western Hemisphere was a mere pretense in 1823, but it was a pretense Americans were then willing into reality. The policy of avoiding any entangling alliances was crucial in reassuring European governments that America’s territorial ambitions would not upset the balance of power on their own continent. No one quite predicted how quickly the upstart republic would grow from too petty to fear to too formidable to oppose.

The phrase “Manifest Destiny” wasn’t coined until 1845, but the territorial ambitions it describes were evident in the new nation from the very beginning. Indeed, it is not an exaggeration to say that expansionism was once the most powerful force in American culture. It was perhaps inevitable that colonists from an island nation would become intensely conscious of the fact that they inhabited a continent, and become possessed by a feverish desire to acquire as much of it as they could.

British efforts to check the relentless movement westward was a crucial cause of the American bid for independence. After the revolution, western settlement exploded. More land west of the Appalachian Mountains was occupied in a single generation than in the prior two centuries of colonization combined. Expansion was less a policy than a raw popular energy that the new national government struggled to control.

But the process was immeasurably facilitated by one of the most brilliant political innovations of the founding era. Whereas European powers held their territories as dependent provinces, peripheries permanently inferior to the imperial metropole, the United States established a new and revolutionary conception of empire. The national government guaranteed settlers the same rights as other Americans and promised that new states would enter the Union “on an equal footing with the original States, in all respects whatsoever.” This innovation allowed Americans to combine what earlier political philosophers regarded as incompatible aspirations—the grandeur and power of a vast empire and the political freedom of small republics. It also allowed Americans to equate their greedy hunger for land with the lofty goal of spreading liberty itself. And it explains Americans’ continuous bafflement with Canada, which has always preferred to remain a dour, irrelevant appendage to this grand experiment rather than join it as equal partners.

In the 1790s, the idea that anyone then living would see the admission of American states along the Pacific Coast would have seemed almost as ludicrous as the prediction that anyone alive today will see senators from Mars take their seats in the national capitol. Yet the idea of the American Union as a continental “Empire of Liberty” quickly seized the imaginations of visionary leaders. The ablest and most enthusiastic early exponent of America’s continental destiny was John Quincy Adams, who succeeded Monroe in the presidency in 1825. It might take centuries, Adams predicted in 1820, but the boundaries of the American Union would eventually extend to the Pacific Ocean. Europe must be made to “find it a settled geographical element that the United States and North America are identical,” he wrote.

Only in the 1840s did the goal of stretching the republic from sea to shining sea become official government policy. By then, expansionist aspirations had become consumed by the conflict over slavery, and John Quincy Adams had gone from the foremost champion of Manifest Destiny to its most outspoken opponent.

The president who made Manifest Destiny a reality was James K. Polk. Polk’s territorial ambitions were more nakedly covetous than any of his predecessors, even Andrew Jackson, and he combined them with a blunt willingness to fight.

Consider a political map of North America in 1845, the year Polk took office: The most significant recent change was the Republic of Texas, which had won its independence from Mexico in 1836. Some southerners wanted to annex Texas because it would expand the power of the slave states. But other southerners relished Texan independence, hoping it might become the gravitational center of a new slaveholding confederation, encompassing the American southeast, the Caribbean, and Latin America—and completely free of moralizing Yankees. Great Britain also made overtures of an alliance with the Texas Republic. At any rate, here was the first spot where the political map was sure to change soon, perhaps dramatically.

Of course, annexation of Texas by the United States would instantly create diplomatic tensions with Mexico, which had never recognized Texas’s independence. This presented either a grave problem or a brilliant opportunity, depending on how one looked at it.

Far to the northwest was the contested territory known as Oregon. This included the present states of Oregon, Washington and Idaho, as well as parts of Montana and Wyoming. It arguably also included all of western Canada up to the Alaska boundary as well. President Polk was elected on a platform demanding it all, a fact not well-calculated to produce calm negotiations with the British. Here was another cartographic ambiguity that suddenly became an acute diplomatic crisis.

And finally, there was the vast region of northwest Mexico, a region the Mexican government only tenuously controlled. This included two provinces, California and New Mexico. But no one knew where the boundary between them was, or even what might be found in the vast desert between the settlements at either extreme.

Just a year earlier, in May of 1844, the first telegraph message in history was sent between Washington, DC, and Baltimore. That same summer, the same telegraph line brought news of Polk’s nomination by the Democratic convention in Baltimore.

The world was rapidly shrinking under an ever-expanding network of steamships, railroads, and telegraph wires—the most significant changes in the pace of travel and communication in millennia, since men learned to write, sail and ride horses. European powers were beginning to recover from the exhaustion of the Napoleonic Wars. Britain, France, Spain and Russia all had ambitions of reversing their waning presence in Western Hemisphere. At this critical moment, the United States must either boldly seize its destiny or surrender it forever. At any rate, that is what President Polk believed.

Adams complained that Polk had “no wit, no literature, no gracefulness of delivery, no philosophy.” The great historian Bernard DeVoto concurred only in part, writing that “Polk’s mind was rigid, narrow, obstinate, far from first-rate … He was pompous, suspicious and secretive … But if his mind was narrow it was also powerful and he had guts.” No president was ever more successful in obtaining the goals with which he began his administration. Ralph Waldo Emerson combined revulsion and awe in sizing up Polk and his expansionist allies: “They have a sort of genius of a bold and manly cast, though Satanic.”

“Manifest Destiny” was a catastrophe for the Native Americans, whose lands were overrun at an accelerating pace. It encompassed an unspeakable amount of greed, dishonesty, hypocrisy and corruption. It meant bullying weaker neighbors, displacing and even exterminating established communities. And it often meant the spread of human slavery.

But it has become fashionable to pretend that these evils were the whole of it. Older historians were more likely to cheer the spread of American ideals and institutions across the continent. “Manifest Destiny,” Arthur Schlesinger wrote, “signified a glowing faith in democracy and a passionate desire that it rule the world.” John O’Sullivan, who coined the phrase in 1845, wrote that the mission of America was to spread “freedom of conscience, freedom of person, freedom of trade and business pursuits, universality of freedom and equality.”

Listen to the young Walt Whitman—that most American poet and, incidentally, an outer borough boy—sounding almost Trumpian in his exuberance for Manifest Destiny. It is from American democracy, Whitman wrote, “with its manly heart and its lion strength spurning the ligatures wherewith drivellers would bind it—that we are to expect the great FUTURE of this Western World! A scope involving such unparalleled human happiness and rational freedom, to such unnumbered myriads, that the heart of a true man leaps with a mighty joy only to think of it!”

As a young Whig, Abraham Lincoln nearly destroyed his political career by opposing Polk’s war against Mexico. A bit later, he sarcastically observed that the American expansionist “owns a large part of the world, by right of possessing it; and all the rest by right of wanting it, and intending to have it.” That sarcasm vanished, however, when President Lincoln explained why the American people must persist in fighting a horrific civil war rather than let the vast American Union be torn in two. “That portion of the earth’s surface which is owned and inhabited by the people of the United States is well adapted to be the home of one national family, and it is not well adapted for two or more,” Lincoln wrote.

“Manifest Destiny intensified the sectional tensions that produced the Civil War.”

Lincoln delivered these remarks in his Second Annual Message to Congress in February 1862. The Congress he addressed enacted a rush of legislation that organized and incorporated the great West into the Union—an act creating the first transcontinental railroad, a homestead act, and an act creating land grant colleges to develop and disseminate agricultural sciences in taming these wild frontier lands. Manifest Destiny intensified the sectional tensions that produced the Civil War, but it also endowed Americans with a sublime faith in the grandeur and significance of their national existence. And without that, the Union would not have survived the first shot fired in anger.

It isn’t easy to separate Donald Trump’s outsized personal idiosyncrasies from the broader political movement he represents. A candid interpretation of his record must begin with acknowledging that much of it consists in erratic improvisations and meaningless hyperbole. Yet Trump’s most consistent rhetorical theme also supplies the most obvious key to his political significance. He is the first president in decades to identify national greatness as his singular goal and purpose; the first to state bluntly that the interests of the United States are distinct from the interests of friends and adversaries alike; and the first to distinguish the nation’s security interests from a set of abstract values that all well-meaning nations supposedly share.

“Any effort on our part to reason the world out of a belief that we are ambitious,” John Quincy Adams wrote in 1820, “will have no other effect than to convince them that we add to our ambition hypocrisy.” Whatever vices the world may impute to the leadership of Donald Trump, hypocrisy is not likely to be among them. And it is in this sense that Trump represents a revival of the blunt national exuberance behind the Monroe Doctrine and Manifest Destiny.

Trump’s preoccupation with national greatness is the theme that unites even such incongruous and improbable promises as a magnificent wall across our southern border with Mexico and the complete annihilation of our northern border with Canada. Both promises reflect a renewed preoccupation with the nation as an entity embodied by its territory. Law, commerce, and culture are all capable of transcending national boundaries, creating organizations, networks and communities that blur the lines between sovereign states. But the territory that gives a nation its tangible presence on a map also necessarily sets it apart from the rest of the world. A nation may gain territory, or lose it, but it cannot share it.

“Trump has reasserted the primacy of territorial boundaries.”

Trump has reasserted the primacy of territorial boundaries as a fundamental feature of the United States’ collective identity. And he has done so after decades of globalization, and relative global stability, seemed to be dissolving those boundaries to the point of irrelevance.

At the same time, Americans have always inspired and flattered themselves with a belief that their nation carries the universal aspirations of mankind. But this has traditionally meant contrasting the glorious achievements of America with the tyranny and barbarism prevailing everywhere else. The generous idealism resonates as a prideful popular boast.

Trump is not capable of echoing the loftiest aspirations of American patriotism, but then the unrefined ambitions of common people have always been the animating force of American democracy. “America,” Emerson once wrote, “seems to have immense resources, land, men, milk, butter, cheese, timber and iron, but it is a village littleness—village squabble and rapacity characterize its policy.” The village squabble, energized by a lusty appetite for freedom and elevated by the combined continental grandeur of those participating in it—if intellectuals tend to dismiss this national pastime as parochial pettiness, Trump represents a roaring correction. He understands that a nation’s sense of its destiny, like its territorial boundaries, binds a people together only by setting them apart.