If you had a baby in the new year, congratulations—you’ve given birth to a new generation. According to the Australian research consultancy McCrindle, as of January 2025, babies will no longer be “Gen Alpha” but, somewhat underwhelmingly, “Gen Beta.” Apparently, they’ll be a lot like the “Alphas,” born between 2010 and 2024, but shaped even more by new technologies. Quite the seismic shift. Eschewing hazier designations like “Millennial,” McCrindle explains that naming generations “is best done scientifically, using letters”—as though arbitrarily parsing society out into 15-year blobs is anything but marketing mythology.

The Beta label has little to do with science and everything to do with piggybacking on previous branding success: It was McCrindle that coined the “Alpha” generation label, and now the company wants to cash in on the sequel. Even as branding, “Beta” fails miserably. As one news report noted, it “sounds like an insult,” along the lines of “beta male.” But the real danger is not that these labels are silly. It’s that they are actively distorting our understanding of the world.

Generational labels have fueled a decades-long blame game that twists real economic, political, and social problems into simplistic morality plays. In the first two decades of the 21st century, this mainly took the form of a narrative in which self-interested Baby Boomers had stolen the future from their Millennial children. This sort of generationalist claims-making seeks to reimagine today’s social, economic, political, and cultural problems as though they are the fault of people who had the temerity to be alive in more dynamic and optimistic times. This notion has encouraged sentiments of grievance among the young while absolving policymakers of responsibility for the problems of today.

The cult of Boomer-blaming has its roots in demographic anxieties about aging populations and a worsening “age-dependency ratio,” in which a relatively small number of working people end up supporting a relatively large number of pensioners who, thanks to improvements in living standards and healthcare, live for many years. These fears led to calls, largely from those on the political right, to reduce welfare spending on the elderly in the name of “intergenerational equity.” This reached a fever pitch around 2010, as the Baby Boomers began to draw their pensions.

The ageism of this “grandma-mugging” approach to policy was given progressive cover by a cultural narrative that positioned the Baby Boomers as a powerful bloc of regressive interests, on a mission to thwart the superior values of the (then) young Millennial generation, which was described in a 2018 report for the Brookings Institution as “a demographic bridge to America’s future.” Organizations promoting the mission of “intergenerational equity” boasted that this was a claim that transcended the political divide—we could all agree that “the future” required demanding reparations from the old to the young.

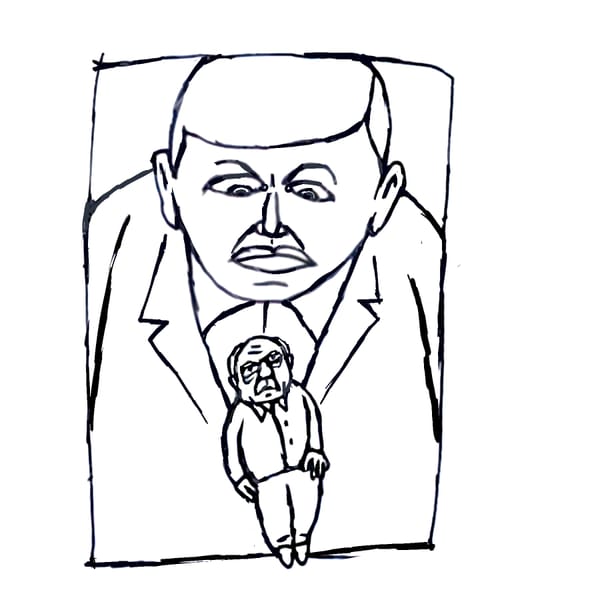

These claims weren’t just misleading; they were hugely corrosive. They turned political and economic grievance into personal vendettas, placing the blame on living people: your mother, your grandfather, yourself. It became so extreme that American venture capitalist Bruce Cannon Gibney published a book slamming Boomers as “a generation of sociopaths.” While absurd, this framing has proven enduringly popular.

“The excesses of generationalist claims-making may be waning.”

Thankfully, there are signs that the excesses of generationalist claims-making may be waning. In 2021, a group of demographers and social scientists wrote to the Pew Research Center, which has been at the forefront of generational research, criticizing the divisiveness and pseudoscience of the standard labels. Pew acknowledged that the field “has been flooded with content that’s often sold as research but is more like clickbait or marketing mythology,” and announced that it would take a new approach to the subject going forward.

Cracks in the Boomer-blaming narrative also began to appear when forecasts showed that the Millennial generation is set to become “the wealthiest in history.” The assumption that the young are inherently foot soldiers for progressive politics also took a hit when right-populist politicians and parties in the US and Europe began picking up larger shares of the youth vote.

But we shouldn’t declare the “generation wars” over just yet. These wars were always stoked more by political and cultural elites than the public at large. And when it comes to elites, the demographic and cultural anxieties that led them to point the finger at Boomers in the first place haven’t gone away. They are just taking new forms.

In recent years, concerns about an aging population have been manifesting in a panic about falling birthrates, which often attributes the problem to young people’s failure to have enough children soon enough. Proposed solutions have ranged from abortion restrictions to support for more affordable childcare, but the debate rarely engages with deeper cultural reasons why young people might feel unwilling or unable to embark on having children—an endeavor that not only requires confidence about the future, but also a desire to forge continuity with the past.

In her recent study of generational differences, US psychologist Jean Twenge reports survey data showing that 4 out of 10 members of Gen Z (in her definition, those born 1995-2012) believe that the founders of the United States are “better described as villains” than “as heroes.” This is in marked contrast with the sentiments of the older Boomer and Silent generations. Members of Gen Z are also less likely to believe that “America is a fair society where everyone can get ahead.” As Twenge observes, these young adults’ pessimism about their personal futures cannot be explained away by the considerable economic and political difficulties confronting them right now; they are negative “not just about the current world” but about a time 250 years ago.

One legacy of Boomer-blaming is that younger generations have been socialized into the idea that the people who lived in the past are the cause of all problems today. This estranges them not only from their elders, but also from their own futures. If we want our societies to move forward and reproduce themselves, a starting point is to challenge divisive narratives that present the young as the solution to the problem of the old. We must focus on how different generations support each other in the project of making a good life. We need to find ways of promoting a more measured understanding of our shared history, and a more open and positive orientation toward the decades to come.