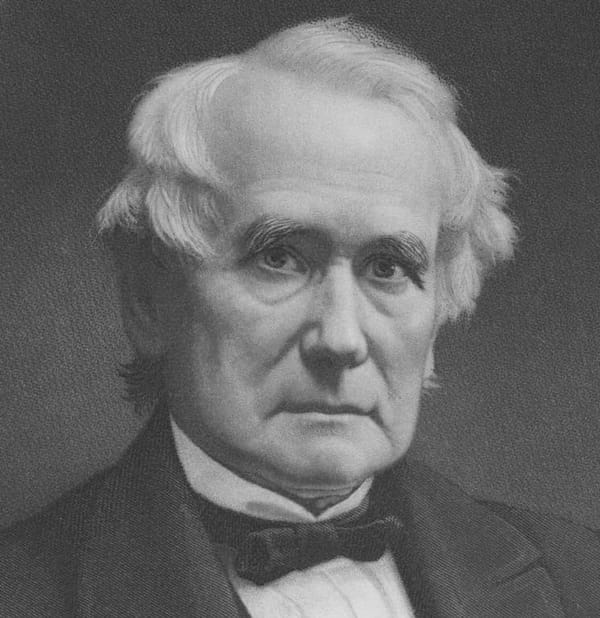

President Donald Trump’s revival of trade protectionism should also prompt renewed interest in the ideas of Henry Charles Carey (1793-1879), arguably the most influential economist in American history. One might conclude from the horrified reactions to Trump’s various tariff proposals that free trade has always been the American way, if not a principle enshrined somewhere in the Constitution itself. In reality, for most of American history, particularly between the Civil War and World War II, the nation’s industrial economy exploded to global supremacy under an elaborate system of protective tariffs. Carey was early America’s ablest and most celebrated proponent of economic nationalism.

Feted and honored by his contemporary admirers as an intellectual giant, Carey was also the first American economist to gain a significant audience in Europe. Karl Marx considered Carey “the only American economist of importance.” And John Stuart Mill paid him an equally backhanded compliment as “the only writer of any reputation as a political economist, who now adheres to the Protectionist doctrine.”

Mill was not exaggerating the low repute of protectionism in the 19th century. Among academics and intellectuals in America and Britain, free traders had won an overwhelming victory over their protectionist counterparts. But a doctrine fashionable academics have universally rejected does not, on that account, vanish from the face of the earth. Carey’s ideas gained an immense following among politicians and businessmen even as academics continued to pronounce them discredited and dead.

Carey’s father, Mathew, was an Irish Catholic who immigrated to Pennsylvania in 1784 and established one of the nation’s most successful publishing firms. Carey was educated entirely by his intellectually formidable father (an experience he shared with Mill). He went to work for the family firm when he was nine; became a partner at 22. In 1835, at age 42, he retired from the publishing business and devoted himself to the study of economics. The animating theme of his work, developed in a prodigious output of articles, essays and books, was his commitment to economic nationalism, his belief that economic principles were rooted in the nation’s distinctive circumstances and destiny.

“Carey considered himself a true disciple of Adam Smith.”

Carey considered himself a true disciple of Adam Smith, and he never endorsed the mercantilist premises that Smith had famously attacked—the idea that national wealth can only be increased through a positive trade balance, that is, by maximizing exports and minimizing imports. Carey fully embraced Smith’s insight into the productivity gains created by the division of labor. Yet he resisted the conclusion that seemed to follow when applying Smith’s insight to international trade: Protective tariffs artificially divert capital and labor away from the productive efforts in which the nation enjoys a comparative advantage to pursuits that are inevitably less efficient. Trade between nations, in this account, enriches both in precisely the same way that trade between a butcher and baker benefits both.

Carey, by contrast, sharply distinguished between internal “commerce” and external “trade” as fundamentally different social phenomena. “Commerce” within a community is almost always salutary, an extension of the associations and collaborations that are essential to all human flourishing. But “trade” between separate communities, particularly communities with drastically different economic, legal, and cultural institutions, is usually predatory and exploitative. Carey pointed to the slave trade and the Opium Wars as emblematic examples of external trade’s predatory nature.

The 19th century is rife with glaring illustrations of how different trade between societies at different levels of economic diversification and specialization looks from commerce within those same societies. Carey’s basic insight is that economic principles are not as timeless or immutable as the laws of physics. They are historical, which is to say they develop organically with the society in which they operate. The phrase “Indian giver” is itself a relic of the fact that Native Americans and Europeans did not understand trade exchanges in the same way. The inevitable result was misunderstanding and violence.

The key concept in Carey’s analysis was “association.” By association he meant the fruitful combination that results from the division of labor and the union of men. “The tendency of man is to combine his exertions with those of his fellow men,” Carey wrote. But these exertions are not exclusively commercial or material. They are cultural, political, intellectual, and moral—a collective striving from scarcity, savagery, and ignorance toward plenty, decency, and enlightenment.

The crucial point for Carey is that commercial networks are not separate from the other social bonds that create a community. People who belong to the same culture, obey the same laws, and rely on one another for their common defense should also be able to provide one another with all the material necessities of life. These bonds are mutually reinforcing. Interdependence is the glue of community. A heavy reliance on external trade corrodes the internal social harmony on which progress depends.

The more a society engages in external trade, the more specialized its own internal economy will become. But economic specialization, divorced from the broader associations that bind a community together, is neither safe nor fruitful. In a Hobbesian war of all against all, no individual can afford to specialize and rely on trade for the other basic necessities of life. And the same is true of individual nations in a Hobbesian world of predatory states.

The more important point, for Carey, is that national specialization diminishes the internal diversification that drives economic progress in the first place. Everyone in society is improved by close collaboration and interaction with near neighbors engaged in different pursuits and cultivating different individual capacities. The material benefits, in terms of economic efficiency, are only a part of the moral, political, and cultural advantages that flow from increasingly complex forms of interdependence and association. These advantages are mostly lost in trade exchanges with people on the other side of the world who have nothing else in common. A nation advances in every sense as its internal economy diversifies, as the reciprocal pursuits of its citizens multiply. External trade, by separating economic interdependence from all other forms of association, reverses this process. The nation’s internal economy becomes less diverse; citizens become isolated in a stultifying uniformity. The more concentrated a nation’s economy is, the more internally stunted and externally vulnerable it becomes.

“In all communities in which the power of association is growing, because of increasing diversification of employments, and increased development of individuality, we witness a constant increase of strength and power,” Carey wrote. “Steadiness diminishes with the increased necessity for trade; and therefore is it that in all communities in which employments have become less diversified; there has been a constant decline of both strength and power.”

Productivity, economic diversity and social cohesion all increase together in a virtuous cycle, and the wealth of the community expands with the variety of talents, intelligences and virtues of the individuals who compose it. As labor becomes more and more productive, Carey wrote, man “will learn more and more to unite with his fellow man, and will acquire daily increasing power over the land and over himself: and he will become richer and happier, more virtuous, more intelligent and more free.”

Carey’s theory of commerce and trade obviously strayed far from the narrow confines of modern economics, into fields now reserved for moralists, historians, political theorists, and sociologists. His outlook was embedded in a distinctly American political philosophy—one Carey learned from reading Alexis de Tocqueville. Americans, Tocqueville wrote, had “most perfected the art” of associating together. This was as much an economic as a political process.

“Raiding and trading were usually combined as twin facets of the same enterprise.”

The opposite of association is appropriation, which Carey defined as profiting by the exercise of power over others. The history of the world, he noted, is the history of armed, organized bandits, often calling themselves a government or empire, impeding the natural progress of association by appropriation. Carey made the historically valid observation that raiding and trading were usually combined as twin facets of the same enterprise. Pirate-traders switched opportunistically between the two roles depending on what seemed most advantageous under local circumstances (The Vikings were a stark example of this, but it was also true of the conduct of Britain and other Western empires in the 19th century). It is only when a territory comes under the control of a predominant power that trade becomes reliably peaceful. But the peace imposed created centralized order at the expense of natural association.

The United States, Carey believed, offered the most promising possible escape from this grim history. In overthrowing the political bonds with Britain, America had taken a crucial first step in its great destiny. But it would be for nothing if America did not break its economic dependency on the mother country.

“The whole legislation of Great Britain,” Carey wrote, had been directed “to the one great object” of making itself the workshop of the world and preventing any other nation from challenging its industrial preeminence. Britain forced its colonies to export raw commodities and then repurchase them as manufactured goods at artificially high prices.

Even if this had been true in America’s colonial past, Carey’s critics pointed out, it obviously was not true after the United States won its independence. Americans bought foreign goods and sold their own produce abroad only to the extent that they themselves believed it was in their interest to do so. The trade pattern between the two countries reflected the basic fact that land was relatively cheap and labor scarce in America. Why should the government use tariffs to “protect” the people from their own freely chosen preferences in a competitive marketplace?

Carey’s answer to this objection will seem familiar to anyone who has followed debates over affirmative action. Protection was temporarily necessary to overcome the results of Britain’s inequitable policies toward America in the past.

At the same time, Carey valued economic diversity, and the incalculable social, intellectual and material benefits that flowed from it, as an end in itself, one that trumped his commitment to unfettered competition. The nationalist creed that informed his commitment to protectionism endures in the motto of affirmative-action proponents, “Our diversity is our strength.” Carey’s protectionist philosophy also contained the same ominous ambiguity evident in affirmative action rationalizations—an expressly temporary system of preferences that might persist indefinitely. Economic sectors originally protected because they were too disadvantaged to compete on equal terms gradually and imperceptibly became political constituencies that were too powerful to be overthrown.

But the contrast between Carey’s economic diversity and our own commitments is equally striking. Today’s conception of diversity includes an ever-expanding number of identity categories, whose members demand inclusion and representation. But economic diversity—that is, diversity rooted in different productive pursuits, is relatively unimportant, if not completely irrelevant, to this sacred concept.

Today’s economic consensus inverts Carey’s distinction between internal commerce and external trade. We are now hypervigilant about basic power disparities within the workplace that cannot be resolved by the free association between capital and labor. A vast regulatory system now governs and restrains commercial relationships domestically. Employers can be punished, and punished severely, for failing to ensure their employees’ welfare as provided by a bewildering variety of regulatory and legal standards. Nineteenth century free traders denounced tariffs and workplace safety laws alike as artificial restraints on trade. Today, it is primarily in the sphere of international trade that one finds the most strident insistence on laissez-faire principles. Many economists who attack remaining international trade restraints with the boldness of a lion become as meek as a lamb in resisting the familiar embrace of the domestic nanny state. And for good reason: To claim that free trade between democracies and dictatorships will enrich and liberalize both is to repeat a harmless and familiar cliché. To claim that market incentives alone should determine whether domestic employers provide maternity leave or discriminate against racial minorities is to invite outrage.

“Economic nationalists are enjoying a roaring comeback.”

When a country governed by strict labor laws trades with another nation governed by weak or nonexistent labor laws, the result is bound to be economically and socially distorting. The legal disparity reverses the natural economic and social forces that favor commercial relationships between near neighbors and fellow citizens. Now consumers in one country actively prefer distant producers precisely because those producers are far removed from their own laws. Trade between the two countries thus becomes more attractive and pervasive than it otherwise would be. The two countries’ internal legal regimes may evolve even further to reflect this artificial comparative advantage.

For Carey, the influence created by this trade relationship is a perversion of the natural associational bonds in which commerce is embedded. Instead of binding people together more closely in a shared system of law, morality and culture, trade escalates external rivalries and mutual jealousies. It pushes a society away from internal self-sufficiency and toward external dependency. Reliance on external trade makes a society’s economy more and more dependent as it becomes more and more specialized. The more a nation’s vital interests exist outside its own borders, the more that nation will face a choice between being a bully and being a patsy.

Carey also believed that having a variety of employments within one’s own country was important for the full flourishing of citizens with naturally differing abilities. An economy focused on only certain industries is going to reward the aptitudes and talents of some citizens while leaving others to languish. Most people must find work within their own cultural, linguistic and political boundaries, even if they rely on international trade to supply their needs. A society that offshores its manufacturing base does not offshore those citizens most suited to thrive within that sector of the economy. It merely abandons them. A society that relies too much on external trade provides for its citizens’ varied needs as consumers but neglects their equally varied aptitudes as workers.

Trade relationships that push a nation’s internal economy toward greater concentration may be temporarily lucrative and still have insidious effects on its long-term growth, social structure, and political stability.

Economists now recognize this basic pattern in what is known as the “resource curse”—that is, countries rich in resources often have terrible developmental outcomes. The underlying causes of this pattern are debatable. And it is obvious that an abundance of natural resources does not necessarily doom a nation to poverty. The resource curse is most apparent when a very poor, underdeveloped society finds itself in possession of a natural commodity that very rich, technologically advanced societies consider valuable. The sudden interest in this hitherto neglected part of the world is bound to be experienced as a social calamity by those on the receiving end of it, even if a select few of them become spectacularly rich in the process.

Carey anticipated this phenomenon in his distinction between commerce and trade. He noticed that the more advanced economies tended to distort and retard the internal development of less advanced economies. But it seems that a mirror image of this dynamic has emerged among advanced Western economies in more recent decades. As Nicholas Eberstadt has shown, the percentage of prime age males in the United States who are neither employed nor looking for work has clicked steadily upwards, from around 2 percent in 1950 to 12 percent in 2016. The relentless consistency of this trend—ever-upward at the same gradual pace—is as striking as its invisibility. Eberstadt describes it as a “quiet catastrophe.” That combination is also what makes the trend particularly concerning. It suggests that American society is becoming increasingly alienated from the economic contributions of its own members.

Political divisions in all Western societies now reflect an internal conflict between economic sectors that have benefited from globalization and those that have been decimated by it. “People used to think of the economy as congruent with society—it was the earning-and-spending aspect of the nation just living its life,” Christopher Caldwell has observed. This way of thinking has begun to vanish among elites, even as voters have continued to insist upon it. The increasingly shrill divergence between a nation’s elite and its voters reflects a growing tension between how the world is organized politically and how it operates economically.

The ultimate outcome of this conflict is anyone’s guess. Perhaps in the long sweep of history, the nation-state will appear as a brief anomaly. Perhaps more layered and overlapping political communities will reemerge to replace the system of territorially sovereign states that first began to emerge about 400 years ago.

But in America in 2025, it seems reasonably clear that economic nationalists are enjoying a roaring comeback. As one of the first to develop this mindset, along with the assumptions, insights, and aspirations that make it appealing, Henry Carey deserves a victory lap.