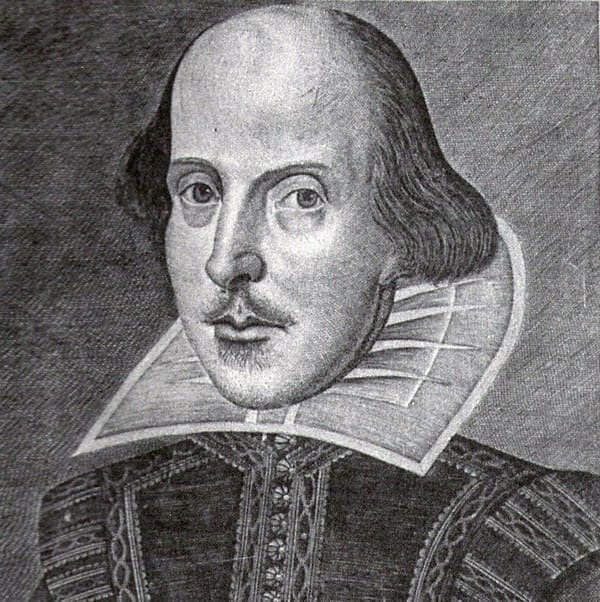

For more than a century, a small but persistent faction has argued that Edward de Vere, the Earl of Oxford and a prominent courtier of the Elizabethan age, is the real author of the works attributed to William Shakespeare. “Oxfordians” deny that William Shakespeare—a man of humble birth, limited means, and modest education—could have written the plays published under his name. They regard the high-born, well-traveled, and consummately cultured de Vere as a far more credible candidate.

Recently, the Oxfordian theory has experienced an unexpected revival within New York’s hotly debated and much-derided “downtown scene.”

“Oxfordianism has taken on a meaning that transcends its roots in fringe scholarship.”

Thanks to De Vere Society founder Phoebe Nir, who has memed Oxfordianism into cultural consciousness, the writer Curtis Yarvin, and an anonymous essay in the Mars Review of Books, aided by ambient social-media chatter, Oxfordianism has taken on a meaning that transcends its roots in fringe scholarship (albeit a fringe scholarship championed by figures as diverse as Mark Twain, Sigmund Freud, and, more recently, actor Mark Rylance). De Vere has been reborn as a rallying point for, and signifier of, a certain kind of unorthodox conservativism.

Defending Shakespeare’s authorship, and speaking from my own experience as a playwright and occasional director of the Bard’s plays, I engaged Yarvin in a public debate this past fall in Manhattan. The results of the debate aside, I have since come to realize that the historical or factual aspect of the supposed “authorship question” (I don’t think it’s a question at all) is immaterial to the symbolic power of Oxfordianism.

Behind the renewed interest in Oxfordianism is a longing for an alternative political order in which creativity reflects and reinforces a highly stratified society. The fact that the greatest genius of the English language came from a modest background is a stumbling block to those who believe that only the right kind of elites are capable of guiding our politics and culture. By contrast, the claim that Shakespeare was written by an aristocrat serves to neutralize the anarchic potential of creative genius, so that art serves sovereign power, rather than disrupts it. In short, Oxfordianism appeals to the post-pandemic right not simply because it is part of a general trend of questioning institutional truths, but because it aligns with an alternate vision of institutions.

The current right-inflected version of the Oxfordian theory of authorship states that in order to write about kings and queens, princes and princesses, the court, foreign places, the law, philosophy, you have to have been raised among kings and queens, and traveled the world, and studied the law, and studied political theory, and studied the classics, and studied archery, and whatever else. There is an almost one-to-one relationship between input and output, and shockingly little opportunity, in this model of how writing works, for imagination and iteration. If you haven’t been formally trained in a subject, you can’t represent it in fictional form. Genius is a matter of having learned everything there is to know, and being able to reproduce it in the form of poetry or drama or fiction.

This theory entails that only those with the finest education can give the most elevated expression to the human spirit. It goes without saying that a good education carries countless advantages, but the Oxfordian theory relies on an excessively rigid view of intelligence and how creativity works. What might be called “based Oxfordianism” sees the human mind as being something like the current version of AI: in many ways impressive, but also bounded and mechanical. There is no room for that leap, which we identify with genius, beyond the expected and received.

Despite its association with the right, therefore, the revival of Oxfordian theory aligns, more than it realizes, with the elite liberal politics of the World Economic Forum, the Democratic National Committee, and every other gated political community that claims to know better, think better, and ultimately rule better than ordinary people.

But the greatest irony of the current Oxfordianism is that many of its proponents don’t necessarily hail from the elite of the elite, but are rather bright kids from unremarkable backgrounds, whose precocious intelligence has carried them to prominence. There is some sort of misrecognition at work here, where people who share something with Shakespeare, the unkempt genius, are unable to recognize that, preferring to see themselves in a pampered aristocrat.

One of the great joys and pleasures of possessing a natural, rather than an artificial, intelligence is the ability to transcend one’s origins by iterating from the tiniest amount of experience. Humans can invent powerful fictions from the barest inputs, and turn a wisp of cloud into castles in the sky. No one demonstrates this better than Shakespeare, whose genius vaulted him past not only the Earl of Oxford, but countless other men with better blood, higher learning, and wider experience.

Indeed, Shakespeare’s childhood in the countryside, and his youth as an apprentice writer in London and the courts, gave him a wider view of human nature than the one he would have received were he bound up in the comparatively narrow world of the English aristocracy. This is the real Shakespeare: the harried, overworked theater manager, the potentially suspect husband and father, whose later works express his deep regret at not having spent more time with his daughters. This man, granted a glimpse of court life, but without any promise of safety or security, is a far more inspiring—and democratic—figure.