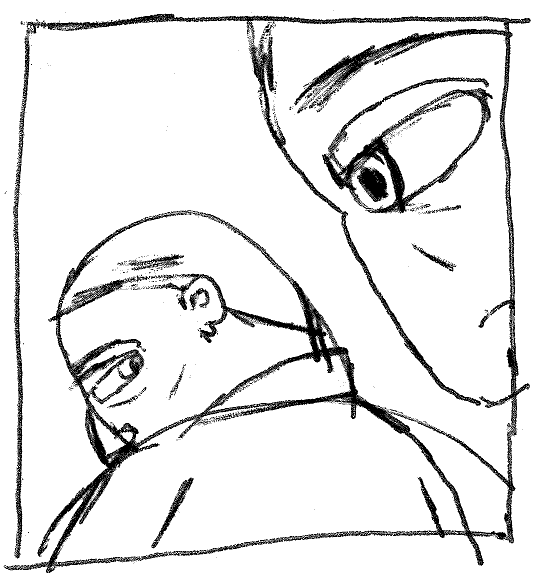

A doctor rushes to the side of a patient who has just collapsed on the way to the toilets in the emergency wing. He checks for signs of life—pulse, circulation, breathing. He has never seen the patient before. How serious, he wonders, could this be? The doctor calls out: “Does anyone know anything about her?” The senior nurse, who has just come over, looks shocked.

“Him!” she practically shouts at the doctor. “You refer to that patient as him!”

And the doctor thinks to himself: “So I’m supposed to check the patient’s pronouns before I check his pulse.”

This story—I heard it from the doctor himself, David Mackereth—illustrates a salient point about what I call the Thing, that combination of postmodern identity theory, religious fervor, pseudo-therapeutic “empathy,” dogmatic moralism, private bullying, and ritualized public humiliation which has swept through Western societies over the last decade. The Thing may seem an irresistible force, but in truth, it can only take possession of an institution if that institution has already lost its identity.

If an organization knows and cherishes its history, if it empowers its members, if they understand their role in society, their vocation and contribution to the common good—then it is significantly less likely to be captured by the Thing.

But when you talk to people in the National Health Service, or the labor movement, or the police, you hear an eerily similar account of what has happened: a forgetting of the social role that used to give that institution meaning; a transfer of power from those on the front line to a remote administrative class; vocation edged out by bureaucracy; pronouns instead of pulses.

David Mackereth’s faux pas outside the hospital toilets foreshadowed a more consequential disagreement. In 2018, he resigned from a role at the Department of Work and Pensions after being ordered to use “preferred pronouns.” Two employment tribunals have ruled that Dr. Mackereth’s beliefs, though rooted in his Christianity, aren’t protected by equalities legislation. The courts will surely have to revisit this subject. But of course, such matters aren’t only decided in court: They are also decided by the climate of fear in British life, not least in the NHS.

“If everybody who agreed with me on the issue of transgender pronouns had spoken up,” Mackereth says, “this would all be over in an instant.” But people are thinking of their kids, their mortgages. “A lot of the nurses, for example, who are treating men on women’s wards felt very strongly about it, but they wouldn’t speak up, because they knew that they would be sacked.”

What has made for such compliant souls? That brings us to another story: how the NHS, instead of nurturing the doctor-patient relationship as the heart of its identity, has prioritized the relationship between doctors and administrators. “When I qualified 30 years ago,” Mackereth recalls, “we just did medicine. We saw patients. And doctors were considered powerful.” They were also, he concedes, often unaccountable. Something needed to change. But the resulting bureaucratization has been overwhelming.

“A doctor today feels like a cog in a system.”

“It’s incredible, the number of different organizations, committees, managers, who can come down to your department and say, ‘You’ve got to do this, you’ve got to do it in 48 hours,’” says Mackereth, who still works in the NHS. “People who aren’t actually seeing the patients have enormous power. And sometimes there will be one organization which comes down and says, ‘You’ve got to put a lock on that door because it’s dangerous,’ and then there’ll be another organization which comes down the next day and says, ‘You’ve got to take that lock off the door because it’s dangerous.’” Eventually, he says, you get used to doing as you’re told.

A doctor today feels like a cog in a system, and that goes not just for locks on doors but for social and political questions. “I feel like I’m in a sea of ideologies. Some of them are competing, some of them are synergistic, and I don’t seem to have a voice at all.”

If the NHS has downgraded the medical vocation into a small cog of a vast administrative machine, what has happened to the labor movement is no less strange: Unions appear to have forgotten about solidarity. Compact readers will be familiar with Paul Embery’s acute criticisms of British trade unionism, its shift from a working-class movement into a mouthpiece for progressive liberalism. Deindustrialization took away the unions’ importance; Margaret Thatcher’s anti-union laws restricted their field of action; and, casting about for some new identity, they were swallowed up by the professional-managerial class.

“Unions appear to have forgotten about solidarity.”

Embery speaks from experience: He was on the executive council of the Fire Brigades Union until he gave a speech at a pro-Brexit rally in 2019, whereupon the union publicly denounced him and removed him from his role. (Unlike Mackereth, Embery was later vindicated by an employment tribunal.)

Embery joined the union around 25 years ago, and tells me he has seen a significant narrowing of acceptable opinion. Back then, “if you were in your workplace, and you were under threat of being sacked for voicing the wrong opinion, the unions by and large would have supported you. Whereas now they tend to run a million miles from you.”

Once again, that lack of free expression is closely related to a lack of internal democracy. Though Embery continues to speak warmly of his own union, he believes its leadership has become “very authoritarian, very arrogant, and [has] treated the union almost as its own private property.” When Embery joined, many union members had years of serious political experience under their belts. “They’d been involved in different movements, they’d been through the big fights with Thatcher.” Some remembered the tempestuous 1970s.

Whether you agreed or disagreed with these old warhorses, Embery says, they knew how to organize. When they retired, “we lost a layer of people who were able to challenge and hold the leadership to account and argue for a different philosophy, and organize within the union.” The movement has suffered from a steady depoliticization.

Or more precisely: It has suffered from the removal of politics into the hands of activists whom everyone else is too afraid to criticise. Embery cites a recent conversation with a senior union official, who attends his fire brigade’s monthly meeting of the Diversity and Equality Committee. “What he said is, the whole thing is like a neverending treadmill.” Once, these meetings were focused on identifying and battling discrimination—“all very virtuous, laudable stuff.” But now, Embery’s acquaintance observed, the committee finds itself hunting for something to do. “What they never do is meet and say, ‘We’re doing OK at the moment, we don’t really need any new initiatives now.’ And the more you look for the next thing to do, the more and more some of those things are becoming more radical and extreme. That’s when you get to the point of pronouns on badges and stuff.”

There is an unignorable resemblance between Mackereth’s story and Embery’s: the same identity crisis within an institution, the same disempowerment of the rank and file, the same sudden dominance of the Thing. But nowhere has this process been more spectacular than within the police.

Campaigners tend to be made, not born. This is especially true of Harry Miller, a businessman—and, crucially, former copper—who in 2019 was told by police to stop tweeting about gender issues, and placed on a “non-crime hate-incident” register. He was so shocked by his treatment that he challenged it in court, eventually winning a major, if only partial victory, and co-founded the organization Fair Cop, which exposes police overreach.

Like Mackereth and Embery, Miller laments what has happened to the institution he once knew. “I always understood,” he says, “that the police have to be utterly apolitical, and not even give the impression of being political.” In the 1990s, if you were on duty at a political march, “you were tasked to be careful not even to accidentally walk in time with the music, in case it gave the impression of being supportive.” A short pause before a characteristic Miller punchline: “Now, of course, the police provide the fucking band.”

This is scarcely an exaggeration of what has happened to British police forces, whose public image has been redefined by a series of sinister and occasionally comic forays into thought-policing and earnest identitarianism. As well as arresting people for everything from street preaching to causing anxiety with one’s tweets to silently praying to filming an arrest, officers have staged a new theater of the absurd: taking the knee at BLM demos, displaying a billboard reading “BEING OFFENSIVE IS AN OFFENSE,” handing out flowers to female passersby on International Women’s Day, unveiling rainbow police cars, rainbow light displays, rainbow flags….

“The politicization of the police has been a top-down process.”

For Miller, the politicization of the police has been a top-down process. He points to the rewriting of the police oath in 2002. Once, it embodied a certain ideal of public service:

I, […] do solemnly and sincerely declare and affirm that I will well and truly serve Our Sovereign Lady the Queen in the office of constable, without favor or affection, malice or ill will; and that I will to the best of my power cause the peace to be kept and preserved, and prevent all offences against the persons and properties of Her Majesty’s subjects.

There is a simplicity to this. It sums up, very plainly, the high calling of the police officer and points to the virtues—diligence, loyalty, honourableness—needed to carry out one’s duties. But in 2002, a new pledge was added to the text: “upholding fundamental human rights.” That, on Miller’s telling, was a Trojan Horse. It allows police officers to declare that “trans right are human rights” and imagine that they are merely upholding their oath. The fact that human rights are a political term, whose range is highly disputed, goes overlooked. “Is the Second Amendment a universal human right? If you ask an American, they probably think it is. But you’re not going to find any police officer going, ‘Gun rights are human rights,’ are you?”

The other change was, naturally, the creation of a new bureaucratic hierarchy. In 2012, the then-home secretary, Theresa May, decided the police needed to be professionalized, via a new College of Policing which would re-found police work around “evidence” and “research.” “The answer to the question, ‘Why do we do this?’ will never be, ‘Because we always have done it that way,’” May proclaimed. “It will be, ‘Because that is what the evidence tells us works best.’” In other words, a new hierarchy was being created, with authority to reshape police work across the land.

The college bears the brunt of Miller’s criticism. “They are leading the way in politicization,” he says. “They claim that they are writing guidance that the average bobby can understand,” but in fact they have obscured a policeman’s real duties with new, more ideologically contentious ones.

Confirmation of Miller’s point comes in a remarkable analysis published last year by the think tank Civitas. It is the closest study I have ever read of the ideological corruption of a 21st-century British institution, and it shows how the college has imposed, from the top, a new way of understanding the police’s role. Soon after the college was created, a new Code of Ethics appeared, backed up with the threat of disciplinary sanctions, which required officers to “actively seek or use opportunities to promote equality and diversity.” Later, the college invented the “non-crime hate incident”—a ludicrously broad category, under which 20,000 people a year were officially categorized as haters despite having committed no offense.

Moreover, the college has empowered activists. It made itself accountable to something called a “super-complaint,” a special category of complaint which can only be made by one of 23 campaigning organisations. It helped to produce the “race action plan”: The plan’s scrutiny board is led by a barrister, Abimbola Johnson, who believes officers should be more “woke” (her term) and who during the George Floyd protests recommended that we “rethink what we classify as criminality in the first place. Until you no longer need to fund a police force.”

The Civitas report details the extraordinary number of ways in which activists can claim authority. One is “affinity groups”: associations of police officers categorized by religious, ethnic, sexual, and other identities. “These groups,” the report notes, “are always the go-to people for diversity and inclusion managers and will often fall little short of dictating internal policy.” There are also innumerable “independent advisory groups” that instigate a constant cycle of meetings with Pride Month organizers and diversity campaigners. And then there are the big campaign organisations like the omnipresent Stonewall, here as elsewhere treated as an infallible source of practical wisdom.

It is rather striking, in this context, that the two best-loved police dramas of recent years, Line of Duty and Happy Valley, both feature tough, no-nonsense police officers of the old school, with an absolute, unmitigated focus on preventing crime. (“There’s only one thing I’m interested in,” goes the catchphrase of Line of Duty’s Ted Hastings, “and that’s catching bent coppers.”) Both are also impatient with officialdom, which they treat as a tedious obstacle to their real work; and both are very definitely un-woke.

In the last series of Happy Valley, its hero, Catherine Cawood, is reported by another officer for “bullying and racism,” a claim she treats with contemptuous outrage. Probably the allegation is indeed unfair—but the point is that she shrugs it off in a way that would be impossible for any remotely ambitious police officer. The popularity of these shows, among the viewing public and the Guardian-reading classes alike, hints at a profound national anxiety. On some level, the British people realize that the old, vocational ideal of the police is going, going; and its replacement will be less human, more bureaucratic, more likely to knock on your door and demand that you explain your political opinions down at the station.

What is often characterized as a crisis of free speech, then, goes deeper: It is also a widespread crisis of democracy and of identity. Some day, some historian will have to tell us how British institutions reached such a point of existential confusion, how they became sufficiently empty of ideals, that they could be captured by official ideologies so unworthy of a great nation.