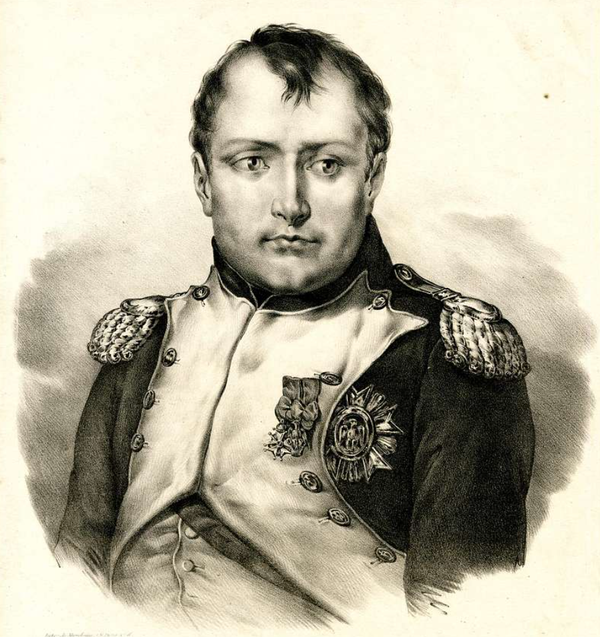

Napoleon is back in the news—and so is Bonapartism. Even as Ridley Scott’s movie Napoleon storms theaters, to be bloodied by critics, Steven Spielberg reportedly is working on a TV series about the French autocrat and conqueror. Meanwhile, Bonapartism or Caesarism—the dream of a tribune authorized by acclamation of the masses taking on corrupt bureaucrats and legislators on behalf of those same masses—is flourishing in some parts of the American left and right. While progressives have called on President Biden to circumvent congressional gridlock by issuing executive orders and invoking the 14th Amendment, conservatives have mounted a more comprehensive case for presidential power.

Adherents of the “unitary-executive” theory claim that most if not all statutory limits on the control of the federal civil service and independent agencies by the president are unconstitutional limits on executive power. They also argue that the president has the right to appoint and remove all employees of the administrative agencies, an idea summed up by the acronym RAGE, which stands for “retire all government employees.”

The late Jeane Kirkpatrick impressed on me the wisdom of a rule that she was taught by the midcentury political scientist Harold Lasswell: “When designing a constitution, assume that your worst enemies are in power.” The Lasswell rule is often ignored by those who think their party will be in power for the foreseeable future. In the United States, fervent supporters of what Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr. called “the imperial presidency” tended to be Democrats during the period when Democrats controlled the White House from 1932 to 1968, with the exception of Eisenhower’s two terms as president. During that era of hegemony by New Deal Democrats, conservatives tended to defend the prerogatives of Congress, as James Burnham did in Congress and the American Tradition (1959). Legal theorists on the right first pushed the unitary-executive theory in the period from 1968 to 1992, when only Jimmy Carter’s single term interrupted a succession of Republican presidencies.

Beginning with the election of 1992, Democrats have won the White House five times and Republicans only three times—twice by winning the Electoral College while losing the popular vote, in 2000 and 2016. In the same period, in the 14 congressional elections between 1992 and 2022, Republicans have won control of one or both houses of Congress in every voting year except those of 1992, 2006, 2008, and 2020. Rational Republicans in the present era of Democratic presidential predominance and Republican congressional competitiveness should therefore want to minimize the discretionary power of the presidency, while maximizing the authority of Congress.

Partisan strategy aside, under Donald Trump or someone else, the road to right-wing Bonapartism in the United States is blocked by a lack of both legitimacy and legality. Let’s start with plebiscitary legitimacy, the claim that an election shows that the leader is the sole true representative of the majority of the nation.

Napoleon Bonaparte and his nephew Louis Napoleon, aka Napoleon III, made sure that they received overwhelming majorities of the votes in their plebiscites. In the 1852 national referendum in France that turned President Louis Napoleon into Emperor Napoleon III, 97 percent voted in favor, mirabile dictu. His uncle and role model did even better, garnering 99.3 percent of the vote in the 1804 French national referendum that promoted Napoleon Bonaparte from First Consul to Emperor of the French.

“Plebiscitary democracy isn’t democracy at all—it is elective dictatorship.”

Supporters of plebiscitary rule would have a hard time claiming a popular mandate for a candidate who wins fewer than half of the votes in an election. But in 2016, Trump received only 46.1 percent of the popular vote, meaning that 53.9 percent of American voters wanted somebody else to be president and cast their votes accordingly. In 2020, Trump’s share of the popular vote grew to 46.8 percent, still short of a majority. Plebiscitary legitimacy, then, doesn’t exist in the case of presidents like Trump in 2016 and George W. Bush in 2000 who lost the popular vote but won the electoral college cannot claim to represent a popular majority.

Even an American president who, like Napoleon III, won 97 percent of the popular vote, wouldn’t therefore become the sole legitimate representative of “the people.” Because “the people” don’t exist in any modern nation as a homogeneous entity whose members share the same values and policy preferences. The United States is a continental country with the third largest population in the world, and is extremely diverse in terms of class, region, religion, ethnicity, and politics. Social diversity can only be represented in a representative legislature that mirrors its major divisions, not by a single elected official. The same would be true for a single party that claims to represent the whole on the basis of winning a plurality or majority of the vote. Plebiscitary democracy isn’t democracy at all—it is elective dictatorship.

Legality, like legitimacy, works against Bonapartism in America—at least a Bonapartism of the Republican right. Since the Reagan years, a faction of legal scholars and pundits on the right have promoted the unitary-executive theory, on the basis of Article II, Section I of the federal Constitution: “The executive Power shall be vested in a President of the United States of America.” The barrier to a broad reading of the phrase “executive power” is found in Section 2 of the same article:

The President shall be Commander in Chief of the Army and Navy of the United States, and of the Militia of the several States, when called into the actual Service of the United States; he may require the Opinion, in writing, of the principal Officer in each of the executive Departments, upon any Subject relating to the Duties of their respective Offices, and he shall have Power to grant Reprieves and Pardons for Offences against the United States, except in Cases of Impeachment.

“Legality, like legitimacy, works against Bonapartism in America.”

The president “may require the Opinion, in writing, of the principal Officer in each of the executive departments, upon any subject relating to the Duties of their respective Offices…” What? Isn’t the power to ask the secretary of State or the secretary of the Treasury what they are doing implicit in the grant of the executive power in Section 1? Apparently not. Evidently, the framers of the Constitution thought that the danger of heads of executive departments ignoring the president was so great that they had to write an obligation on their part to report to him into the Constitution itself.

The framers were right to be concerned. During the 19th and 20th centuries, executive agencies worked closely with long-serving members of congressional committees, while mere presidents came and went. In the 20h century, the term “iron triangle” was used for the close connection between a federal agency, a congressional committee, and a special interest group.

American presidents have often felt excluded from this ménage à trois. While he was still a political scientist, future President Woodrow Wilson denounced “congressional government,” which he defined as government by congressional committees. Herbert Hoover, Franklin Roosevelt, and Harry Truman all backed proposals for a more centralized civil service answerable directly to the president. Congress said no, preferring to multiply independent agencies under close congressional oversight. Many are organized as bipartisan regulatory commissions like the Federal Trade Commission.

The Supreme Court in Humphrey’s Executor v. United States (1935) rejected the unitary-executive theory and held that Congress could restrict the power of the president to remove members of the FTC and similar independent agencies except in cases of “inefficiency, neglect of duty, or malfeasance in office.” In other cases, the high court has distinguished between purely executive officers and those executing quasi-legislative or quasi-judicial functions.

This makes sense. As commander-in-chief of the armed forces, the president must have the authority to be sure that his orders are followed by being able to fire anyone in the chain of command, from the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff to a disobedient private. But this has nothing to do with, say, the Federal Communications Commission debating in public and then setting standards on the basis of a delegation of rule-making power from Congress to the commission. No president could possess the attention span and knowledge of detail necessary to personally supervise all regulations issued by all federal agencies.

Note that we are talking about congressional delegations of authority by statute to executive agencies, like the Environmental Protection Agency. Not even the most extreme proponent of the unitary-executive theory of presidential power would claim that the phrase “executive power” would give the president inherent authority to regulate the environment by executive order, if a future Congress were to abolish the EPA and eliminate any role for the federal government in environmental policy.

Even if the president could claim a mystical mandate from the voters to override detailed agency regulations at will, presidential appointees or civil servants—perhaps in league with business or nonprofit lobbyists—would draft the executive decrees that the president would sign, perhaps without reading them. While some lobbies might benefit, there is no reason why American citizens in general would favor transferring federal rule-making authority delegated by Congress to independent agencies that hold public hearings and solicit public comments to shadowy cliques of partisan presidential appointees in the West Wing of the White House and the Eisenhower Executive Office Building.

Fortunately, while Andrew Jackson and Teddy Roosevelt and Richard Nixon, along with Trump, have engaged in Bonapartist rhetoric at times, only one authentic Bonaparte has come to power in America: Charles Joseph Bonaparte, the Baltimore-born grandson of the first Napoleon’s brother Jerome. Teddy Roosevelt appointed him, first, secretary of the Navy and, later, attorney general of the United States. (Legend has it that TR liked the idea of giving orders to a Bonaparte.)

Unlike today’s advocates of RAGE, however, the American Bonaparte wasn’t a Bonapartist. He helped to found the National Municipal League, which favored a merit-based civil service to replace the patronage system that advocates of the unitary-executive theory would end up reviving. And as attorney general, the American Bonaparte created another institution that, like the civil service, is despised by the RAGE right: the Bureau of Investigation, known today as the FBI.